Canada, like other democracies, should state its strong disapproval of Hong Kong’s move against a reputable media organization, and work with likeminded partners in providing assistance—and political asylum, if necessary—to those who are now targeted by this new white terror, writes J. Michael Cole.

Canada, like other democracies, should state its strong disapproval of Hong Kong’s move against a reputable media organization, and work with likeminded partners in providing assistance—and political asylum, if necessary—to those who are now targeted by this new white terror, writes J. Michael Cole.

By J. Michael Cole, August 10, 2020

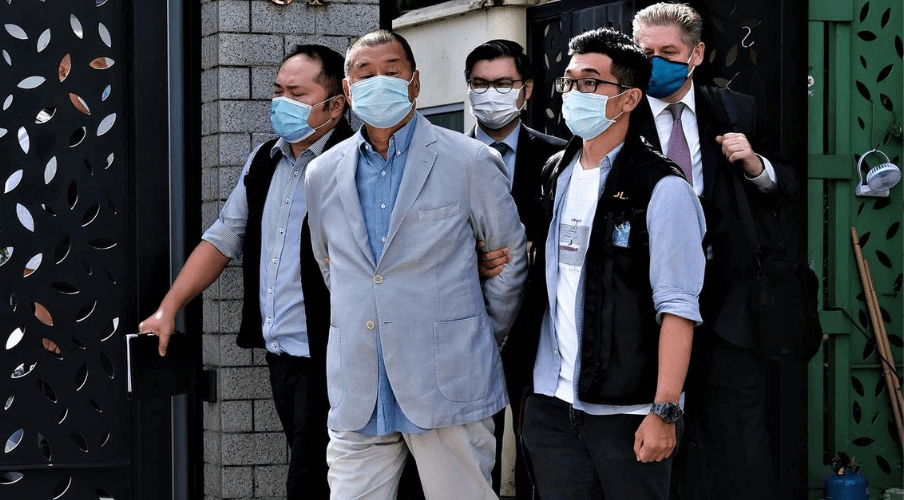

Early in the morning of August 10, officers from a new police unit created to enforce the new National Security Law imposed by Beijing on the former special administrative region of Hong Kong took Jimmy Lai, owner of the Apple Daily newspaper, into custody. Within hours, his two sons, as well as senior management at Next Digital, were also taken into custody. As the arrests took place, a large contingent of police officers raided Apple Daily’s headquarters in the city. Lai’s right-hand man, Mark Simon, who is reportedly abroad at the moment, has also been put on a wanted list.

Sources told the South China Morning Post that Lai was arrested for “collusion with a foreign country, uttering seditious words, and conspiracy to defraud.” This was the third wave of arrests since the new law came into force on June 30. Besides the arrests, six Hong Kong individuals who are currently abroad have been placed on a Wanted-for-Arrest list.

Lai doesn’t fit the description of the type of individual whom, Hong Kong authorities assured us, were to be targeted by the new law—a “handful” of teenagers who “threatened stability” in the city. Instead, Lai, along with the senior management at his media empire, headed one of the very few remaining media in Hong Kong that, in recent years, have continued to criticize government policy and the Chinese Communist Party.

The arrests undoubtedly are meant to send a strong message to any would-be critic of the CCP and its lackeys in Hong Kong, and could very well spell the demise of Apple Daily in the city (the newspaper and its television network are also present in Taiwan, which is rapidly turning into the last bastion of free speech in the “Greater China” area). No doubt Lai, who travelled frequently, was also targeted because of his ability to speak truth to power, at home and abroad. He was, beyond doubt, a thorn in the CCP’s side.

If there was any doubt about the reach of the new national security law, this is it: nobody is safe. Indeed, even at the time of writing this article, pro-democracy leader Agnes Chow was put under arrest. And we can expect that other senior figures in the pro-democracy camp will be taken into custody in the days and weeks to come. Even speaking to foreign reporters—who in recent months have found it increasingly difficult to obtain work visas to remain in the city—or foreign NGOs, many of which are now looking to relocate elsewhere in the region, could now lead one to be accused of “collusion with a foreign country.”

In a matter of weeks, Beijing has succeeded in completely co-opting the pro-establishment camp and elites across the territory: media, large corporations, banks and universities have all gone silent, or have become complicit in what can only be described as a hostile takeover.

At this point, we do not know what fate awaits Lai and others who have been taken away under the new law, whether they will be tried in Hong Kong courts or be spirited into the Kafkaesque “legal system” in the Mainland. What is certain is that most are facing years—and in some cases a lifetime—of imprisonment, conceivably without any possibility of bail.

Today’s move makes it clear that China’s experiment with a more liberal special administrative region is over. Hong Kong now serves as the opposite example to the rest of China, a demonstration of its intolerance for any challenge to the CCP’s will, and an example, to the rest of China, of the unruliness and “chaos” that such (“Western”) freedoms supposedly engender. Gradualism is over; now, in one fell swoop, the charade has ended, and with it the possibility that Hong Kong could serve as an example of a possible future China, one that is more open, more liberal, and perhaps even democratic. Those dreams, for the time being, are no more.

Lai’s arrest doesn’t exactly come as a surprise. Beijing has long regarded him as the mastermind of an alleged conspiracy (comprising “foreign elements” which inevitably are part of such constructs by closed political systems) to cause instability in Hong Kong. Those suspicions had already led to harassment and physical attacks against Lai and his media. His arrest is nevertheless proof that international opprobrium, as well as US sanctions, such as those announced last week under the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, have had little, if any, deterring effect on the willingness of the CCP and Hong Kong authorities to silence dissent and skewer the pro-democracy movement. In fact, it is possible that this escalatory move is in retaliation for international responses.

If that is indeed the case, then the international community must take a close, second look at its strategy to influence decision making in Hong Kong and Beijing, and find other vectors by which to hit those responsible where it hurts the most. Canada, like other democracies, should state its strong disapproval of Hong Kong’s move against a reputable media organization, and work with likeminded partners in providing assistance—and political asylum, if necessary—to those who are now targeted by this new white terror.

J. Michael Cole is a Taipei-based senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, the Global Taiwan Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Taiwan Studies Programme at the University of Nottingham. He is a former analyst with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service in Ottawa. His latest book, Insidious Power: How China Undermines Global Democracy, co-edited with Dr. Hsu Szu-chien, was published in July.