The pandemic has shone a revealing light on the disparity of rights and conditions for people who live in Indigenous communities, writes Melissa Mbarki in the Toronto Star.

The pandemic has shone a revealing light on the disparity of rights and conditions for people who live in Indigenous communities, writes Melissa Mbarki in the Toronto Star.

By Melissa Mbarki, January 21, 2022

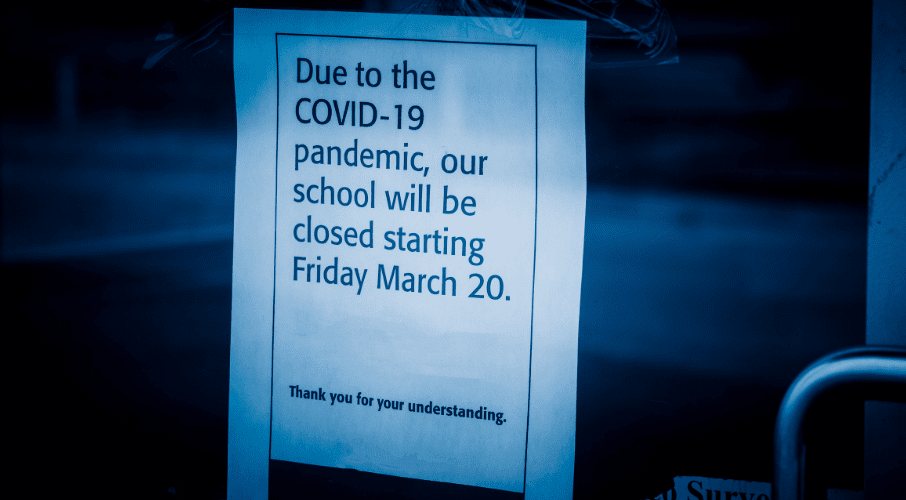

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a bad and difficult situation in Indigenous communities and made things much worse, often seriously so.

Indigenous children were already disadvantaged, even before the pandemic. Now, access to basic supports like reliable internet service and tablets or other learning devices remains scarce in many classrooms and households. As well, Indigenous schools continue to struggle to find teachers willing to live and teach in remote communities.

Add in the challenges brought on by the pandemic, and these issues become more difficult. Prolonged absences from school will leave Indigenous children further behind educationally — in a demographic where graduation rates already lag well behind national norms.

These problems alone represent a formidable obstacle to over come, but reserves also grapple with drug and alcohol addictions, poor health outcomes, family violence, high suicide rates and deep, multi-generational poverty. School is sometimes the only safe place, the only sanctuary these children have. For many children, school lunch programs provide one of the only meals they have every day, and these have been lost now for almost two years.

Growing up in Saskatchewan, we had “snow days” every winter. We loved these days off school, even though it meant my parents had to scramble to find a babysitter. I have four younger brothers and sisters, and in even normal times it was extremely difficult to find a day home or daycare in my area. In the pandemic, when parents are ordered to keep their kids at home, finding care is often impossible.

As for finding engagement beyond the classroom, few reserves offer many after-school or extracurricular activities for Indigenous children. Sports, music, dance, gymnastics, and art programs do not exist in many Indigenous communities. And if or when children fall behind, we do not have access to tutors.

In the end, the mental health of Indigenous children has been significantly impacted by school closures and the prolonged isolation of the pandemic. Many reserves do not have recreation centres or community buildings to hold youth group events. The dilemma is worse for children from homes with domestic violence and addiction issues, as this environment is now their full-time reality.

Even before the pandemic, suicide was the second leading cause of death among young adults aged 15-34. Far too often, we hear about suicides or attempted suicides in our communities. Sadly, this is a part of our lives. Now the situation appears to be getting worse.

When you combine the deadly threats of depression, isolation and lack of support services, you see with painful clarity that we have a mental health catastrophe on our hands. Where do we begin to address these issues? Outsiders tell us we should get help for these at-risk youth. As if that was possible!

Beyond psychological traumas, reports from northern communities indicate that children aged 5-19 now have the highest COVID infection rates on reserves. This is due in large part to chronically compromised sanitation and living conditions, including overcrowded homes and lack of clean water. It not yet known what the long-term health effects of COVID will be on children, but this is something that must be watched closely in the future.

How can Canada profess concern about the mental and physical health of Indigenous children if we will not address the litany of deplorable conditions on reserves?

The pandemic has shone a revealing light on the disparity of rights and conditions for people who live in Indigenous communities. Where do we go from here? Will many of these people even survive continued inaction? Almost all Canadians will agree that the answer is clearly no.

Canada must transform its approach to community services, Indigenous housing, mental health care and education if the country truly wants Indigenous people to be a part of, and share in, the nation’s prosperity and well-being.

Melissa Mbarki is a policy analyst and outreach co-ordinator for the Indigenous Policy Program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa. She grew up in Saskatchewan on the Muskowekwan First Nation, an hour and a half north of Regina.