Canada’s world-class energy resources and national interests in global energy diplomacy must be articulated coherently and to the fullest, write Henry Geraedts and Shuvaloy Majumdar.

Canada’s world-class energy resources and national interests in global energy diplomacy must be articulated coherently and to the fullest, write Henry Geraedts and Shuvaloy Majumdar.

By Henry Geraedts and Shuvaloy Majumdar, November 27, 2020

Economic diplomacy forms the vast majority of international relations, where issues of war and prosperity are often defined by the geopolitics of energy. In far too many quarters of Canadian national life, political correctness and climate extremism have subversively undermined both an understanding of the realities of energy diplomacy, and the capacity for Canada to realize its vital national interests.

In the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (then-OAPEC) imposed a retributive oil embargo that catalyzed global oil shocks. Formed through informal conversations in the corridors of the wider transatlantic alliance in response to this economic fallout, the G7 conceived its mandate as the economic steward of the world’s major market democracies, providing a forum for economic resilience throughout disruptions. Their statecraft was essential in stabilizing recovery following the Great Recession of 2008-2009.

A half-century later, a global pandemic has shuttered the international economy, and the global oil cartel (now-OPEC) is being tested to provide both price and supply stability. Meanwhile, the Indo-Pacific region’s emergence as the hub for global growth in the decades to come is dramatically rebalancing international relations.

On this stage, China’s President Xi Jinping emerged on November 19th at the virtual version of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO Dialogues, hosted by Malaysia. True to current form, despite Canada’s status as a founder of APEC, no Canadian federal minister was present to advance our own economic diplomacy in the face of the far-reaching implications of Xi’s “Dual Circulation” doctrine.

On October 29th, 2020, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) finalized its 14th Five-Year Plan. Of critical importance, it enshrined Xi Jinping’s “Dual Circulation” framework for turning China into an advanced economy, doubling the size of its economy by 2035 and overtaking the United States.

“Dual Circulation takes domestic circulation as the main body, with domestic and international circulation reinforcing each other,” reads the CPP script. Stripped of its jargon, “Dual Circulation” codifies an inward turn and has the pre-Deng Xiaoping hallmark of economic self-sufficiency, improbably predicated on achieving independence in technology, food and energy, so as to insulate China’s persistent vulnerabilities from geopolitical impacts while expanding its presence on the global stage. In short, Xi’s strategy is to decouple the Chinese economy from its export-driven mode to an increasingly self-reliant domestic one. Arguably, this was always the CCP’s plan for a rising and reinvigorated Middle Kingdom.

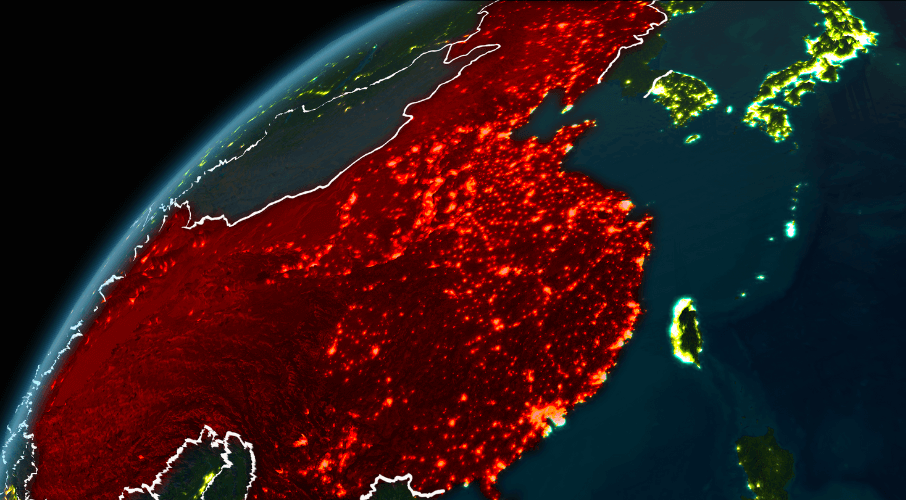

Yet, while Xi might hope to minimize China’s vulnerability when it comes to its reliance on global energy supplies, the truth of the matter is that there is almost no chance that such energy autarchy will succeed. For perspective, with 25 percent of global totals, China is the world’s top energy consumer and largest oil and gas importer. Remarkably, it continues to burn more coal than the rest of the world combined. Even China’s inroads using its Belt and Road Initiative from Central Asia into Europe, long-term deals with Iran and Pakistan, and key energy purchases in Africa, Asia and Latin America show that, while eager to minimize its vulnerability to dubious energy suppliers, it will remain dependent on external energy markets for the foreseeable future.

China’s energy realities should also be viewed against even larger global trends. Abundant hydrocarbon energy sources are expected to power economies around the world for decades, quite conceivably well beyond mid-century. This observation runs counter to the prevailing political and public climate narrative; it is, however, based on international data and unrelenting market dynamics. International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts indicate that from 80 percent today, hydrocarbons will continue to account for 75 percent of total primary energy demand in 2040, and that even if all Paris Accord signatories actually fulfilled their commitments, hydrocarbons would still account for 60 percent by then.

Low energy density, intermittency, high life cycle costs and a negative environmental footprint mark wind and solar as unsustainable long-term components of any energy transition. After 20 years and an estimated US$2 trillion invested, wind and solar in 2019 represented a stagnant 2 percent proportion of global energy output. Expectations of Moore’s Law for leaps in battery and hydrogen technologies are not grounded in reality.

The bottom line is that other than a massive and concerted global nuclear power strategy, enabling the integrated electrification of key sectors of our societies and the industrial development of the Indo-Pacific and Africa, there are at present no credible alternatives to hydrocarbons as the primary source of affordable energy. The overarching reason for why hydrocarbons will remain indispensable, is the interlocking hydrocarbon-based technology systems that are immutably woven into every segment of our societies at global scale.

Canada has been without a comprehensive foreign policy framework for nearly two decades, leaving us without relevant policies to address the rapid changes in the Indo-Pacific and China, including an actionable framework for articulating Canada’s world-class energy endowment as a multi-pronged foreign policy asset. The Trudeau government’s deliberate mismanagement of our most important natural resource is a case study of messianic ideology mired in incompatible and unaffordable objectives, unconstrained by economic and physical realities.

Canada’s 21st century prosperity will in large part depend on how we engage key actors in the Indo-Pacific, and in particular China. The region represents 50 percent of the world’s population and is expected to drive demand for hydrocarbon energy into at least mid-century. China’s efforts to reduce its energy vulnerability does not change that unalterable fact. The region’s dynamics are precipitating a global shift in socio-economic wealth unique in modern history and will define international security for decades to come.

The Indo-Pacific is home to many critical shipping routes, and energy security is of acute concern. Chinese-Russian gas interests have intensified, with landmark “Power of Siberia” pipeline agreements connecting the Russian far east with China’s north, and Western Siberia to Xinjiang. The United States is becoming a key supplier of both LNG and oil – including Canadian crude exported via the US – while Australia has overtaken Qatar as the largest exporter of LNG to the region.

Canada, endowed with the world’s 3rd largest oil reserves, 4th largest LNG producer (partnered with South Korean and Japanese investment), 2nd largest uranium producer, and source of some the most advanced and environmentally capable energy technologies, is for all practical purposes absent from this vital arena.

In this, the following three fundamentals should inform how Canada articulates its energy interests in the Indo-Pacific:

- First and foremost, pursue nation-building at home and resolve the energy-related national unity crisis. Federal and provincial governments must enforce their legal powers to ensure timely completion of both TMX and Coastal GasLink LNG pipelines, providing access to Pacific tidewater for Western Canadian hydrocarbons.This requires addressing disastrous regulatory capriciousness that has caused profound damage to Canada’s reputation and credibility, particularly for investment. As part of owning Canadian access to trans-Pacific energy markets, the federal government must repeal the brutally discriminatory Bill C-48 as part of a robust policy framework to attract new, in particular Indigenous, domestic and foreign investment, in second-generation tidewater pipeline projects.

- Second, deploy a comprehensive Canadian energy action plan that supports the Canadian social safety net. The federal government must implement an integrated foreign policy framework of actionable trade, energy and regional security objectives, enabling Canada to establish itself as an indispensable actor in the Indo-Pacific, with direct benefits to the prosperity and quality of life for all Canadians. Membership in the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership is one necessary, but insufficient, component of such a foreign policy framework.Canadian energy assets and energy technology capabilities represent a valuable, multi-faceted strategic foreign policy tool. Nations in the Indo-Pacific can be expected to welcome access to environmentally superior and secure sources of traditional energy that are accessible across an undisputed Pacific Ocean. As a result, Canadian energy supplies would represent an important contribution to overall regional security, energy security and source diversification, enabling a critical transition for a lower carbon economy, replacing coal with LNG.

- Third, build real leverage. Norway clearly articulates the influence its energy affords, right in the mission statement of its Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The proposition of a reliable Canadian energy supply to the region, including to China, can provide Canada with a magnitude of sorely needed leverage that is completely absent today. Despite its attempt at achieving some level of autarchy through Dual Circulation, China will remain highly dependent on external energy supplies, even as its focus shifts to supplies that have lessened geopolitical risk – and that option must include Canada. A Canadian proposition would empower a serious Canadian voice in negotiations across a spectrum of bilateral issues. Gaining this leverage has been willfully ignored by the federal government thus far, neglecting China’s proven record of respecting strength, while exploiting weakness.

In the age of decoupling, competition for the norms and rules governing the Indo-Pacific region’s prosperity, shaped by starkly competing energy interests, will have a profound impact on Canada’s economic and political standing in the world, including for quality Canadian jobs, investment attractiveness and strategic partnerships.

As one thought leader has termed, Canada must become an active participant as a rule-maker, instead of remaining a rule-taker. In order to achieve this, our world-class energy resources and national interests in global energy diplomacy must be articulated coherently and to the fullest.

Henry Geraedts holds a PhD in International Political Economy and is a long time China observer. He is an Adjunct Professor with the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy at the University of Saskatchewan. Shuvaloy Majumdar is Program Director and Munk Senior Fellow for Foreign Policy at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.