The federal government is pursuing an aggressive agenda using untried methods to regulate extremely low drug prices, writes Nigel Rawson.

The federal government is pursuing an aggressive agenda using untried methods to regulate extremely low drug prices, writes Nigel Rawson.

By Nigel Rawson, July 8, 2020

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB), the tribunal that sets ceiling prices for patented medicines in Canada, published its modified draft Guidelines on June 19th that are intended to allow the Board to put its new regulations into practice.

The revised Guidelines replace those released for consultation in November 2019 that produced more than 120 responses, of which at least 80 percent were negative. Respondents, including Canadian provincial cancer agencies, considered the earlier draft Guidelines to be too complex and that they would drastically cut drug prices, which would reduce patient access to new and existing drugs. A case study indicated that price reductions could be 45 to 75 percent, perhaps more, below existing levels. This would obviously deter developers from launching new medicines in Canada.

Doug Clark, executive director of the PMPRB, is reported in Hill Times Research as saying that the Board “believes it has come up with a revised set of Guidelines that genuinely and sincerely took the feedback it received into account.” Mr. Clark also doesn’t see any impact from the Guidelines on new drug launches in Canada and encourages “people to really look under the hood and see if they think we’ve got it wrong, because we don’t think so.”

What’s under the hood?

The PMPRB will maintain its narrow approach of assessing the therapeutic value of each medicine. In the last seven years, an average of 12 new medicines each year received a priority review or early approval from Health Canada as regulator of drug safety, effectiveness and production quality. However, an average of only two to three new medicines per year were categorized by the PMPRB as providing a breakthrough or significant therapeutic improvement.

Even if a new medicine offers much easier administration than an existing product, which improves adherence and persistency that lead to better health outcomes, the PMPRB will usually consider the two medicines to be equivalent. Classifying a medicine as having less benefit lowers the price ceiling.

The Guidelines will continue to allow the PMPRB to replace higher-price countries with lower-price countries in its international price comparison test. This will reduce the list prices of all currently-marketed and future patented medicines in Canada by about 20 percent.

The Board also persists in its intention to regulate prices using pharmacoeconomic methods to estimate a cost-effectiveness threshold representing the upper limit of the public health care system’s willingness-to-pay for new medicines. These methods, which were strongly criticized in responses to the earlier draft, are inappropriate for price regulation because they are based on data and methods that lack agreed standards and produce, at best, subjective and assumption-dependent estimates. They should not be used to determine prescriptive and legally enforceable price ceilings.

In addition, the Guidelines allow the PMPRB to restrict a developer’s profit by applying additional escalating price cuts on medicines using arbitrary market-size sales thresholds.

Although the thresholds for the pharmacoeconomic and market-size tests are now twice the ridiculous values originally proposed (likely to try to appease manufacturers), reductions based on these assessments will be applied on top of those resulting from the amended international price comparison test to calculate the maximum rebated price.

Evidence for a negative impact

Mr. Clark doesn’t present evidence for his opinion that the Guidelines will have no impact on new drug launches. Instead, he suggests that my previous analysis of new trials obtained from Health Canada’s clinical trials database was based on incomplete information because, he says, the database doesn’t include phase I trials and bioequivalence studies. This is a surprising comment because Health Canada’s website states that the database provides “information relating to phase I, II and III clinical trials.”

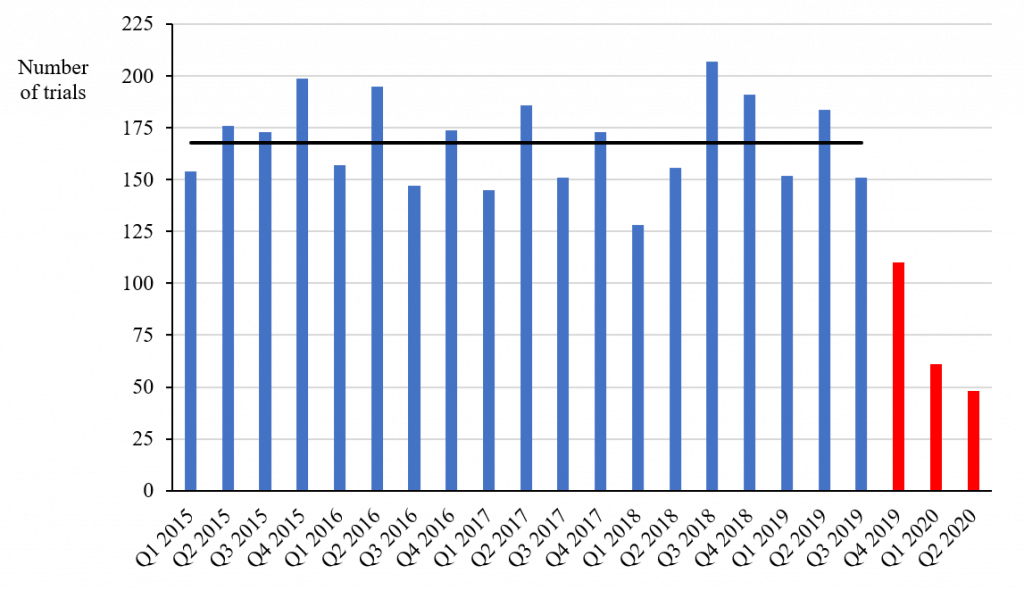

I used Health Canada’s database to compare the number of non-COVID-19-related trials with a “no objection letter” (i.e., approval) issued each quarter between 2015 and 2020 (see chart below). The average number of trials approved each quarter to the third quarter of 2019 was 168 – a figure consistent with Mr. Clark’s annual numbers up to 2019 (he didn’t report any numbers for 2020).

Non-COVID-19-Related Phase I, II and III Trials Approved between 2015 and 2020, by quarter

Source: Health Canada’s Clinical Trial Database

However, the numbers approved in the following three quarters were 110, 61 and 48, respectively, which are 66 percent, 36 percent and 29 percent of the average number in the previous 19 quarters. Since the decrease took place in the fourth quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020 before the lockdown due to COVID-19, the decrease is unlikely to be simply the result of the pandemic, although it may have accelerated the decline in the latest quarter. The numbers of non-COVID-19-related clinical trials approved in the first two quarters of 2020 are 64 percent and 71 percent below the average in the previous years – figures that even the PMPRB should find difficult to ignore.

Nevertheless, the PMPRB has so far disregarded other significant information that points to tight price regulation negatively impacting new drug launches. The first sign of concern about changes at the PMPRB came in 2017 when global pharmaceutical executives raised a red flag about them. In a more recent survey of Canadian and global executives, 100 percent of the respondents stated that the PMPRB revisions would negatively effect their overall business plans in Canada and almost all thought they would negatively impact product launches, commercialization and supply of current products to the Canadian market (97 percent), employment (97 percent) and clinical research (91 percent).

Analyses of the impact of price regulation leading to delayed drug access have been published since the early 2000s. The extensive work of Danzon and her colleagues has repeatedly demonstrated the relationship. The connection has been emphasized by a recent systematic literature review of 49 studies, of which 44 (90 percent) showed a significant negative relationship between price controls and investment in pharmaceutical research and development or access to innovative drugs.

The latest evidence comes from an analysis of the number of new medicines launched in the 25 countries with the largest pharmaceutical sales between 2000 and 2019 based on information provided by IQVIA, a large international company whose data are used by pharmaceutical companies, governments (including Canada’s) and the PMPRB. After adjusting for the two-year time lag due to new drug applications being submitted later in Canada than in larger markets, the number of new launches globally was consistent with those in Canada until 2019 when the number fell to just 13, about 42 percent of the 31 launched globally in 2017. Of 37 medicines launched globally in 2018, only 16 (43 percent) were launched in Canada.

Guidelines complexity and use

Rather than simplifying the latest version of the Guidelines, the PMPRB has amplified their complexity. They do, nonetheless, make it blatantly obvious that the focus of the PMPRB and the federal government is on new medicines with either a high cost or a potential market size that will significantly impact public drug plan budgets. The objective is to reduce prices for these medicines to rock-bottom or even lower.

It is also critical to recognize that the Guidelines are not a rulebook. As the PMPRB itself noted in a hearing relating to the price of Soliris in 2017, “the Guidelines are advisory only” and are “not binding on the Board.”

How will the PMPRB interpret the Guidelines – fairly, generously, arbitrarily, rigorously, punitively? Past experience suggests that they will not be applied generously.

When disagreements between manufacturers and the Board regarding prices lead to hearings, the company presents its case against PMPRB staff before members of the Board, not external judges. The PMPRB works for and is financially supported by the federal government and, as such, the Board has a conflict of duty.

Given the federal government’s aim to drastically reduce prices, the prospect is that the Guidelines will be used arbitrarily and unfavourably against drug developers.

Conclusion

The PMPRB and others in Ottawa believe in the fantasy that severely reducing prices will not impact manufacturers’ plans for bringing their new medicines, including vaccines, to Canada. I would be happy to see this belief turn out to be true. However, logic and many signals strongly indicate that the PMPRB revisions are already delaying and denying access to important new costly medicines that, in many cases, provide treatments for debilitating or lethal disorders that have previously been untreatable.

Many hurdles must be overcome before a new medicine is accessible through public drug plans. The PMPRB revisions will add a further barrier. The latest draft Guidelines are an even more complex mixture of formulae, price floors, price ceilings and missing information than the previous version. There is no way to properly calculate what a potential price could be in Canada. Consequently, drug developers don’t know what price they can legally sell their medicines for and, as a result, are avoiding the Canadian market.

What we see when we “look under the hood” is the federal government pursuing an aggressive agenda using untried methods to regulate extremely low prices, with no guarantee of funding or reimbursement even if a medicine is launched at the mandated low level. Canadians do not need a lemon (a vehicle that has numerous manufacturing defects affecting its utility or safety) that will cost them dearly down the road. We need a high-quality process that will allow both sensible prices and timely access to important innovative medicines.

Nigel Rawson is president of Eastlake Research Group and an affiliate scholar with the Canadian Health Policy Institute.