By Barry Prentice

August 24, 2022

Canada is a massive country, with its population mostly concentrated in a thin band near the 49th parallel. This is its strength as well as its weakness. Canada has enormous reserves of natural resources, and it is a homeland to Indigenous and northern communities that have developed unique cultures and traditions absent the homogenizing forces of southern cities. But the sparsity, vastness and extreme weather make much of the country difficult and expensive to access. This has impeded the competitiveness of its resource sector and made the provision of basic public services, from health care and education to clean water and healthy food, a luxury rather than a right in the more remote regions.

There are 292 communities in Canada assessed as remote, meaning they are only accessible by air for most of the year, with alternative forms of transportation either non-existent, impossible or impractical. Transportation accessibility has been a chronic problem for northern Canada. As Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King observed in 1936, “if some countries have too much history, we have too much geography” (quoted in Ratcliffe 2016).

Airships – lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate under their own power – were flying across the Atlantic Ocean when Mackenzie King made this statement, but various technical problems meant they never took off commercially. Eventually they were displaced with fixed-wing aircraft. Eighty-six years later, a new generation of cargo airships could fill an important gap in Canada’s national strategy for transportation. But despite the absence of any other ideas to improve transport accessibility for the North, the Government of Canada has ignored cargo airships as a possibility. No policy is not a policy, and climate change is making the status quo untenable. Temporary winter roads are more dangerous, while melting permafrost threatens what little existing infrastructure has been built. Can airships offer a solution?

This paper will examine the viability of cargo airships to address the northern transportation puzzle. With lower greenhouse gas emissions, attractive economics, year-round applicability, and much smaller footprint on the land than a connecting gravel road, airships are a solution to northern communities and mines’ cargo needs whose time has come.

Canada’s transportation policy

On November 3, 2016, then Minister of Transport Marc Garneau presented Transportation 2030, his strategic plan for the future of transportation in Canada (Transport Canada 2016). The Transport 2030 vision sets out five themes, each of which will be explored in turn.

“Waterways, Coasts and the North”

Economically, Canada is like two countries. About 30 percent of the landmass has low-cost access by all modes of transport and a highly developed economy. The other 70 percent is an underserved frontier. Poverty begins where the all-weather roads end. Remote communities that depend on seasonal ice roads for inland transport have over 50 percent unemployment, as do isolated communities on the coast that depend on annual sea lifts.

Enhancing northern transportation infrastructure is a stated goal of Transport 2030. The challenges are costs and climate change. On average, gravel road construction costs $3 million per kilometre in the Canadian Shield and the North. Just to convert Ontario’s 3000 kilometres of ice roads to gravel would cost over $9 billion. The number of ports required in the Arctic is similarly unaffordable.

Lack of reasonably-priced, year-round cargo transport leads to poor living conditions. The pandemic has shone light on its consequences. Food insecurity, overcrowded housing and underlying health problems (e.g., diabetes, mold aliments, tuberculosis) made Indigenous populations extremely vulnerable during the pandemic. These unacceptable conditions all stem from a lack of reliable, affordable freight delivery throughout the year.

The economic disparities in remote communities are growing wider. Even with the $130 million food transport subsidy that the federal government provides each year, food prices in the North are still sky-high. Cargo airships could provide year-round service and cut freight costs in half. They would enable housing construction to continue throughout the year and make nutritious food affordable. In a matter of years, cargo airships could reduce or even eliminate the need for any food transportation subsidy.

“Green and Innovative Transportation”

Climate change is demanding action on adaptation strategies for the North. Since 2000, the ice roads have lost half their season and the risks of accidents are increasing. Existing roads and landing strips are vulnerable because the permafrost zones are becoming more active. Impassible sections of sinking and buckling infrastructure are now a feature of Northern transportation.

Electric airships powered by hydrogen fuel cells fit the second theme of Transport 2030. Zero-carbon-emissions airships are being designed that could carry two or three tractor-trailer loads of freight. Some ground infrastructure is needed, but the footprint in the North would be minimal. Airships are a green technology. They will create new supply chains and stimulate employment and investment in the aerospace sector.

“The Traveller”

This Transport 2030 theme focuses on air passengers who want greater choice, better service and lower costs. Nowhere in Canada is the need for better air service more pressing than in the North. An air ticket from Winnipeg to Churchill, Manitoba costs more than a flight to France. Combi-passenger/freight airships could carry passengers with freight. This could provide air travel service at less than half the cost of current airlines.

The large capacity of airships is also an advantage for moving people who have medical conditions. Space exists to position cots where patients could rest and be treated, while on their way to specialized care.

“Trade Corridors to Global Markets”

Canadians appreciate transportation’s role in trade and prosperity more than most nations. The distances are vast, and shippers depend on a few key transportation routes to connect to global markets. The need to improve and enhance Canadian trade corridors is an important theme in Transport 2030. In no other part of Canada does the absence of established trade corridors limit economic development as much as in the North.

Trade corridors are often described in terms of roads, railways, pipelines and ports, but air-based trade corridors can be just as important. Known mineral deposits dot the Canadian Shield and the Arctic that could be opened up using airships to gain access. Mining developments would bring prosperity to the local inhabitants of North, and mineral exports would contribute directly to Canada’s balance of payments.

The role of air corridors has been increasing for global trade because more cargo jets are being put into service. Airships are a better alternative. Very little freight needs to fly at 800 kilometers per hour, and jet airplanes have the most carbon emission per tonne-kilometer of any mode of transport. Electric airships could cross the Atlantic or the Pacific in sufficient time to meet freight demands.

Cargo airships could also establish new international trade corridors. For example, airships could deliver fresher fruits and vegetables from the Caribbean and South America. And, on the return trips, they can deliver Canadian agricultural exports back to these tropical populations.

“Safety”

Transport 2030’s fifth theme, safety, is always the number one concern for any transportation company. Contrary to popular myth, airships are inherently safe. Yes, airships accidents occurred during the 1930s, but even more lives were lost in airplane crashes, and they continue to happen. Aviation technology has come a long way in the last nine decades. Airworthiness regulations guarantee that only safe aircraft are permitted to fly. The same advances in aerospace engineering and materials can make airships as safe as any other aircraft today.

Snow blindness

Modern airships check all the boxes of the Transport 2030 policy themes. Airship technology can provide the basis for a strategic plan that offers a safe, green, innovative and integrated transportation system that serves the whole nation. Why do airships in the north seem to be such a good idea in theory, but have so much trouble getting off the ground in practice? Let’s take a closer look at airship technology to see whether, or not, it has an inherent flaw that causes politicians and government officials to ignore this solution to northern transportation. Subsequently, the political sphere is explored to seek a way forward.

Everything old is new again

Windmills, electric cars and dirigibles were all commercially available in the 1920s and 1930s, but they did not survive the 1940s. All three of these technologies disappeared for the same reason: cheap fossil fuels. Coal-fired electrical plants replaced wind power. Gasoline automobiles displaced electric cars. Kerosene-turbine powered jet airplanes out competed the dirigibles. Of course, these carbon-based technologies also offered advantages. Electricity from the grid was more reliable than windmills. Gasoline cars offered much better range than electric cars. Jet airplanes were so fast and efficient that not only did they end the passenger airship era, they also terminated ocean liners and transcontinental railways.

Electric cars and wind turbines are back with a vengeance. Better batteries and hydrogen fuel cells have extended the range of electric vehicles. Several countries are even mandating an end to the internal combustion engine. Wind turbines are less expensive and much less polluting than coal-burning power plants. Economies of size and new designs have made wind turbines the fastest growing source of electrical production. Two of these green technologies are back: why not electrically-powered airships?

The viability of airships as a mode of transport does not need to be proven. The German Zeppelins were able to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a scheduled basis, cruising at 145 kilometers (80 miles) per hour. They offered a useful lift of 70 tonnes, configured as luxury accommodation for 72 passengers. Early airships were certainly labour intensive with 40 flight crew and 10-12 stewards and cooks.[1] With modern materials and control systems the same size airship could provide 100 tonnes of useful lift and operate with a crew of three. Looking ahead, most cargo airships will likely operate as drones (i.e., remotely-piloted).

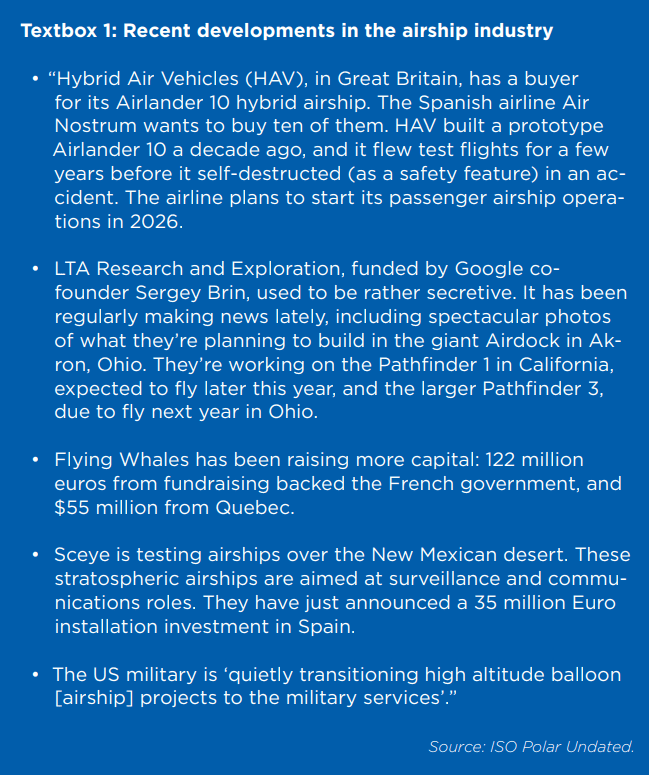

Modern airships will be safe. The main source of airship accidents in the 1930s was structural failure. Strain gauges did not exist, which meant that engineers were left to try estimating stress concentrations with nothing more than a slide rule. Today, with computer simulations and advanced materials, no technical barriers inhibit the production of robust and reliable airships. Some more recent developments in the airship industry can be found in the following textbox.

What has also changed is the market. Airships are unlikely to challenge jet airplanes for passenger traffic despite the jet’s huge carbon emissions. Speed matters for passengers. Where the airships can shine is in freight transport. Two days to cross the Atlantic Ocean and five days to cross the Pacific Ocean is more than fast enough for any freight shipments by airship. An electrically-propelled cargo airship, using hydrogen as fuel, could cut the cost of air transport by more than half. In fact, a cargo airship could earn carbon credits to offset jet passenger airliner emissions.

Three outstanding problems

The reasons behind the delay in building cargo airships are economic and regulatory. An economic barrier is the size of the MPV (minimum viable product). Airships, like ships of the ocean, experience significant economies of size. The bigger they are, the lower their unit cost. However, the minimum size at which they become economic is still quite large. Relatively small inflatable airships (blimps) are used for advertising and sightseeing. But even at 80 meters in length, they can only lift about 2 tons, which is insufficient to carry freight profitably.

Rigid airships, like the Zeppelins, are more appropriate for cargo but the MPV is enormous. The Zeppelins were over two football fields in length, and as high as a 12-story building. Before anyone could consider building such an airship, they need a hangar with a huge door for its construction. A few airship hangars capable of handling such a large craft in the US remain from the pre-war era, but none were ever constructed in Canada. Unlike the MPV for an electric car or a wind-turbine, cargo airship prototypes cannot be cheaply made, and subsequently scaled up for commercial use.

The second barrier to the rebirth of the airship industry is the perceived helium shortage and the hydrogen gas paranoia. Helium is derived as a by-product of natural gas extraction where its concentration is sufficient to justify a refinery. Over time, a number of critical uses have developed, like the manufacture of computer chips and operating MRIs. The cost of helium has risen steadily, and airships are viewed as a lower-value use. From an airship investment perspective, the finite supply of helium and its price raise question marks.

Hydrogen is the obvious lifting gas for airships. It has 8 percent more lift, an endless supply and costs a fraction of the price for helium. Hydrogen was widely used outside the US prior to the Second World War. However, investors are likely to be scared off by the absolute prohibition of the use of hydrogen gas that is embedded in the Canadian and US air regulations.

The history of ban on hydrogen for use as “lifting gas” in airships precedes the Hindenburg accident by 14 years. Although this accident is commonly confused as the reason, the U.S. government banned the use of hydrogen gas in military airships in 1923. The ban was a political decision based on neither scientific, nor engineering research, but came after a successful lobbying effort by helium interests.

After the war, the ban on hydrogen was extended into the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulations. As the world’s leading air authority, the FAA rules were “rubber stamped” into the air regulations of many other jurisdictions. This is how Canada came to have a ban on the use of hydrogen as a “lifting gas” in airships, while never having had a single airship built here.

In the past century, knowledge of hydrogen and how to handle it safely has greatly expanded. Hydrogen gas is used widely as an industrial input, and to power fuel cells in buses, cars, trains, fork-lifts, and soon in airplanes. The ban on hydrogen’s use in airships is an anomaly. Until the ban is removed, Canadian investors will be nervous about backing hydrogen airships. However, this is changing. The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has proposed new regulations for airships that will permit any gas to be used, as long as the developer can prove its airship is safe. Once the Europeans and Asians go in this direction, Canada and the US are likely to follow.[2]

The third and perhaps most important barrier to the airship industry is the failure of government policy and engagement. The role of government is crucial because transportation is a shared private-public responsibility. The government sets the rules and supplies the long-lived, fixed assets, like roads, harbours and airports. In all history, no new transportation system has ever been successfully introduced that did not have strong government support and encouragement. One cannot imagine the transcontinental railways being built across Canada if the government had been non-committal. Great Lakes shipping would have never grown without government construction of the Welland Canal and the St. Lawrence locks.

The government does not have to initiate or solely fund a new transportation system’s development, but it cannot remain silent and hope that it emerges spontaneously. Ignoring and shunning a new transportation technology is equivalent to condemning it. The treatment of the airship technology in Canada explains the lack of business confidence in this country’s airship development.

No mojo

When did Canadian governments lose their mojo? It is hard to identify any significant national projects since the Diefenbaker era. After pioneering CANDU reactors, microwave communications, Telesat, building the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Dempster highway, few signature projects have been led by federal governments in Canada.

Mariana Mazzucato at University College London has been researching the role of government in innovation and economic development. She builds the case for governments to lead breakthrough technologies, and points out that many of the innovations, from robotics to vaccines, were led by public institutions (Mazzucato 2015). Politicians have their role in technological development backwards. Where government leads, private money follows. Had NASA not invested in decades of research, neither Jeff Bezos, nor Elon Musk, would have invested a penny in space travel.

Put simply, Mazzucato thinks that governments were led astray in the 1970s by claims that “governments shouldn’t try to pick winners.” In the case of the North, this means that government should wait patiently and remote communities should accept prohibitively expensive options, until someone in the private sector takes all the risk to develop an airship that can solve our problems. With this kind of leadership, Western Canadians would be speaking with an American twang, because Sir John A. MacDonald’s government would have waited for private US railways to connect the Prairies to the world economy.

Politicians may be afraid to take chances on driving new technologies because of the criticism failures may bring. After Premier Brian Peckford’s efforts to establish greenhouse cucumber production in Newfoundland failed in 1989, he was hounded from office. Mazzucato notes that more failures than successes are a reality when something new is tried, but the results can still be very positive. The US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is an example of great breakthrough successes. They pioneered the Internet, GPS and Siri, just to name a few. They also had lots of failures, but only a few successes are needed to compensate for many failures. DARPA maintains that if more than 10 percent of their projects are a success, they are being too conservative.

Unlocking northern resource development

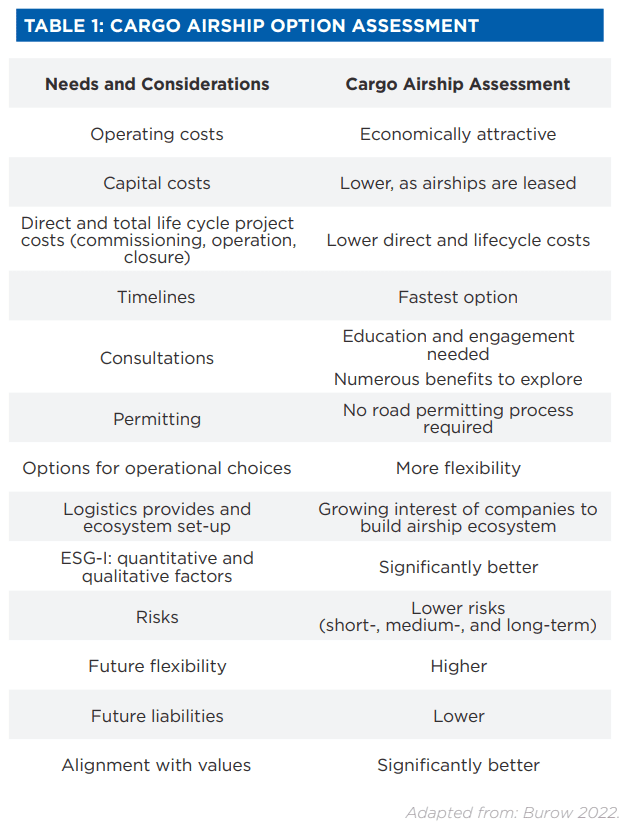

One obvious benefit to cargo airships is their ability to support mining operations in otherwise inaccessible locations. While northern Canada has incomparable geological potential, the lack of infrastructure and long permitting processes make it prohibitively expensive for project proponents. Airships can address the high costs involved in transporting ore to market; instead of having to construct roads or railroads, ore can be transported by airship to processing facilities year-round. This saves time, money and avoids environmental complications from roads and railroads that might impact, for example, caribou migration routes. Airships are also redeployable, further enhancing their economic attractiveness (see Table 1 for a cargo airship option assessment). They could provide a key to unleashing northern Canada’s critical mineral potential.

The North is the third solitude

Although more than 70 percent of Canada’s landmass lies north of existing roads, the majority of Canadians have never visited or have plans to visit this region. They may care about the gaps in socio-economic outcomes experienced by people living in remote communities, but they have no visceral empathy or experience. This is understandable because is it so expensive and difficult to travel north of the existing road network.

The same disconnect exists in the Ottawa bubble. It might be cynical to describe the bureaucracy as uncaring and disinterested, but unless they are directly responsible for the North, scant time is spent thinking about northern issues. Transport Canada has an office tower full of staff who are paid well to develop transport solutions. In the 20 years since the topic of airships has been brought to their attention, not a single study, report or policy statement has been made regarding an airship policy for the North. Worse still, the bureaucrats in Ottawa have come up with no ideas of their own.

Of course, the bureaucrats point to the politicians who are not giving them direction to research airship technology. The political reason is obvious. All the votes are in the cities. In the power centres of this country, the North starts at Barrie, Ontario! The Arctic is represented by only three seats in the Canadian Parliament.

Why aren’t northerners demanding airships? Many are starting to become aware of the opportunity, but there is no clear path for the idea to reach them. Only through occasional media stories or conferences does the concept get any promotion.

As our current Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, observes “The way to build a strong future is by both protecting the environment and creating good jobs” (Trudeau 2016). Electrically-powered cargo airships meet this criterion. They should be included in the Transport 2030 policy vision for the future of transportation in Canada.

About the author

Barry Prentice is a Professor of Supply Chain Management, at the I.H. Asper School of Business, University of Manitoba, and former Director of the Transport Institute (1996-2005). In 1999, National Transportation Week named him Manitoba Transportation Person of the Year. He was instrumental in founding a new Department of Supply Chain Management (SCM) at the I. H. Asper School of Business in 2003 that now offers undergraduate and graduate degrees in this field. In 2009, Dr. Prentice was made an Honourary Life Member of the Canadian Transportation Research Forum. Since 2015, he is a Fellow in Transportation at the Northern Policy Institute.

References

Burow, Christine. 2022. “Mining in the Remote Areas.” Presentation at the Airships to the Arctic 2022 Conference, May 26-27. Available at https://media1.cc.umanitoba.ca/legacy/Client_Deliverable/2022_05_26_Arctic_Airships_Day1__christine011859.mp4.

ISO Polar. Undated. “The coming giant airship renaissance: An investment opportunity, part 1.” ISO Polar. Available at https://isopolar.com/the-coming-giant-airship-renaissance-an-investment-opportunity-part-1/.

Mazzucato, Mariana. 2015. The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. PublicAffairs; Revised edition.

Ratcliffe, Susan, ed. 2016. Oxford Essential Quotations (4 ed.) Oxford University Press.

Transport Canada. 2016. Transportation 2030: A Strategic Plan for the Future of Transportation in Canada. Transport Canada. Available at https://tc.canada.ca/en/initiatives/transportation-2030-strategic-plan-future-transportation-canada.

Trudeau, Justin. 2016. “Statements by Members.” Hansard, 118 (November 30). Available at https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/house/sitting-118/hansard.

[1] Further information on the Hindenburg can be found here: https://www.airships.net/hindenburg/

[2] Most Asian countries and Australia have no restriction on the use of hydrogen in airships.