Ottawa needs to be strong and principled in its dealings with China, not weak and accommodating, writes Charles Burton.

Ottawa needs to be strong and principled in its dealings with China, not weak and accommodating, writes Charles Burton.

By Charles Burton, February 1, 2019

There is no turning back this clock.

The Chinese government’s ugly response to the arrest of Huawei chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou – both the arbitrary “hostage diplomacy” arrests of Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, and the “death threat diplomacy” of resentencing alleged drug smuggler Robert Schellenberg from prison to execution – has led to revulsion and repugnance across Canada.

China and Canada now have to come to terms with the fact that – even after Ms. Meng leaves the comfort of her Vancouver mansion to either face U.S. justice or fly back to Beijing unextradited, and Mr. Kovrig and Mr. Spavor are freed from harsh punitive custody in secret interrogation jails – there will be no return to the diplomatic dynamic that existed before the Huawei executive’s detainment. Beijing’s dark retaliation will have a permanent and far reaching impact on future Canada-China relations.

In retrospect, we can see that Canada’s approach to China, up until the detention of the two Canadians, had become dysfunctional. It amounted to a foreign policy designed to serve the interests of Canada’s business and government elite, emphasizing, over all else, the promotion of Canadian prosperity by seeking greater access to China’s burgeoning market.

Beijing dangled the prospect of vast riches to starry-eyed, greedy vested interests, but demanded major concessions in return. These included: the removal of legal barriers to Chinese state acquisition of companies in Canada’s energy and resources sectors, and allowing imported Chinese workers to build the necessary infrastructure; letting China acquire Canadian technology without “discriminatory trade restrictions”; signing a functionally one-sided extradition treaty so Beijing can seize Chinese expats who had fallen afoul of the regime and fled to Canada; and, despite dire warnings from Canadian security officials and their counterparts in the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing consortium, the installation of Huawei 5G technology throughout our telecommunications networks.

Some in Ottawa did not want to scuttle a trade deal by doing anything deemed by the Chinese embassy as offensive or “hurting the feelings of the Chinese people”, such as challenging the activities of their intelligence operatives in Canada. For example, when a closed-door parliamentary panel discussion last fall published its report, it noted that “panellists agreed that it was important for Canada to avoid the excesses that have characterized the Chinese interference debate in the U.S. and Australia … The fact that Australia turned to new legislation as well as the creation of a ‘National Counter Foreign Interference Coordinator’ should … not be taken as a model to be replicated” by Canada.

So, if Ottawa was considering the appointment of such a co-ordinator, or the allocation of more, and desperately needed, resources to the China operations of the RCMP and CSIS, this parliamentary panel put that thinking to bed, as they would lead to bad consequences for people who are friendly or possibly beholden to Beijing. “The bigger issue that all parties need to keep in perspective,” declared the panel, “is Canada’s relationship with China, and how to build stronger political, economic and cultural ties that are mutually beneficial.”

Presumably the same ethos of avoidance would apply for Canada’s response for any number of issues, including the rights of interned Uyghurs, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Tibet or China’s military expansion into the South China Sea which blatantly violates international law.

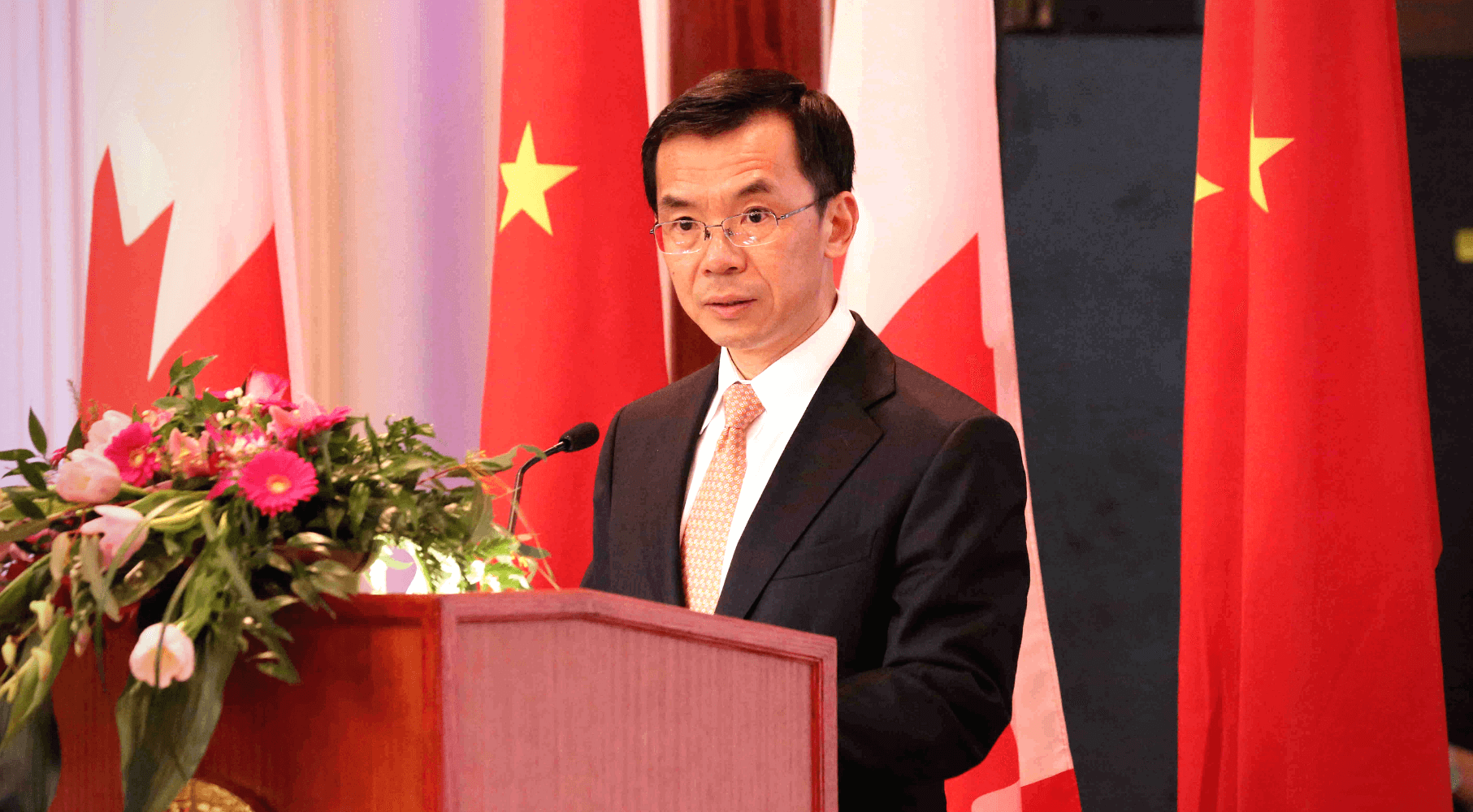

An article this week in China’s Global Times revealed its government’s anger at the firing of Canadian ambassador John McCallum, a decision it characterized as “political interference.” The article attributes Ottawa’s “stand against Beijing” to pressure from “Canada’s current public opinion” instigated by “some Canadian media and reporters.” Beijing wants their Canadian China-friends to get back into line, threatening that “the Trudeau government must properly deal with China-Canada relations, or it should be prepared for Beijing’s further retaliation.”

Further retaliation or not, a Canadian prime minister cannot order a judge to authorize the return of Ms. Meng to Beijing. Hopefully, during her upcoming extradition hearing, she will cut a plea bargain with the U.S. authorities to go to the United States voluntarily, and put an end to this nightmare for Canada.

If, as part of this deal, Ms. Meng was prepared to explain to the U.S. government exactly what the relationship is between Huawei and China’s intelligence, security and military apparatus, that would certainly clarify things for all of us, including how – or if – the Canada-China relationship can be reset.

Canadian public opinion will never enable Ottawa to grant the concessions Beijing wants. The post-Meng relationship requires that Canada regain the respect of China’s regime by standing up for our interests and values. In this complicated landscape, Ottawa needs to be strong and principled – not weak and accommodating.

Charles Burton is an associate professor of political science at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont. and is a former counsellor at the Canadian embassy in Beijing. He is senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Centre for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.