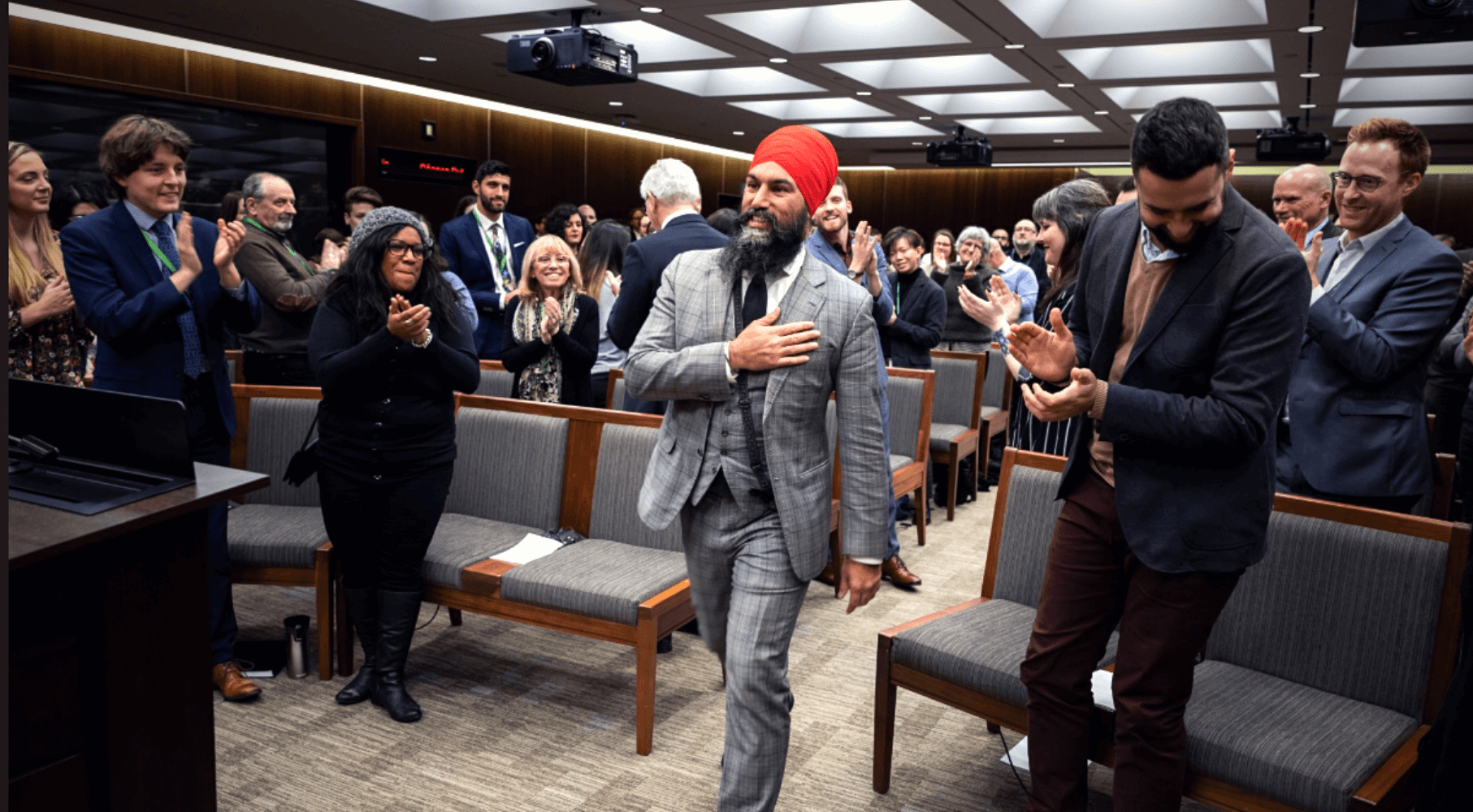

NDP leader Jagmeet Singh’s recent remarks show the need to adopt factual and reasonable language when engaging on issues related to the duty to consult, writes Joseph Quesnel.

NDP leader Jagmeet Singh’s recent remarks show the need to adopt factual and reasonable language when engaging on issues related to the duty to consult, writes Joseph Quesnel.

By Joseph Quesnel, January 28, 2019

Recent comments by the leader of the federal New Democratic Party (NDP) suggest that the party needs to adopt reasonable and legally sound positions on issues related to the legal duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous communities when development activities affect their traditional territories.

The NDP is not alone; politicians of all parties have been responsible for mixed or wrong messages on duty to consult.

In his recent remarks about the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion during an interview with CBC’s The National, Jagmeet Singh appeared to conflate the legal duty to consult and accommodate Indigenous communities with obtaining unanimous consent among those affected communities. It’s especially notable since it’s coming from the head of a major federal party that aspires to government.

In fairness to Singh, his actual words were: “They can’t say that they want to build something and say it’s going to be built, and then on the other side say, ‘We’re going to meaningfully consult with communities.’ That is not meaningful consultation if you’ve already decided the outcome.”

While it is true that the duty to consult means that you have to listen to Indigenous people before you make up your mind, the problem with this statement is that it seems to pre-suppose that the legal duty to consult is about obtaining a clear head count on which First Nations are opposed and which are for. Instead, it involves more about finding out if a First Nation’s rights and title are affected and perhaps negatively impacted by certain resource activities and finding ways to reach out to that community to mitigate those impacts.

As judges at the highest levels have stated and many commentators echo, the duty to consult and accommodate does not mean obtaining unanimous or even majority consent. Without getting too technical, there may be times where the duty may lead to a veto, but there is a very high legal threshold for that. Suffice to say, there is no free-standing legal requirement of consent for First Nation communities in our legal system.

Singh, however, to his credit, did recognize a problem inherent in consultations between industry proponents and affected First Nations. In the same interview he said: “Well, we’ve got to be committed to doing more than just checking off a box… That’s not enough. That’s not actually going to be reconciliation. If you just go say, ‘Well look, I’ve done this, and I’ve done this I’ve checked off a box’ … that’s not meaningful reconciliation.”

He is right, that is generally not a good way to conduct meaningful consultation with the First Nation side. The legal duty to consult involves an obligation on resource proponents to engage in good faith negotiations with First Nations. In a nut shell, the duty to consult gives First Nations the right to be heard in a meaningful way and for any of their concerns to be dealt with in good faith. And, if they choose to proceed with development, you have to respect the opinions and choices of the Indigenous side.

Thomas Issac – a nationally-recognized authority on Aboriginal law and consultant to governments in the area – wrote that the accommodation part of the legal duty directs that governments adjust, adapt, and compromise in the face of infringements of Aboriginal and treaty rights involved in the resource development activity in question. So, the entire duty to consult framework can be seen to favour the Indigenous side in the relationship, although it is also clear that First Nations have a duty to not frustrate the consultation process.

The problem with the duty to consult issue is that many have conflated and confused our made-in-Canada constitutional requirements on consultations with aspirational political rhetoric surrounding the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The Truth and Reconciliation Commission report complicated matters by calling for implementation of UNDRIP priorities in many areas of common life. Also, a private member’s bill by an Indigenous NDP MP that calls for Canada’s laws to be in harmony with UNDRIP is sailing through the legislative process.

This non-binding UN declaration was endorsed by Canada in 2010 under the Conservatives, albeit with caveats surrounding certain sections that dealt with land and resources and obtaining consent from Indigenous peoples in Canada before passing laws. The so-called Free, Prior, and Informed Consent aspect – called FPIC by observers – is the most problematic for resource development relationship involving industry and First Nations.

In 2017, the Liberal government removed its “objector status” to UNDRIP. A year prior, Indigenous Affairs Minister Carolyn Bennett – to literal applause at the UN – said that the new Liberal government intended to fully support the declaration without qualification. And then promptly added, “We intend nothing less than to adopt and implement the declaration in accordance with the Canadian Constitution.”

Did she miss that the obvious point that our constitutional system would qualify UNDRIP’s provision and their applicability to Canada, especially where they come into conflict?

Since then, the federal government has been more temperate and guarded in speaking about UNDRIP and its applicability in Canada. One could argue that the Liberal government quickly realized when they formed the government the practical implications of UNDRIP. It could be said that in their attempt to govern and put their imprint on policy, the Liberals had to jettison this bold and arguably quite radical claim, since they governed for all Canadians and not just First Nation communities involved in resource projects.

A very literal reading of the FPIC provision would be very destabilizing in terms of resource development relationships in Canada, as it would provide the Indigenous side with too much power. The legally sound duty to consult is about balancing of rights and interests, not granting one side too much sway.

Some legal commentators have argued already that the existing duty to consult and accommodate process already allows in many cases the power for First Nations to, at a minimum, delay, and at a maximum, scuttle projects by dragging the process out so long that proponents and investors lose resources and patience with the project itself. Enshrining a literal FPIC legal requirement would tip these already loaded scales to one side.

Again, the problem is Indigenous leaders and activists who make statements on the duty to consult that combine factually-correct legal statements and highly questionable aspirational political rhetoric. The problem is many Canadians – including politicians and average First Nations people – parrot these talking points as if they were true when they are not.

Perhaps Singh – like Prime Minister Trudeau and Minister Bennett before him – would toss aside these radical interpretations if the NDP ever won enough seats to form government. One would hope. However, it makes sense for their party to adopt a reasonable and legally sound position now for Canadians to take them seriously. Indeed, Singh should do so as quickly as possible if he wants to convince Canadian voters – especially centrist swing voters looking for a reasonable alternative to the Liberals – that their party is ready for prime time.

A look at the NDP’s current policy book shows that the party itself adopts a more robust interpretation of UNDRIP provisions. In one part the book reads: “Ensuring that all trade agreements are consistent with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and before agreeing to any trade agreement or provisions that could affect Indigenous peoples, the government obtaining their unqualified, free, prior and informed consent.”

“Unqualified,” as mentioned above, is very bold and quite radical language that would be massively destabilizing in terms of granting Indigenous parties the power to hold up development activity, that is quite arguably in the national interest of all Canadians.

First Nations on the ground and informed resource proponents would know the difference between the more realistic and balanced duty to consult duty and the wild UNDRIP-inspired rhetoric of First Nation and non-Indigenous opponents of development. The NDP – and all federal parties – need to adopt factual and reasonable language when engaging on these issues. Singh is an example where that is not occurring and where politicians need to stand up for truth and reason. The timely development of resources that benefit all Canadians – especially remote and impoverished Indigenous peoples with few economic options – depends on it.

Joseph Quesnel is program manager for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Aboriginal Canada and the Natural Resource Economy project.