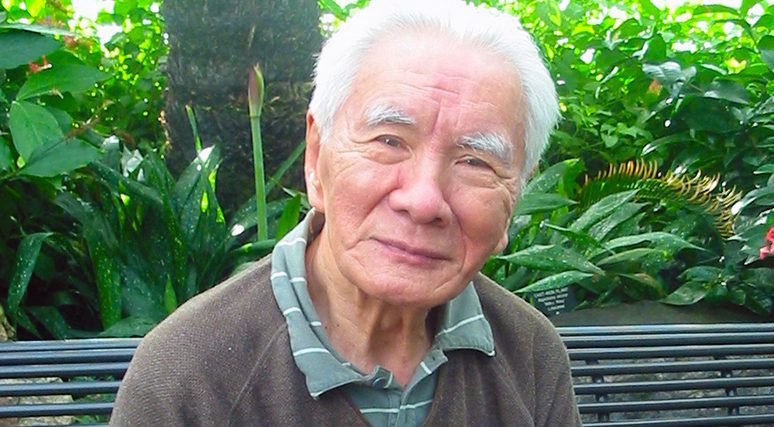

Writing in the Globe and Mail, Charles Burton and Diana Lary recount the life of Professor Jerome Ch’en.

Writing in the Globe and Mail, Charles Burton and Diana Lary recount the life of Professor Jerome Ch’en.

By Charles Burton and Diana Lary, July 10, 2019

Jerome Ch’en’s long life was shaped by the momentous historic events in China over the past century, and the insights he gained as a witness to those events informed his work as an eminent historian and author. Prof. Ch’en, who died last month, was one of the last survivors of a gifted generation of Chinese intellectuals who were born into a traditional society, came of age in warfare and either were exiled or remained in China to face persecution. They were steeped in both the Chinese and Western traditions. Prof. Ch’en’s deep knowledge of Chinese culture co-existed with his profound understanding of Western political and economic thought. He was equally fluent in Mandarin, Sichuan dialect and English.

Jerome Chih-jang Ch’en was born on Oct. 2, 1919, to a family in Chengdu that valued education. His father had passed the imperial public service examinations just before the system was abolished in 1905; the career that would have followed with the state bureaucracy also disappeared. His father scraped together an income to support his children, working as a secretary for a warlord, and he was successful in stock market investment. But when the market crashed in 1929, he went bankrupt. His wife died shortly after that. Years later, Prof. Ch’en wrote about her death in his unpublished memoirs: “One evening the sound of sobbing woke me up. Mummy had died. This was a time of terrible pain for all of us. My mother was a beautiful person. In death her face flushed red. The next morning her head was still hot.” That was the end of his family home.

Prof. Ch’en and his family (he was one of ten children, only six of whom survived to adulthood) were now homeless and destitute. He would not have a proper home again until the early 1950s.

Prof. Ch’en went to a missionary school where he learned English. In 1939, when he was ready for university, the Japanese invasion of north and east China had forced the flight of China’s great northern universities to the remote southwest. Prof. Ch’en went to Yunnan’s Southwest United University, in its time one of the finest universities in the world, made up of combined faculty and students of several displaced universities. It had no facilities; faculty and students were dirt poor, but the university graduated two future Nobel Prize winners and a host of other talented young people. Prof. Ch’en went on to teach economics at Yen-ch’ing University after the university returned to Beijing.

In 1946, he won a coveted Boxer Indemnity Scholarship to study in England, at the London School of Economics, under Friedrich von Hayek. When Prof. Von Hayek decamped from London to Chicago in 1950, Prof. Ch’en moved to London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, where he finished his PhD thesis.

By then the Communist Party had taken over China. Prof. Ch’en received a letter from his older brother warning him not to go home. For a young man from a bourgeois background with a degree in Western liberal economics, life could only be dangerous under Communist rule. He did not hear from his brother again for almost three decades. Throughout his exile, he remained strongly attached to Sichuan and his native province, and proud of the many celebrated Sichuanese, from the poet Du Fu to Deng Xiaoping.

Prof. Ch’en stayed in England and worked for the Chinese service of the British Broadcasting Corp.; he played for the BBC’s bridge team, but he was not considered suitable for promotion because he was Chinese.

He remade himself as a historian and got a job teaching at Leeds University. He also published the two well-regarded biographical works, Yuan Shih-k’ai(1961) and Mao and the Chinese Revolution (1965). These were not unhappy years, but there were no real prospects for him there. It was made clear to him that as an ethnic Chinese, he could not expect to get a chair in Chinese History.

In 1971, he was recruited to York University by the far-sighted historian Jack Saywell, who was then dean of arts. Prof. Ch’en spent many good years at York until his retirement. He wrote China and the West (1978), The Military-Gentry Coalition: China Under the Warlords (1979), State Economic Policies of the Ch’ing Government (1980) and The Highlanders of China (1992). He was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He was appreciated and honoured by his colleagues and students. Canada gave him the respect denied to him in China and in England.

Prof. Ch’en was able to return to China in the mid-1970s after a separation of three decades. He’d had no contact during the decades of China’s isolation from the West. His reunion with his family was profoundly emotional, but not without problems. His relatives had suffered for having a relative – him – in the West, and there were expectations that he would now help younger family members, financially or by sponsoring them to study abroad. He did his best, but there were too many nephews and nieces for him to help them all. Divisions within the family made it impossible for him to return to Chengdu permanently.

His separation from China was a source of deep sadness for him. In his youth, as an ardent patriot, he had been determined to serve his country and improve the living conditions of his people. He was denied the opportunity.

Prof. Ch’en became increasingly philosophical with age. In 2003 he wrote in a letter, “I do have a fear of death, because I love life. In spite of pains and sufferings, life remains the most treasurable and enjoyable above everything else.” His last years were spent at the Loyalist, a retirement home in St. Catharines.

He spent much of his time reading: “Books continue to be my silent friends,” he wrote in an e-mail to a friend. He read eclectically in English. In Chinese, he read the official biographies of Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and Mr. Xiaoping, and, as throughout his life, classical poetry. He hoped to emulate others of his generation by living past 100; the sociologist Chen Hansheng lived to 107, the writer Yang Jiang to 105. He made it, by Chinese custom, where a child is one at birth, but by Western custom he was a few months short. He died peacefully on June 17.

MLI Senior Fellow Charles Burton and Diana Lary are former students of Jerome Ch’en.