Spending in this budget is not concentrated in specific areas where government can make a difference, but spread far and wide so it has little impact outside of the bureaucracy, writes Philip Cross.

Spending in this budget is not concentrated in specific areas where government can make a difference, but spread far and wide so it has little impact outside of the bureaucracy, writes Philip Cross.

By Philip Cross, March 20, 2019

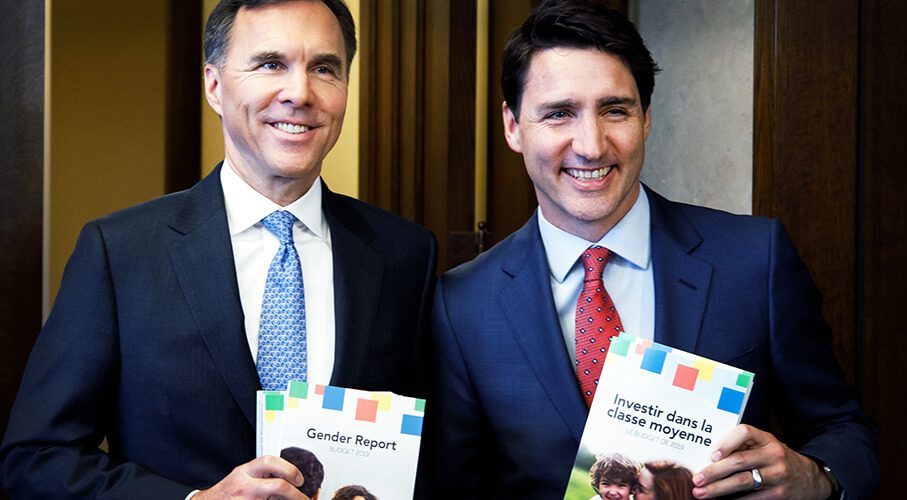

For his fourth budget, Finance Minister Bill Morneau carefully selected the symbolism of recycling his shoes from a retrained worker rather than the traditional purchase of a new pair. Refurbishing his shoes is more a homage to how this government has recycled the same commitment to deficit-financed increases in spending through every one of its budgets. The result has been the largest increase in government spending of any administration since the 1980s outside of recessions.

The Liberal government has displayed an unwavering belief in the virtues of more government spending, possibly because it requires no ethical commitment higher than a mendacity about returning to a balanced budget. The tone was set before Prime Minister Justin Trudeau took office when he mused that “the budget will balance itself” through economic growth. When Ronald Reagan professed a similar faith in the magical ability of government stimulus to pay for itself, he was ridiculed for voodoo economics, but Trudeau’s version passed largely unquestioned. The election campaign reinforced the spend more reflex, as the Liberal tactic of promising everything to everyone was rewarded with a majority government.

Inheriting a weak economy upon taking office, the mantra of the Trudeau government’s first budget was the need to spend more to prime the economy’s pump. When the economy eventually did pick up in 2017 thanks to faster growth in China and the U.S., the government spent all the windfall of extra revenues. Now that the economy is slowing again, the automatic solution is even more spending.

Reflexive higher spending is now reinforced by the political imperatives of distracting the public from the SNC-Lavalin scandal and firming up the electoral support of its base (although the next election year budget to affect an electoral outcome will also be the first). The end result is that during Trudeau’s tenure, government spending has increased 20 per cent, from $296.6 billion to $355.6 billion.

However,the largest spending increases were direct program expenses from running a government not vote-buying transfers to people or lower levels of government. Cost overruns like the Phoenix pay system fiasco are unpopular with both taxpayers and bureaucrats, yet have become the new normal in today’s government operations.

The grape-shot approach to government spending is reflected in the budget document itself. It expanded from 269 to 460 pages over the last four years. At the same time, government spending programs are no longer concentrated in specific areas like the Canada Child Benefit where government can make a difference, but spread far and wide so it has little impact outside of the bureaucracy needed to implement them.

Liberal faith in government spending does not extend to financing it on a sustainable basis with taxes. While the looming election rules out tax hikes, if they really believed their own rhetoric that consumption taxes like the one on carbon are the most efficient, they would have shifted the mix of taxes from incomes to the GST, the Holy Grail for economists who argue this creates the most efficient tax system.

Instead, the government has increasingly backpedalled from tax measures to raise revenues. Its election platform intended to pay for a middle class tax cut with higher taxes on the richest Canadians, but the Department of Finance proved this would not work — high-income people would either avoid taxes or work less. Then in 2017 the government rolled out its disastrous plan to raise taxes on many small businesses, a naive academic idea that crashed on the rocks of business tax planning reality. Instead of raising revenue, this initiative ended up costing money when tax rates were cut to quell the uproar in the small business community. More tax incentives for business investment were made last fall when the government realized it was imperative to restore Canada’s competitiveness after U.S. President Donald Trump’s aggressive cuts to the corporate income tax.

The combination of a growing reliance on more spending and a trepidation about raising taxes inevitably meant higher deficits. This is why the government quickly tossed aside its pledge to limit deficits to $10 billion and balance the budget by 2019.

What does Canada have to show for all this spending and deficits? Certainly not faster economic growth. Since 2015, real GDP growth in Canada has averaged 1.9 percent, less than in the previous four years while the budget itself forecasts falling growth in 2019. Slower growth during the Trudeau years occurred despite much larger doses of both monetary and fiscal stimulus; on top of the federal government’s large and sustained budget deficits, the Bank of Canada lowered interest rates and presided over a devaluation of the loonie.

One lasting effect of Canada’s increasing dollops of stimulus was a surge in housing prices in Vancouver and Toronto, which required a tightening of mortgage regulations to curb possible housing market bubbles. The government is now trying to shield some young people from the effect of this tightening; in the unlikely event it succeeds, housing demand will ramp up again, requiring other policies to cool the housing market. This is how governments become mired in a web of often contradictory regulations.

The end result is an economy that looks largely as it was four years ago, except with higher government spending, persistent budget deficits and more stringent housing regulations. Economic growth is sputtering, oil prices are low, no pipelines have been built to access markets outside the U.S., manufacturing remains moribund, business investment has faltered, export competitiveness has eroded, and the federal and most provincial governments remain at each other’s throats. This stasis is hardly the “Real Change” promised by the Liberal 2015 election slogan.

Philip Cross is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute