In the April 2015 edition of Inside Policy, the magazine of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, Globe and Mail columnist Jeffrey Simpson charts the search for a middle ground in the path to prosperity for Aboriginal peoples in Canada.

By Jeffrey Simpson, April 8, 2015

In some religious traditions, it is customary for a leading figure to deliver a sermon. Often, it revolves around a segment taken from a holy book. I take the liberty of borrowing from that tradition in citing the American author, the great William Faulkner, who wrote that “the past is never dead; it is not even past.”

Faulkner was a Southern American. Nowhere in the United States did/does the past weigh more heavily on – one might even say weigh down – society than the US South. The plantation economy. Slavery, the “peculiar institution.” The mythology of female virtue and gentlemanly gallantry. The Confederacy. The Civil War. Defeat after a dreadful struggle, followed by the dream palace memory of the cause aborted but kept alive in memorials throughout the South to “our glorious dead.” Always, there was the scar of race, so that negroes, as they were called for so long, became legally free but continued to be economically and politically bound. The Southern Way of Life meant that the “past” was “never dead” because it was “not even past.” It took a long, long time for the South to get over itself, to stop looking over its shoulder. Even today it sometimes seems as if some old habits are merely wrapped in new garb.

Of course there is also a big part of Canada’s past that is not even past, and it influences the country’s greatest future challenge: finding a better place for Aboriginal peoples in our society. We have failed in this challenge in the past, when we tried various approaches of assimilation that not only did not work but inflicted further damage on Aboriginals. There were other policies, too, that derived from racism: no voting rights, placing of Indians (as they were called then) on reserves, unequal treaties. All those failed policies haunt us still. They especially haunt Aboriginal people when they ponder their past that is “not even past.”

We non-Aboriginals tried subjugation and assimilation and it failed. We are now trying or at least accepting parallelism, even what I might call a radical parallelism. After almost half a century of trying this re-creation of a long-ago past in modern idiom, the least we can say is that progress has been, and remains, heartbreakingly slow.

Necessarily, I must leave much out in discussing the long history of Aboriginal relations in Canada. So I highlight two seminal events, among many, because each illustrates the two paths I just described. A terminological note: Although I am using the term Aboriginals for the most part, I am not talking about Métis and Inuit, but rather Indians, status and non-status, or First Nations.

In 1969, the recently elected government of Pierre Trudeau published a white paper on Indian policy. (Inside the government, it was called a “red” paper.) Consistent with Mr. Trudeau’s belief in individual but not collective rights, and reflective of the general frustration about the lack of progress on Aboriginal matters, the white paper recommended scrapping the Indian Act (which is what many Aboriginals said they wanted); delivering services through the same programs as for other Canadians; abolishing Indian Affairs special programs; and transferring Indian lands directly to Indian people and away from ownership by reserves.

Aboriginal leaders descended on Ottawa and furiously denounced the White Paper as a recipe for assimilation. They insisted that it undermined their special standing in Canada as the original occupiers of the land. They insisted that it diluted their relationship with the Crown that dated to the Royal Proclamation of 1763.

Trudeau retreated, not something he often did. The White Paper’s ideas reflected what was a modern-day idiom for an old idea, to do away with special status for Indian people, to make them more like “us,” in their own best interests of course. They did not see it that way.

Ever since, Aboriginal leaders and governments have tried to develop a functional, “nation-to-nation” relationship, without much success.

The next attempt to re-cast the relationship came when Prime Minister Brian Mulroney appointed the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Affairs in 1991. Again, it was an idea born in frustration about the lack of progress and the hope that new ideas might be injected into difficult, even intractable problems. The commission ran for five years, and went way over budget until it was given a produce-or-be-shut down edict by the Chrétien government.

Mulroney asked retired Supreme Court chief justice Brian Dickson to recommend commissioners. He did: four Aboriginals; three non-Aboriginals. Since judges like fellow judges, he suggested two of them, René Dussault from the Quebec Court of Appeal and Bertha Wilson, formerly of the Supreme Court of Canada, neither of whom had any experience with Aboriginal peoples, except as concepts. Judge Dussault became co-chair with Georges Eramsus, a prominent Dene leader from the NWT whom I had met and interviewed when he led the Dene Nation in its fight against the Mackenzie Valley pipeline in the 1970s. I later wrote a book chapter about him and his view of Canada. He was the commission’s driving force.

The commission produced five volumes of some 2,000 pages. I can lay claim – if that is the right phrase – to being one of a very few Canadians who read them all. Well, not the indices.

Along the way, after about two years if memory serves, something quite important happened inside the commission. The only non-Aboriginal with hands-on experience in dealing with Aboriginal issues – not as some abstract idea or as legal theory – quietly resigned. Allan Blakeney, a Rhodes Scholar and a former NDP premier in Saskatchewan, where more than 10 per cent of the population was and is Aboriginal, left because, as he told me later, he could not abide the slow and disorganized pace of the work, and because he thought the other commissioners were dreaming up unworkable non-solutions to what he, as a former premier, believed to be a series of practical problems. He did not think the intellectual direction of the commission would produce workable results. He was replaced by a former Alberta civil servant, Peter Meekison, a fine man whom I knew well, but without Mr. Blakeney’s hands-on experience and political savvy.

“Separate worlds” was the title of the first chapter of the first volume, describing a largely peaceful, productive, prosperous, even bucolic state of affairs that prevailed among Aboriginals before the arrival of our non-Aboriginal ancestors – or “settlers” as they were then and are now called by some of those who write about Aboriginal affairs, a classic example of the appropriation of a narrative that is politically motivated and condescending, especially in this province where people trace their lineage back 400 years, obviously not as long as Aboriginals in these parts but very long by any reasonable standard.

The presented history was an extremely potted one. There were indeed peaceful and productive relations among some Aboriginal peoples; there was also frequent conflict and violence. Only in the last few decades have relations between Iroquois and Algonquins been somewhat repaired. At one point, the Iroquois, especially the Mohawks among them, were fighting the Delawares, Susquahannas, Abenakis, Pequots and tribes (or nations if you prefer) as far west as the Illinois country, to say nothing of their mortal enemies, the Algonquins north of the St. Lawrence River. In the classic study of intra-Aboriginal relations in what is now Michigan and Ohio – entitled The Middle Ground – Richard White depicts the ongoing struggles among Aboriginal groups in that area long before – and after – “settlers” arrived.

It is absolutely true that the British, French and American colonists tried to exploit these rivalries to their advantages, but they did not create them. You only have to read Samuel de Champlain’s diary of the battle along the east coast of the lake named for him in which a handful of French soldiers killed a cluster of Mohawks to the immense delight of his Algonquin allies to understand that conflict was as much a part of inter-Aboriginal relations as peace and prosperity. I do not say this to sound superior. God only knows how often we non-Aboriginals from Europe have visited immense and violent miseries on each other: on this continent and in so many other parts of the world. I only mention it as a kind of mild corrective to one of the prevailing and misleading narratives that make dialogue and sound policy so difficult.

Who knows what, if any, influence Allan Blakeney might have had on the final report? He obviously concluded that he would have had none, and so he resigned. The result, which he foresaw, was a report based on what I might call parallelism: that would be two sets of peoples, as with the two-row wampum, with all sorts of diversity within each group, Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, just as the report argued there had been at the time of the first arrivals of the settlers and for some period of time thereafter.

Everything in the report was premised on parallelism. Wilson dreamed up the rules and structure for a separate Aboriginal parliament that would, by inventive legal reasoning, be connected to but remain separate from the Parliament of Canada. In economic policy, the free-market was largely derided as a wealth-creator for Aboriginal peoples. Instead what was offered was deemed more appropriate for the different cultural traditions of Aboriginals, a collectivist kind of economic model much in vogue in the 1960s among African development theorists, Third World advocates and Marxist economists. It would operate on a different set of assumptions about how to organize an economy from what prevailed in the “other” society. Settler governments would be obliged to pay past debts, monetarily or culturally, while turning over responsibility for almost everything to Aboriginal governments. The Indian Act, the source of so much woe, was to be eliminated, but not for a while, not until the new parallel governmental structures were put in place. Or the existing ones were fortified with considerable new powers and much new money.

The past was very much with the commission, and not just in the specific sections about history. To put the parallelism in place, it would be necessary for the “settlers” to acknowledge all the wrongs of the past, in the form of, say an inquiry into the taking of Aboriginal children from their homes to be educated in church or state secular schools, and a formal apology offered for that and other conduct. Without using the words, the rest of society had to – as we say in the Christian churches – expiate our sins, or at least those of our ancestors, which involves by definition an acceptance of guilt of the inter-generational kind which, as public opinion surveys constantly reveal, is often not always welcome by those who played no part in the evils of yesterday.

As the great political scientist Alan Cairns wrote after reading the 2,000 pages, it was striking how little attention the commission paid to what Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals have had, or might have, in common as “citizens” within the same state. His preferred conception for these relations was for Aboriginals to be “citizens plus,” a recognition of their historic place and rights blended with an acceptance of shared citizenship with attendant rights and responsibilities; or to put matters another way, the country needed to think through an effort to blend Aboriginal distinctiveness and cultural traditions with mainstream society, rather than to concentrate on what the two groups did not have, and likely would not have, in common. Then, as now, I believe the royal commission would have served a great purpose if it had gone down that intellectual path rather than the one it chose – a path that we are still on and will be for some time. That path was not taken; it was never offered.

The commission had some practical impact. We have had apologies for the residential schools from the governments of Jean Chrétien and Stephen Harper. We now have a commission looking into that chapter of the past. Generally speaking, however, the Dussault-Erasmus commission for all its length had little effect – except in one important respect. Most of the practical recommendations died from neglect or implausibility, but its conception of the future relations between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals based on institutionalized parallelism both reflected and deepened that conception that is now the prevailing one through Aboriginal Canada, among Aboriginals lawyers and law professors, in certain government policies, in constitutional provisions, and in rulings by the Supreme Court of Canada. And we are struggling to give meaning to this idea on the ground, for reasons that might in some quarters be grounded in racism, but also, because the majority of the general public already thinks enough time and effort is being spent on Aboriginals, and because courts have been moving the yardsticks down the field in the Aboriginals’ favour. The parallelism idea on the ground is hard to put into practice for many reasons, not least of which are the demographic realities of many – not all but many – Aboriginal people.

When non-Aboriginals first arrived in Canada, they huddled in small settlements, greatly out-numbered by Aboriginals. Many of them would not have survived had it not been for Aboriginal knowledge and help. But they did survive, and many centuries later it is the Aboriginals who are in a small minority of the population – at a maximum 4 per cent by the most elastic count as to who is a Native Canadian: Inuit, Métis and status and non-status Indian, although in Manitoba and Saskatchewan the Aboriginal share of the total provincial population is heading towards 15 per cent. Unlike many other parts of Canada, the Aboriginal presence is not only rural but decidedly urban, as any walk through disadvantaged parts of Winnipeg, Regina and Saskatoon will show.

Statistics Canada told us, following its 2006 survey, that there were 612 bands and more than 2,600 reserves. People have been voting with their feet, as they say, since Stats Can estimates that only 40 per cent of First Nations people live on reserve, a share that has been slowly dropping for some time. More than 60 per cent of these bands – or “nations” as they choose to call themselves – have fewer than 1,000 people. A handful have populations of tens of thousands such as the Cree in Northern Quebec, or the Dene (Georges Erasmus’ nation in the NWT) but most have fewer than 2,500 people.

As for the economic and social statistics, these are well-known. Unemployment is higher than the national average; on reserves much higher still. Aboriginal educational attainment is much lower, although graduation rates have improved. Half the child welfare cases in Canada are Aboriginal; the Aboriginal prison population vastly exceeds its share of the total population. Sexual abuse, fetal alcohol syndrome, diseases related to obesity such as diabetes, are much higher than the national norm. Suicide rates are higher; life expectancy lower. Some indices have improved, it must be said, but the gaps are a stain on the country. Under these trying circumstances, combined with small numbers, it is hard to find the capacity to run self-governing nations.

Let me illustrate the situation with reference to the recent annual report of the B.C. Treaty Commission. The report lists various First Nations with which final treaty agreements have been signed or implemented. Here are the “approximate” numbers in each “nation”: 2,260, 350, 400, 1,050, 160, 780, 330, 3,460, 290, 225. For those “nations” in “advanced agreements-in-principle negotiations” the numbers are: 770, 940, 465, 550, 1,090, 1,790, 370, 2,505, 1,625, 1,041, 675, 3,685, 5,000 (Haida), 220, 945, 830, 6,565 and so on. But even these numbers misrepresent reality “on the ground.” You will note that the Treaty Commission speaks of “approximately” because it is sometimes difficult for Statistics Canada to get accurate data on reserves, and because a certain number of members of a “nation” do not live in their traditional territories. They have moved away for whatever reason, and although they count as members of the “nation,” they are in absentia. Factor in children and elderly people, a “nation” of 1,000 becomes perhaps 500 or 700 able-bodied adults.

I am not passing judgment here, just presenting a demographic reality that leads to inescapable questions of “capacity,” the ability of small groups of people, often in remote areas, to deliver what is demanded when leaders speak of “self-government.” Because what is “self-government,” commonly understood? It is the capacity of a government, chosen by the people, to deliver services expected in modern societies such as education, health care, roads, social welfare, policing and justice, and other services – all financed, to the greatest extent possible by own-source revenues, for which those in positions of authority, by whatever means, are held accountable.

Given the demographic, it is reasonable to ask whether “nations” of fewer than 1,000 people is an oxymoron. It is certainly a rhetorically powerful idea, but in reality what does it mean? On some reserves I have visited, I have asked myself: Could a group of 500 or 700 PhDs make this territory economically viable and deliver services expected by a self-governing group? Anyone with a smattering of knowledge about university politics must doubt whether the PhDs could effectively govern themselves, but I’m not sure they could do the rest either.

This gap between narrative of self-government and reality, between memory of what once was a long time ago and what is today, reflects what I call the “dream palace” of the Aboriginals – a phrase I adapt from Fouad Ajami’s book, The Dream Palace of the Arabs, about the intellectual and political efforts, especially among Egyptians, to reconcile the greatness of their distant past with their reduced and difficult present circumstances. Inside the “dream palace,” there are today – as there were before, long ago – self-reliant, self-sustaining communities (now called “nations”) with the full panoply of sovereign capacities and the “rights”’ that go with that sovereignty. These “nations” are the descendants of proud ancestors who, centuries ago, spread across certain territories before and for some period thereafter the so-called “settlers” arrived.

Today’s reality, however, is so far removed in actual day-to-day terms from the memories inside the dream palace as to be almost unbearable. The obvious conflict between reality and dream pulls a few Aboriginals to “warrior societies,” others to rejecting the “Crown” or asserting a “nation-to-Crown” legal relationship (that is false except through the government of Canada), others to fight for the restoration of treaty rights and Aboriginal title to create self-governing “nations” whatever their capacity and size, and everyone to demand that government turn over more power and money to Aboriginal “nations.”

The past is omnipresent, although in varying degrees, in the desire to protect “traditional ways,” which in most cases means hunting, fishing and trapping, noble ventures that given the shrivelled markets for these products can lead economically to something only slightly better than subsistence. Without a wage economy beyond these “traditional ways,” the path lies to dependence on money from somewhere else, namely government, which, in turn, contributes, as dependence usually does, to a loss of self-respect, internalized anger, social problems and lassitude.

It is crucial to note here that there are Aboriginal communities that offer the antithesis of this picture. They have – like the Cree of Quebec – a large critical mass of people to organize the delivery of services and they have built a wage economy that brings self-reliance and pride. The Crees have also had exceptionally good leadership from Billy Diamond to Mathew Coon Come. In central Saskatchewan, as in some other resource areas, local Aboriginal people are gainfully employed in natural resource extraction and processing, and in the Saskatchewan case in uranium. In the southern Okanagan, chief Clarence Louie has led a community that is bustling with activity – including a hotel, a golf course and a winery, Aboriginal-owned and-financed – and successful. (Alas, Chief Louie is considered by many other BC Aboriginal leaders as an outcast because of his sharp tongue about their rhetoric and his entrepreneurial drive.) And there are other examples of success. The annual Aboriginal Business Awards pay tribute to some of these successes.

What these successes tend to have in common is that Aboriginal people have decided to integrate in varying degrees with the majority cultures, to form business arrangements in a vital attempt to create own-source revenues that will dilute or end spirals of dependency, especially those with potential natural resource exploitation projects. But even in these areas, there is ambivalence about the desirability of development, either from environmental fears, deep distrust of non-Aboriginal intentions and governments run by non-Aboriginals, uncertainty about the market economy and, most of all, the fears within the dream palace of memory about anything other than a separate, parallel existence leading to assimilation and eventual cultural disappearance.

Parallelism, which is based on old treaties and recent legal developments, has been greatly advanced by court rulings at the provincial and Supreme Court levels, breathing new expression into constitutional protections in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms of 1982. Successive Supreme Court rulings have extended the meaning of Aboriginal claims, rights and title.

The most recent Supreme Court case, William (Tsilhqot’in), involves six bands within a nation with about 3,000 people in a remote part of central BC. It greatly expanded Aboriginal title because it grants the nation Aboriginal title and a de jure veto on any development on their land, except if the government can prove a “pressing and substantial” public interest, which I think will be very hard to demonstrate. The previous Supreme Court ruling, Delgamuukw, had said native title could exist in areas where the band or tribe had settled but not necessarily where it travelled in search of game or fish. William says that if the band has wandered over territory in search of livelihood, and no other band did so, then it has title over all that territory and therefore has a final say over what happens there, subject to the “pressing and substantial” test. Moreover, the court said the statement of Aboriginal claim for title is enough to give the Aboriginal group what I would call a de facto veto, since it must be consulted and “accommodated” over all the land it claims, title having been proven or not.

Every commentator accepts that the ruling strengthens Aboriginals’ legal position and negotiating power, although there is disagreement by how much. BC’s chiefs think they know. At a meeting with Premier Christy Clark, they essentially said the government should recognize Aboriginal title over the entire province’s Crown land and re-start relations from there. Although the ruling was specifically about BC, where there are no modern-day treaties, chiefs across Canada immediately said in various forums that the ruling applies to them, to their title and their rights.

I agree with Jock Finlayson, chief economist of the BC Business Council, who wrote in a balanced summary that, “the full implications of the ruling will only be felt over many years.” I think the ruling greatly complicates any major development in B.C., and will have a long-term depressing effect on the province’s economy.

Others whom I respect are less pessimistic than I am about the ability now to get much done over vast swaths of British Columbia. And of course there are those in the Aboriginal law world who are heralding the decision as an overdue levelling of the playing field between Aboriginal “nations” and governments. For them, this reinforces the parallelism on which they hope the future will be based. I urge people to read my friend, someone I admire very much, emeritus professor Peter Russell of the University of Toronto who offers a quite different interpretation than mine in that he feels the William case represents “a major victory not only for Aboriginal peoples in Canada and elsewhere, but for all people who look forward to a just and mutually beneficial relationship with Indigenous peoples.”

As I said, time will tell. I hope I am wrong. Another person whom I admire, who works with First Nations in BC, thinks I am. In his view, the younger chiefs there want to do business. They recognize their societies are too often stagnating economically. This decision will give them confidence and clarity to negotiate fair deals for their peoples. I think this is the wish being the father of the thought, but again, we shall see.

Parallelism plays itself out in all aspects now of relations between Aboriginal communities and governments and the rest of society. It certainly extends to education, which has been much in the news, with Aboriginals demanding full control of the education systems for their children. Ironically, studies by Professor John Richards of Simon Fraser University demonstrate that Aboriginal students achieve better outcomes in the public school system than in those run by native administrations.

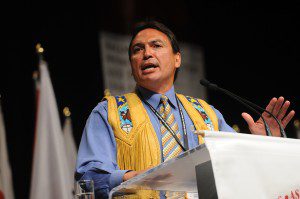

But it has repeatedly been asserted that even if that result were true, the reason lies in inadequate funding for on-reserve schools. Last year, Prime Minister Stephen Harper swept aside his Aboriginal Affairs minister – as often happens with ministers in this government – and negotiated mano-a-mano with the then-national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Shawn Atleo. In these negotiations, the federal government dramatically improved previous offers of money and Aboriginal control and administration.

The agreement, as you will recall, collapsed because Atleo resigned following internal dissent within the AFN, which itself then collapsed. Quite absurdly, the dissident chiefs demanded that the government negotiate individually with each “nation” – all 612 of them. A more sure-fire recipe for inaction could scarcely be imaged. As it is, the old AFN is dead. A leadership contest for a new AFN put Perry Bellegarde in the top job. He will still have one of Canada’s most impossible jobs with 612 bosses. The recriminations that accompanied the AFN’s collapse, and the criticisms heaped on Atleo unfortunately demonstrated the tendency of some Aboriginal leaders, ones who get a lot of media attention, to ratchet up demands to the patently unreasonable, then blame whichever government is in power for failing to accept these demands.

To put matters more bluntly, with these sorts of demands, and this sort of negotiating structure, it is hard to get a Yes, because agreement would have offended the political culture of opposition that too many Aboriginal leaders have created and propagated. And if you think I exaggerate, take a look at the history of the BC Treaty process that started when Brian Mulroney was prime minister and Mike Harcourt was premier. In all those years, there have been six – count them six – implementing treaty agreements, and three completed final agreements out of 65 First Nations representing 104 Indian bands. At this crawling pace, the youngest person reading this article will be dead before treaties are implemented. But of course that isn’t true really because 40 per cent of the First Nations in BC never entered the negotiating process or dropped out, some of them because they do not recognize the authority of the Crown. What began with high hopes for reconciliation through treaties that would enshrine the parallelism inherent in treaties and self-government by nations has been an almost complete failure – with blame on both sides to be sure, and Aboriginals saddled with hundreds of millions of dollars in debt through negotiations, monies they were to have paid off through the cash components of the settlements. A cynic would say – and there is plenty of room for cynicism here – that the biggest victors in this BC process have been the Aboriginal lawyers.

It is not popular, I know, to say some of this. There is a great deal of touchiness around these matters, but I started writing about Aboriginal issues when no one in the Ottawa bureau wanted to do so back in the late 1970s. I am hardly an expert, merely an observer, and wrong though I often am, and have been, I am not impressed by rhetoric from government or any other group, nor am I worried about the consequences of stating what I consider to be home truths. Anyone willing to write a book saying that the emperor of Canadian health care was wearing tattered clothes does not shy from offending shibboleths, although I never seek to do so in an insulting or derogatory fashion.

It took non-Aboriginals a tragically long time to realize that subjugation and assimilation was morally wrong and could never work. We had a lot of learning to do, and we have a lot more to do. We are now embarked on a new path that, with the greatest respect, I do not think is going to work very well, some of the reasons for which I tried to explain here. There is a middle ground about which little thought has been given of accommodating difference without entrenched parallelism, of “citizens first,” of emphasizing what we have in common, and what we owe each other as common citizens of a great country that has surmounted many obstacles. And while we must never forget the past, and while in this complicated relationship it will never be past, it should not guide us into the future if we are to make the kind of progress we need and want.

Jeffrey Simpson is the national affairs columnist for the Globe and Mail. This article is based on his prepared remarks for the F.R. Scott Lecture at McGill University in October 2014.