Canada has a role to play in the contested maritime domain of the South China Sea, writes Irfan Yar.

Canada has a role to play in the contested maritime domain of the South China Sea, writes Irfan Yar.

By Irfan Yar, April 9, 2019

Late last year, at a conference in Beijing, a senior Chinese military officer suggested that China should attack US naval warships if they entered Chinese territorial waters. This comes a few months after US sent two naval ships to the disputed South China Sea that alarmed China. The US is at loggerheads with its near peer-competitor (China), which uses the South China Sea (SCS) as a strategic backyard. Deeply concerned over the Chinese militarization of SCS, the US has stepped up its “Freedom of Navigation” (FON) operations in the Indo-Pacific.

What happens in the SCS has become a grave concern to the international community, yet Canada is virtually silent on this issue. The country seems to have no clear diplomatic and strategic policy towards this contested maritime domain. This article explains why and how Canada should engage itself in the South China Sea.

The dispute in a glance

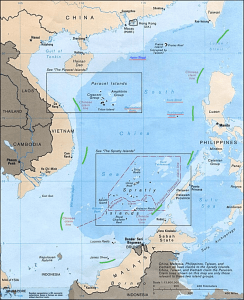

The South China Sea dispute arises from competing topographical and maritime claims made by Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Of these, China has by far the most expansive claim, asserting ownership of more than 80 percent of the sea on largely historical grounds through its so-called Nine-Dash-Line, which encompasses most of the South China Sea. The SCS carries enormous strategic importance; each year $3 trillion in annual trade flows through this route. Moreover, the SCS is home to both lucrative fisheries that are crucial for food security of East Asian nations and reportedly the site of significant underwater oil and gas reserves.

The South China Sea dispute arises from competing topographical and maritime claims made by Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Of these, China has by far the most expansive claim, asserting ownership of more than 80 percent of the sea on largely historical grounds through its so-called Nine-Dash-Line, which encompasses most of the South China Sea. The SCS carries enormous strategic importance; each year $3 trillion in annual trade flows through this route. Moreover, the SCS is home to both lucrative fisheries that are crucial for food security of East Asian nations and reportedly the site of significant underwater oil and gas reserves.

What are the current issues in the South China Sea?

Militarization: After pursuing an extensive land reclamation project to build artificial reefs and man-made islands in the SCS, China has begun to increase its military presence and infrastructure on these artificial outposts, including with runways, hangars, and radar sites. On two military outposts in the Spratly’s, for example, China installed radar jamming equipment that can disrupt radar and communication systems. In May 2018, China surprised many by also deploying anti-aircraft and surface-to -air missile systems in three of its outposts; this is the first instance that missiles of any kind were deployed to the Spratly Islands. In the northern Paracel islands, China has also deployed surface-to-air missile systems and there have been sightings of fighter aircraft and bombers using the facilities on Woody Island.

Violation of International law: China’s growing activities in the South China Sea are a clear breach of international law. In 2016, when the Philippines brought the matter to the Permanent Court of Arbitration, in the Hague, the court effectively rejected China’s entire legal basis for claims in the SCS, including its historical claim of waters within the Nine-Dash Line, its maritime claims over reefs and other features in the sea, and much of its activities in the SCS, most notably building man-made islands. In June 2018, at the Shangri-La Dialogue, the Western officials strongly condemned China’s illegal activities in the South China Sea. Then US Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis warned of grave “consequences” should Beijing continue to violate international law. France and Britain also called for a joint task force to ensure the freedom of navigation in the contested water.

Floating nuclear plants: Lastly, China has already begun the construction of its first floating nuclear power plant in the South China Sea. In 2016, China General Nuclear Power (CGN) announced plans for a floating nuclear reactor that would be ready by 2020, which was followed by a joint-venture for another offshore reactor with China National Nuclear Corp (CNNC). All told, China envisions 20 floating nuclear plants in the South China Sea; since this fleet will be stationed in a heavily disputed maritime domain, legitimate questions can be raised about their international legality, safety oversight, and liability in the event of a nuclear accident. There is also the matter of whether these reactors will ultimately have a military purpose, given the scarcity of land and human settlement in the area and growing number of Chinese military facilities.

Why South China Sea matters for Canada?

Any shift that alters the status quo in the Indo-Pacific region may carry both economic and strategic consequences for Canada. The US and the other western allies have shown firm support to contain China’s aggressive rise in the South China Sea, while Canada’s response has been relatively muted. Considering the following points might help Ottawa adopt a more pragmatic approach to this problem.

First, Canada should support its western allies in the South China Sea. US Navy has challenged China’s illegal maritime claims by conducting ambitious freedom of navigation (FON) exercises, sailing within 12 nautical miles of Chinese-claimed islands. Countries like France and the UK have openly supported such operations and deployed warships through the South China Sea. At the Shangri-La Dialogue earlier last year in Singapore, France’s Minister of the Armed Forces Florence Parly announced that a French maritime task group, together with British helicopters and ships, have sailed through the South China Sea. The UK also intends to deploy its new aircraft carrier, HMS Queen Elizabeth, to the Indo-Pacific in 2021. Of note, in early 2018, Mark Sedwill, British National security Advisor said that carrier would eventually need the support of allies for high-end combat mission – and specifically mentioned Australia.

Of course, it’s more uncertain whether the UK and France are challenging these excessive (and illegal) maritime claims by simply transiting close to the claimed by China, or have taken the next step of adopting the more aggressive US-style FON exercises that go within the 12 nautical miles of them. Yet it is notable that these countries are openly discussing the need for freedom of navigation and are adopting increasingly ambitious deployments, in response to the US call for allies to support its FON efforts.

Like these countries, Canada has also sent its warships for exercises in the South China Sea, as part of its plan to send up to two frigates a year to the Western Pacific. Yet Ottawa has also tended to downplay the nature of these deployments, preferring to call them “presence patrols” rather than FON operations, even if this has not stopped China from shadowing these ships. Unlike our allies, Ottawa has shown little appetite to undertake ambitious operations. Notably, in April 2018, the Senate passed a motion criticizing China for its hostile behaviour in the South China Sea, but the government’s response was muted at best.

The country needs to do more in terms of supporting its allies, especially the US in its FON operations. It should first more openly label its deployments freedom of navigation, as a signal that Canada is fully on side with its allies when it comes to the South China Sea. It should also be prepared to undertake more ambitious FON operations, as it currently transits some distance away from these islands and artificial reefs claimed by China. Lastly, it should assess the risks (and possible benefits) of transiting within the 12 nautical miles of these islands, similar to how the US currently undertakes FON missions.

Conclusion

China has begun to alter the strategic balance in its favor in the South China Sea. Other SCS claimants have even been enticed by the potential economic gains that can be gained through China. Yet Beijing’s continuing violation of international law will dwindle down the importance of multilateral institutions. Canada needs to understand both what is at stake in the South China Sea and why the US is working so hard to ensure freedom of navigation in the region. Canada should not only back the US to share the burden of “global security” but also for its own national interest.

Irfan Yar is a counterterrorism and foreign affairs analyst, and currently a research intern at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.