By Rory McDonell, March 18, 2022

Canada’s position as a northern nation has always been a source of pride. Immortalized in our national anthem, “the true north strong and free,” Canadians have viewed ourselves as both stewards and beneficiaries of the Arctic Circle. Climate change presents both new dangers and new opportunities, and Canada needs a more thoughtful policy that reflects the long-term potential offered by the Arctic. The federal government’s current policy touches on some important points, including sovereignty and Indigenous rights, but the vagueness of the plan leaves gaps in security and sovereignty in the region and does little to change our inability to exploit potential opportunities effectively.

The ever-increasing retreat of ancient ice exposes, by some estimates, 30 percent of the world’s untapped crude oil and up to 15 percent of the natural gas. These resources, and their potential to create enormous wealth, are balanced by the threat of natural and man-made disasters. In addition, countries like Russia and even China have begun to make claims to the region, which also need to be reflected in Canada’s Arctic security policy.

The Arctic Council, made up of eight Arctic nations and a number of Indigenous peoples, is an effective forum for dialogue and should be respected. The council has an important disclaimer to its mandate, however: it is not tasked to deal with matters related to military security. This amendment creates potential instability and Canada’s future position in the far north needs to be carefully considered in light of changing environmental realities, and the actions of state and non-state actors. Careful long-term planning will pay dividends for future generations.

The Arctic region is as inhospitable as it is mysterious. It is enormously difficult to reach, and even more difficult to study or understand. Some projections state that due to climate change, the ice caps will have retreated enough by 2030 to allow for more feasible navigation without the need for ice-breaking ships, particularly in the summer months. The shrinking ice has revealed both new shipping lanes and deposits of natural resources that were previously inaccessible. This potential wealth has created an international gold rush, made up of Arctic and “near-Arctic” states, looking to lay claim to the latent wealth hidden at the top of the globe.

Russia made its first claim to the land in 2001 and has taken an increasingly aggressive attitude towards the North, ramping up both its military presence and taking steps to quadruple shipping through the newly opened passages by 2025. This is not surprising given that Russia has a massive coastline protruding into the Arctic circle. Russia, more than any other nation on Earth, also stands to benefit from the changing opportunities brought about by global warming. Russia has proven to be an aggressive player on the world stage over the past two decades. Using both state, and non-state actors as a means to annex Crimea and assert influence over Eastern Ukraine and Syria, Russian President Vladimir Putin has been projecting Cold War-style power globally. This has culminated with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Today, the West is fighting a fierce proxy war in Ukraine, with weapons now being supplied to Ukrainian forces and unprecedented economic sanctions on Russia that threaten the very foundations of its economy. That has arguably made it imperative for Russia to appear strong and to secure resources for its own future. The possibility that Russia may attempt to exert sovereignty over foreign territories in the Arctic should not be discounted.

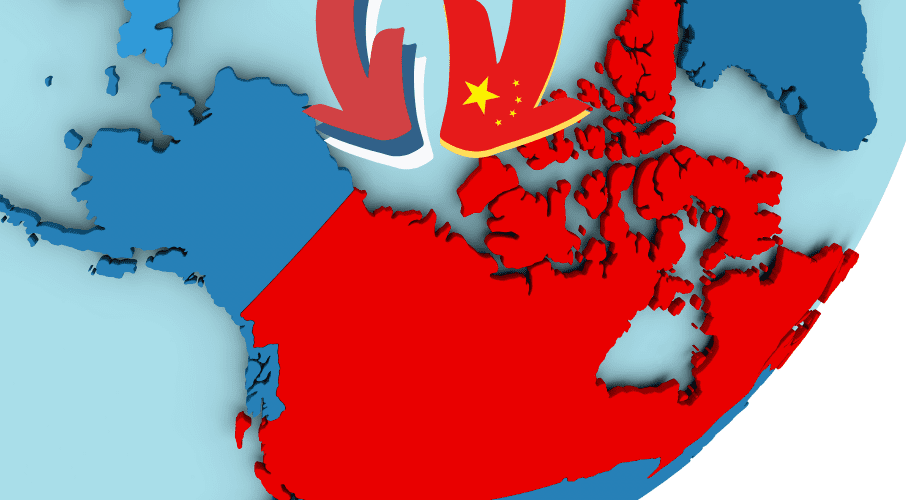

Perhaps more troubling in the long-term is how China, whose most northern tip is no closer to the pole than Berlin, has styled itself a “near-polar state.” In a recently published white paper, Beijing has made plain its intentions in the true north. The Polar Silk Road, as they refer to it, incorporates the northwest passage into the larger Belt and Road Initiative – a global infrastructure plan for much of Eurasia and a centrepiece of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s foreign policy. Given China’s propensity for manipulating the international Law of the Sea, as evidenced by their ongoing posturing in the South China Sea, this claim should make the true Arctic nations take pause.

What can Canada do to both secure potential resources, protect Canadian sovereignty, and defend against potential security threats?

Canada would also be well served to move away from the bureaucratic inefficiency surrounding innovation. Bolstering and supporting widespread innovation in the private sector, particularly in automated resource extraction, surveying and mapping, and deep-sea sub-ice imaging would potentially be enormously beneficial for Canada. This innovation should not be left solely in the hands of corporations, which have the financial means to undertake these expensive explorations but could lead to monopolies of corporate control. Instead, it should be subsidized at the grassroots level. Subsidies at the grassroots level would increase the intellectual capital available and would prevent the more egregious exploitation that can arise from monolithic corporate control.

The 2017 federal budget focused efforts and resources on the promotion of innovation, but to date Canada’s innovation performance has been relatively low compared to other similar economies. Canada’s poor performance can be arguably explained by a lack of coordination and policy alignment across and between multiple levels of government, which is particularly prevalent in the Arctic, and tenuous links between high-quality university research/design and commercialization.

In terms of actionable policy, the fact that Canada is the only Arctic nation that does not currently have an Arctic university should be troubling. Colleges can be found in each of the territories, but the lion’s share of funding and opportunities are funneled to universities in the south. In the same vein, there is no focused regional innovation policy in the Arctic and we have latent untapped human capital resources as well. The Arctic is a surprisingly robust “innovation environment” and harnessing the ingenuity of people who have survived for centuries in the world’s most inhospitable environment could produce valuable opportunities, while at the same time bolstering the self-determination of Indigenous peoples.

The growth of regional innovation in the Arctic could also positively impact the Canadian Armed Forces’ (CAF) role and presence in the extreme north. Currently, the acquisition of new technology and the replacement of deteriorating equipment is one of the weakest components of Canada’s security posture. By some estimates, it can take upwards of 15 years for new technology to be vetted and implemented in Canada’s military. Given the bellicose sabre-rattling from Russia and China and the potential for increased strategic competition among great powers, it is imperative that Canada looks for new means of staying abreast of military developments.

Canadian General Walter Natynczyk famously said that if anyone attempted an Arctic invasion, it would be his responsibility to go rescue them. The CAF’s role in search and rescue is unlikely to diminish over the coming decades. Quite the opposite in fact: as climate change increases, so too will natural disasters. Greater human activity in the Arctic also increases the potential for man-made disasters. Yet, given the return of great power politics, it is also imperative that the CAF increases its presence to combat hostile actors in the Arctic. Fully committing to a “dual role,” for both search and rescue and conventional defence, is no mean feat. Previous analysts have correctly identified the need for nuclear-powered submarines and more effective early warning systems in the Arctic, for example. Meshing this need with Arctic-focused innovations and growth could be an effective means of achieving such a posture.

Canada could also improve our relationship with the Americans by beefing up our military presence in the Arctic, as well as reinforcing our presence near the newly opened coastline facing Russia. This increased military presence would provide several benefits, from projecting our own sovereignty and guarding against malign state and non-state actors to having well-trained response teams to help manage potential man-made and natural disasters.

While some pundits spend untold amounts of time and discussion debating if climate change is happening or not, Russia and China are laying long-term plans for the coming shifts in temperature and the make-up of our world. Fostering dialogue with the other Arctic countries to reach a consensus is imperative, but at the same time, we must prepare for less ideal outcomes. Canada’s policy should reflect the reality of how the world is changing, and if we are not thoughtful in our forecast we will lose not just opportunities, but sovereignty and safety as well.

Rory McDonell is a security consultant and policy analyst. He is a regular contributor to Rise to Peace, a counterterrorism think tank, and is developing a counterterrorism education program for law enforcement agencies, including the FBI, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Homeland Security. Connect on Linkedin.