It’s clear that both Russian and Chinese leadership view international affairs through a power and strength Machiavellian prism, writes Stephen Nagy in the Japan Times.

It’s clear that both Russian and Chinese leadership view international affairs through a power and strength Machiavellian prism, writes Stephen Nagy in the Japan Times.

By Stephen Nagy, February 15, 2022

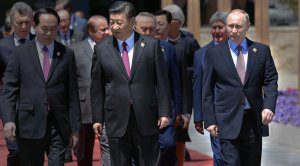

As Chinese President Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, looked over the opening ceremonies of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, we saw the two strongest authoritarian leaders presiding over a superbly choreographed Olympic ceremony, sending a unified signal of dismissiveness and confidence to their domestic and international audiences.

One of the highlights of the ceremony was the emphasis on ethnic harmony within the Chinese context and the ethnic Uyghur who lit the final Olympic torch. It was an explicit message to the international community that the Chinese Communist Party willfully dismisses the very well documented human rights abuses against the Uyghur people in Xinjiang province.

It was also a clear sign that Beijing fully rejects the well-founded criticisms leveled against the National Security Law, which breaks the “one country-two systems” promise in Hong Kong, and against its growing belligerence towards democratic Taiwan.

The ceremony also flaunted confidence that these two leaders were willing to come together to show their united position on critical areas of crisis such as the tensions over Ukraine.

As Russia massed troops along the border to pressure the Ukrainians and the Western alliance powers to not admit Ukraine into NATO, Xi Jinping wanted to express his support for Putin’s efforts to maintain Moscow’s sphere of influence in its backyard.

This support is an implicit quid-pro-quo. Xi is expecting a similar kind of support for China’s position on Taiwan, as well as in the South and East China Seas. Ironically, this is in direct contradiction of China’s long-standing calls to end “cold-war style” spheres of influence and noninterference in the affairs of other states.

The question here is whether Putin and Xi’s dismissiveness and confidence are based on a sense of self-assuredness with their political, economic and institutional systems or if it is performative and defensive as both of their authoritarian systems are seen as corrupt, nonrepresentative and propped up by the quashing of dissent and political pluralism.

An interesting figure from within the Chinese context is the year-by-year, double-digit increase in the military budget, which is less about the projection of military power abroad and much more about empowering the domestic surveillance system and re-enforcing domestic security to ensure that the Communist Party remains in power.

A confident leader in an institutionally robust system shouldn’t need to invest so much in protecting themselves against their own people. However, what we see is technology being used to monitor and control its citizens.

This techno, Leninist-Marxist state organization is further propped up by a massive propaganda apparatus to ensure that ideologically, educationally and in terms of how business interacts with the state are in service of the party.

Similarly, within the Russian context, a confident leader in a self-assured state would be able to allow open elections and freedom of speech, as well as dissent and debate on key issues facing the Russian people.

Despite efforts by China and Russia to exhibit confidence, dismissiveness and unity at the Olympic ceremony, the take home message for many observers is the similarities in terms of the lack of confidence in their systems.

So how should democratic countries like Japan, Canada and the United States, as well as like-minded countries, confront these two authoritarian states?

Is it best to confront them through security cooperation by enhancing their collective deterrence capabilities within the East and South China Seas and more broadly through the Indo-Pacific region?

Do they confront them through coherent and cohesive comprehensive economic policies in which they pursue a path of creating trade rules both in the traditional economy, as well as in the digital economy to shape behavior online and offline with like-minded countries?

Should they invest in building institutions through infrastructure connectivity, promoting good governance and shared norms within the Indo-Pacific, or do they invest in enhancing some of the existing divisions within these two societies that are more fragile than their propaganda machines lead the world to believe?

In essence, all four strategies are needed to put pressure on both authoritarian regimes to push back against their expansionary behavior within their respective regions. In the case of Russia, it will continue to be important to put pressure on Putin and his supporters by cutting off their access to travel, to the international banking system and to exporting energy.

Simultaneously, drawing strong lines of united support with the European Union and the United States to ensure that any kind of invasion, either direct or through gray-zone operations will be fiercely resisted by a united Europe backed up by the U.S., Canada and other countries.

Japan has a delicate balance here as Tokyo is concerned about further pushing China and Russia together in their backyard. The last thing Japan wants is a deepening relationship between Russia and China.

Japan may have to find a way to draw a line of distinction between its support for the European Union and the United States in their defensive initiatives on protecting Ukraine’s borders with Russia while ensuring that it doesn’t push Moscow deeper into Beijing’s geopolitical orbit.

In the case of China, this is a much more complex discussion because it, after all, is the second-largest economy and that economy fuels not only its military growth but its ability to influence its neighbors in Southeast Asia, Japan, Korea and other parts of the region.

Here again, liberal, democratic powers need to come together to ensure that Beijing understands that there will be serious consequences for a forced unification of Taiwan and for further expansionist policies aimed at creating an “Indo-Pacific region with Chinese characteristics.”

These could include restricting travel visas for mainland Chinese students, academics and Chinese Communist Party members and their families. Sanctions on Chinese businesses, cutting off access to Western countries by Chinese media organizations such as the CGNT and China Daily, as well slapping economic sanctions on businesses associated with the party itself, should be explicitly articulated as consequences that will result.

It’s clear that both Russian and Chinese leadership view international affairs through a power and strength Machiavellian prism. They will not compromise with countries that demonstrate weakness.

It will be critical for democratic powers — working with like-minded countries — to find ways to create military, economic and institutional deterrence capabilities to ensure that these two authoritarian states cannot pursue their expansionist policies.

At the same time, they should work to enhance the internal divisions within these societies and promote their own good governance, democratic principles, human rights and equitable socioeconomic development.

Only by offering a better example can they convince their citizens that open and democratic societies can offer the stability, growth and good governance they are looking for in their own governments.

Stephen Nagy is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University in Tokyo and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.