This article originally appeared in the Financial Post.

By Shawn Whatley, January 25, 2023

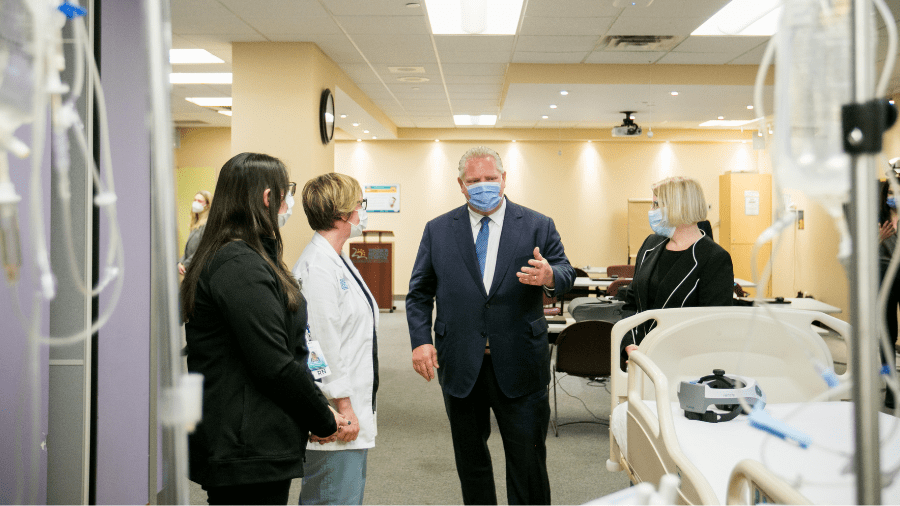

Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s new health-care plan has caused serious alarm in some circles. In part, the problem was his mentioning “private” in the same sentence as “health care.” Cue the histrionic headlines about “private care” and “for-profit” health care.

But the headlines were misleading. As the premier himself emphasized, “Ontarians will always access health care with their OHIP card, never their credit card.”

The real cause for alarm lies deeper. Ford’s plan disrupts hospitals by shifting services, such as MRIs, CT scans, and hip or knee replacements, to smaller, more innovative facilities. Non-hospital facilities are far simpler than hospitals. They have fewer restrictions and, unlike hospitals, they get paid for what they produce, not because they exist.

Harvard business professor Clay Christensen, who died in 2020, was famous for 1997’s The Innovator’s Dilemma, which he based on his research about disruptive innovation. Consider how mainframe computers once dominated computing. Mainframes changed slowly, following a low-sloped trajectory. Personal computers entered the market as a novelty and no threat to mainframes — apparently. But the little computers followed a steep-change trajectory and soon shot past mainframes by offering quality computing at a fraction of the cost. Ontario’s new plan is classic Christensen: smaller, leaner, more agile operations are going to shoot past behemoth hospitals.

But why disrupt rather than try to change the hospitals themselves? Hospital services are trapped in a trilemma. Provinces cannot compromise the standard of care in hospitals, doing so would be unethical. They can only adjust wait times or costs. Shorter waits mean higher costs; spending cuts mean longer waits.

The trap stems, in part, from our love of “global” hospital budgets, in which hospitals receive a fixed, annual budget to cover all the anticipated needs in the community served by the hospital. Global budgets are simple to administer and predictable to plan. But simplicity and predictability come at the expense of rigidity and resistance to change. Hospital processes are built to resist change, no matter how many patients stand in line for no matter how long waiting for care.

Quebec and Ontario now have almost two decades’ experience with non-global hospital funding, mostly variations on activity-based funding (ABF). When paid per procedure, hospitals do find ways to adapt and deliver more care at a lower cost. ABF drives hospitals to increase outputs using fewer inputs. But ministers of health struggle to get hospitals to co-operate. ABF is not perfect, and hospitals are motivated to find — and exploit — all the ways it can fail. Over the years, the resisters have prevailed.

Ontario introduced pay for results in 2008: the “P4R Emergency Department Wait-time Strategy.” Some hospitals jumped to beat benchmarks (and neighbouring hospitals). They transformed emergency services. Other hospitals just complained and refused to try.

In 2012, the province tried to change the entire hospital funding system. Health System Funding Reform introduced Quality-Based Procedures — detailed cookbooks on ideal treatment. As expected, “quality” hijacked service. Staff focused on quality cookbooks, not efficiency or wait times.

None of these attempts (nor others) created major change in hospital management or services. Doug Ford knows this. Public hospitals seem immune to change.

Ontario already has Independent Health Facilities. These publicly funded, privately owned facilities provide diagnostic imaging, sleep studies, dialysis, abortions, minor surgeries and more. There were over 800 IHFs in Ontario in 2012, 50 per cent physician-owned. For example, a clinical pathologist, who owns a lab, could bill for all the tests done. Or a radiologist might read all the scans performed at a radiology suite, billing for each one. More often, a group of physicians would work together to manage all the work created in a particular lab or imaging facility. Ownership structures could vary: partnerships, associates, sub-contractors, and so on.

IHFs get paid for services provided. If output slips, income suffers. High-quality care is essential to maintaining licensure and market share. Patients can choose which IHF to use. Any hint of unfriendly service, long waits or doubts about quality drives patients away. Unlike hospitals, IHFs must remain acutely sensitive to service, quality and wait times.

In essence, the new Ontario initiative simply allows for IHFs (or something similar) in a wider range of investigations and surgeries. If it succeeds — and given its incremental nature it’s hard to see why it wouldn’t — it will have achieved a significant innovative disruption to the status quo.

The premier’s plan is “bold” because it disrupts. It gives services traditionally “owned” by the hospitals to facilities that must innovate to stay solvent. By introducing competition into the supply of these services, it is bound to be good for patients. Anyone who cares about health care should hope Ontario gets its new plan up and running soon.

Shawn Whatley is a practicing physician, a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, and author of When Politics Comes Before Patients: Why and How Canadian Medicare is Failing, 2020.