By Jon Hartley, March 30, 2023

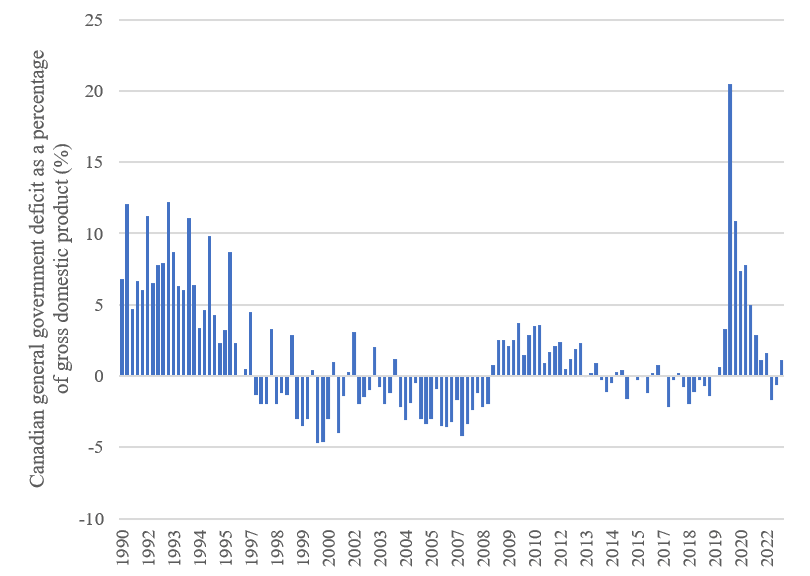

This week marks the release of the 2023 Liberal government federal budget, which increases deficit spending amid ill-suited macroeconomic conditions. With inflation still elevated, more government spending, to the tune of $43 billion deficit this year, can make inflation worse. Instead, the Trudeau government has decided to introduce so-called inflation relief payments to ironically quell inflation that may very well be partially a result of government spending during the pandemic (Figure 1).

The main increases in the budget are concentrated in health care, clean energy, and “grocery rebate” payments, the latter meant to help those most hurt by inflation. Nonetheless, most of these new spending initiatives reflect a government that is not seriously willing to take on the issue of inflation by reducing the growth rate of government spending.

Figure 1: Canadian general government deficit (as a % of GDP)

Source: StatsCan.

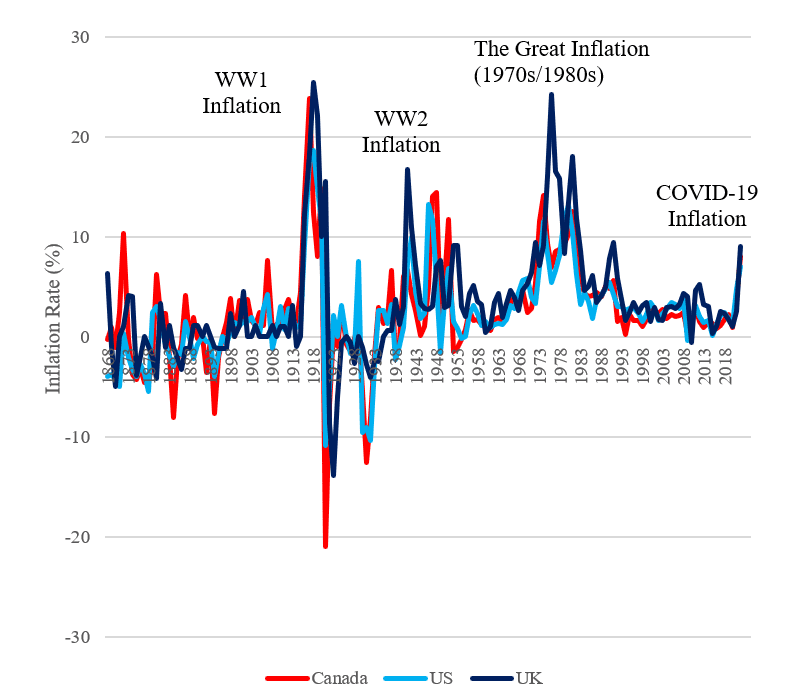

As of February, Canada’s annualized inflation rate remains elevated at 5.2 percent, well above the Bank of Canada’s goal of 2 percent. Inflation, excluding food and energy, remains at 4.8 percent. This is not to be taken lightly; the latest inflationary spike marks one of the largest inflationary spirals in Canada’s history next to the Great Inflation of the 1970s-1980s and the inflation from the First and Second World Wars (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Inflation rates for Canada, the US, and UK (1868-2022)

Sources: Rogoff and Reinhart (2009), US Bureau of Labor Statistics, OECD.

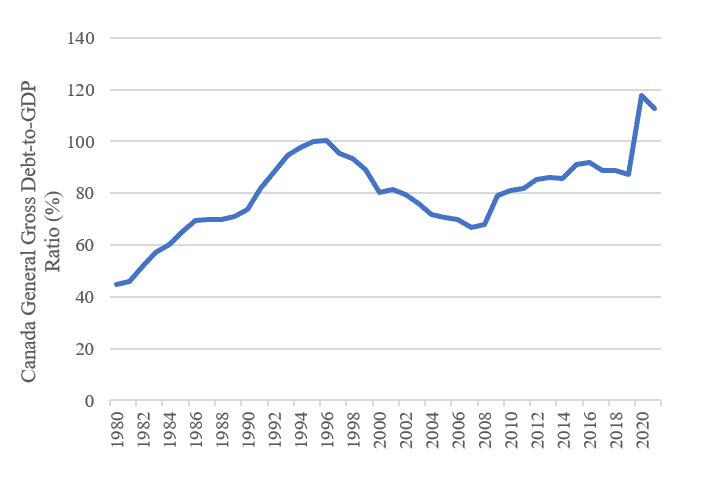

In response to high inflation, the Bank of Canada has rightly raised interest rates. Higher interest rates also mean higher debt service costs, making the path of debt potentially even more bleak. Canada’s federal debt grew enormously during the COVID-19 crisis, and it is now saddled with general gross debt levels around 100 percent (which includes federal, provincial and government debt) rivalling that of the 1990s. Gross debt-to-GDP levels above 100 percent are often correlated with lower economic performance as measured by GDP growth. Note gross debt does not include net assets from CPP and QPP (net debt measures that the government often cites do include CPP and QPP net assets but do not include corresponding future pension obligations/liabilities associated with the assets).

Figure 3: Canada general gross debt-to-GDP ratio (1980-2021)

Source: IMF.

The Canadian economy is clearly running near full potential with unemployment near 5 percent. Throwing more government spending fuel on the fire likely would make the Bank of Canada’s job of reducing inflation more difficult.

New stimulus payments amid high inflation

Central to the new spending in the federal budget are so called “grocery rebates,” which are very similar to the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) stimulus checks paid out by the federal government during the pandemic. The term “grocery rebate” is in fact misleading as individuals can do whatever they want with it. The stimulus checks are expected to cost around $2.5 billion and provide eligible couples with two children a one-time payout of up to $467, and single Canadians without children a payout of up to $234. Such payments are made through the Canada Revenue Agency.

The state of California in the US sent out similar one-time checks (which they labelled the “Middle Class Tax Refund”) earlier in late 2022 and early 2023.

Such repeated rebate initiatives fail to understand their unintended consequences: the potential to cause more inflation. From a political economy point of view, one can see how there is a dangerous political incentive to provide more cash relief to help with affordability during times of high inflation, which further stokes demand and raises prices even higher, contributing to an inflationary spiral. All of this makes the central bank’s job of bringing down inflation potentially even harder.

Some other planned increases in welfare benefits in the budget include increases to the Canada Worker’s Benefit, Old Age Security and Guaranteed Income Supplement benefits, climate action incentive and the Canada Housing Benefit.

Electric vehicle subsidies, in competition with the US Inflation Reduction Act

With respect to clean energy, the Liberal federal budget includes a tax credit for equipment used to produce electric vehicles (EVs), which is in large part a response to the US Inflation Reduction Act that subsidizes American-made EVs.

One important question is to what degree these subsidies will pass-through to higher EV prices versus actually delivering benefits for Canadians. Ford announced it was raising the price of its electric Ford F-150 by $8500 immediately after the announcement last August of the Inflation Reduction Act’s EV tax credit of up to $7500 for new plug-in electric vehicles in Internal Revenue Code Section 30D.

Increasing public funding for carbon-capture projects in order to compete with US green subsidies recently passed in the Inflation Reduction Act seems to be overkill for a Canadian economy that already has a carbon price of $65 per tonne, which is only set to increase in future years. Canadian carbon emissions have also started to plateau like many advanced economy countries.

It’s also important to remember that EVs are no panacea to a “net-zero” economy. The electric energy used to fuel EVs is still carbon intensive. That said, EVs will become mainstream when they become price competitive, which may very well occur on its own without government subsidies.

Increasing government spending on EV subsidies while inflation remains high is hardly prudent. Canada will never be able to compete with other countries like the US when it comes to industrial policy. Despite being well intentioned, such measures often amount to considerable amounts of corporate welfare instead of increased consumer benefits.

Increased health care spending and public dental benefits

The budget also notably includes $7.3 billion over the next five years for expanded public dental benefits and $22 billion on additional health care spending as part of the federal government’s recent deal with the provinces.

Increasing public dental benefits for uninsured Canadians with household income below $90,000, a result of the Liberal’s confidence-and-supply deal with the NDP that prevents an election prior to 2025, is arguably a hugely unnecessary expansion of a middle-class government benefit in a time of inflationary crisis.

Proposals to further increase federal health payments to provinces also are poorly timed given the inflationary environment. As broken as the Canadian health care system may appear to be at present, simply throwing more money at the problem does not fix deep structural issues.

The Canadian health care system suffers from a problem of no competition, which leads to shortages in the supply of doctors and shortfalls quality. Politicians like Danny Williams (Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador), who extol the virtues of the Canadian health care system, famously traveled to the US for medical care.

Private sector practices have been introduced to the UK National Health Services (NHS) to improve efficiency and increase competition with some success. Many other countries like Australia have two-tiered public-private health care systems that work fine. If the UK can introduce structural reforms to its health care system, so can Canada.

Reducing existing public sector costs and employment

The Trudeau government deserves some credit on making an attempt at cost cutting such as saving $7 billion over five years through reduced travel, outsourcing, and fewer management consultants. Nonetheless, spending in the area of professional and special services, while growing exorbitantly from $8.4 billion to $21 billion during Trudeau government years (from the 2015-16 fiscal year to the present fiscal year), makes up a small fraction of overall federal government spending.

One could argue that the Trudeau government should go much further in reducing the size of public sector employment. The private sector is starved for labour given the still significant divergence in labour demand and supply; the number of job openings dwarf the number of job seekers. Hence, now would be a great time to reduce size of government in a manner that could help deal with both private sector labour shortage and looming debt issues simultaneously.

There remains little evidence that Canada is heading for a severe recession that would justify massive investments in new public spending. The evidence around elevated inflation levels suggests quite the opposite.

There are also elements to the budget that seek to limit “junk fees” (hidden or unexpected consumer fees), taking a further page from the Biden administration – a policy topic that was featured heavily during President Biden’s 2023 State of the Union Address. While there is some academic evidence that such initiatives improve welfare, they have very little budgetary impact.

Conclusion

In sum, despite some small attempts to make some spending cuts, slowing the growth in the overall size of government is clearly not the main objective of the Trudeau government’s budget. Given the current elevated levels of inflation, one would think they would take it much more seriously. Instead, new spending programs from direct cash support, dental care subsidies, EV subsidies and health care spending are more important.

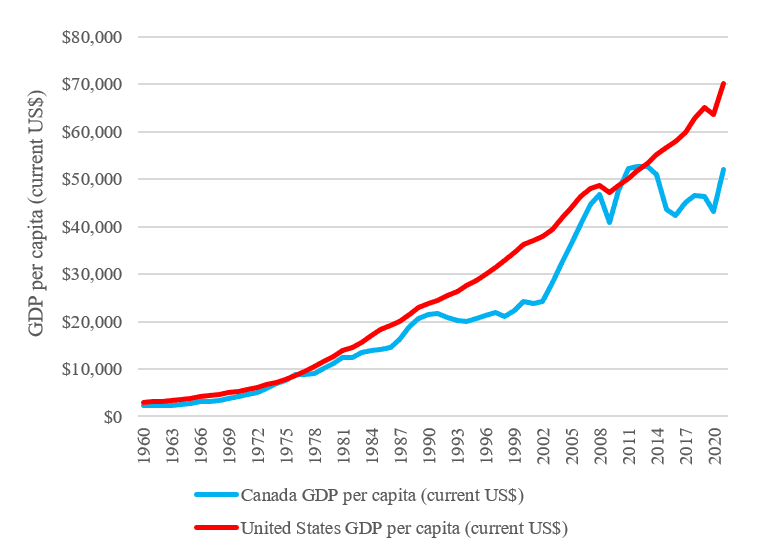

Slowing economic growth is an even deeper problem that has the potential to contribute to a worsening fiscal situation for Canada. Canada’s real GDP per capita has been nearly flat over the past decade, while the US GDP per capita has continued to grow albeit at a much slower clip compared to the 20th century (Figure 4). American incomes are now shockingly 40 percent larger than Canadian ones.

Despite significant immigration that ameliorates slowing population growth, without increased productivity and per capita economic growth, growth in the tax base will not be able to keep up with the growth in spending.

Figure 4: Canada and US GDP per capita (current US$)

Source: World Bank

Jon Hartley is a PhD student in economics at Stanford University and a research fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity.

References

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2009. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey.