Let’s focus on the future, which is in our power to shape, not on the past, which can’t be changed, writes David Kilgour.

Let’s focus on the future, which is in our power to shape, not on the past, which can’t be changed, writes David Kilgour.

By David Kilgour, September 2, 2020

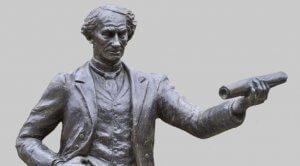

John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister in 1867, was born in Glasgow, Scotland and emigrated to Kingston, Upper Canada in 1820. At the age of 15, he began training in law, ultimately combining it with business interests, primarily land development.

He served as prime minister for 19 years between 1860 and 1891 and has been widely touted as a nation builder – the Father of Confederation – a leader in achieving a parliamentary government for the United Kingdom’s then North American colonies.

However, his complex legacy had a darker side.

As architect of the much-criticized Indian Act, Macdonald’s government also initiated the residential school system which, for more than a century, forcibly removed at least 150,000 Indigenous children from their homes and sent them to government-funded boarding schools. Many were abused; some died. They were forbidden to speak their own languages or practice their cultures. A government report in 2015 called it “cultural genocide.”

Determined to connect Canada from coast-to-coast with a transcontinental railway, the national government also forced some First Nations from their traditional territories, withholding food until they moved to areas designated as reserves.

Macdonald was also the arch-enemy of Louis Riel, founder of Manitoba, member of the Parliament of Canada, outlaw, exile, and ultimately executed in 1885 –despite being seriously ill at the time of his death of the hangman in Regina for high treason after the Métis rebellion. Macdonald, deciding that he could better afford to lose seats in Québec than to have English Canada turn against him, spitefully remarked at the time, “(Riel) shall hang though every dog in Québec bark in his favour.”

The gross insensitivity of the Macdonald government was clearly the major cause of the tragic last stand of the Métis people. Unsurprisingly, the Canadian Pacific Railway’s transcontinental line was completed nine days before Riel’s execution.

Recently, activists in Montréal toppled a statue of Macdonald, calling him “a white supremacist who orchestrated the genocide of Indigenous peoples with the creation of the brutal residential schools system.”

The activists said that they’d petitioned Mayor Valérie Plante to remove the statue. However, due to “inaction,” they decided to take matters into their own hands. As perpetrators, they should be charged with vandalism.

Around the world, a number of statues of controversial historical leaders have been toppled during heated public debates over how societies should remember leaders associated with slavery, empires and racism.

In the United States, statues of Christopher Columbus and Confederate leaders have been removed; in the UK, monuments to prominent slave traders have been taken down.

Belgian protesters defaced statues of King Leopold II due to the inhuman legacy of his personal colony in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Macdonald’s legacy and how he should be remembered is part of an ongoing debate in Canada.

One statue of him was removed from city hall in Victoria, as a gesture towards reconciliation with Canada’s Indigenous people. The Canadian Historical Association has removed Macdonald’s name from one of their prizes.

The debate at least echoes the United States movement to remove Confederate symbols from the American Civil War. However, a central difference is that the Confederate statues commemorated enemies of the United States – those who tried to secede from the Union, had committed treason in so doing, and were only defeated in a bloody civil war – compared to Macdonald’s legacy of being an undisputed founder of the nation.

Although history can’t be erased, activists and others feel that Macdonald’s name should be removed from federal properties and that his statue in Montréal shouldn’t be restored.

Even in the United Kingdom, the Scottish National Party-led government has disowned Macdonald by scrubbing him – at least temporarily – from government websites and from Scotland.org sites, saying that it’s “following the legitimate concerns raised by Canadian indigenous communities about [Macdonald’s] legacy. While we want to celebrate the very positive contributions Scottish people have made [globally], we also want to present a balanced assessment of their role.”

Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, reminds us however that South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission called for “a need for understanding but not for vengeance, a need for reparation but not for retaliation, a need for [kindness] but not for victimization.”

Let’s focus on the future, which is in our power to shape, not on the past, which can’t be changed. We must seek to undo the need for vengeance as a means of addressing past wrongs.

David Kilgour is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the former secretary of state for Asia Pacific.