This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Shawn Whatley, January 23, 2023

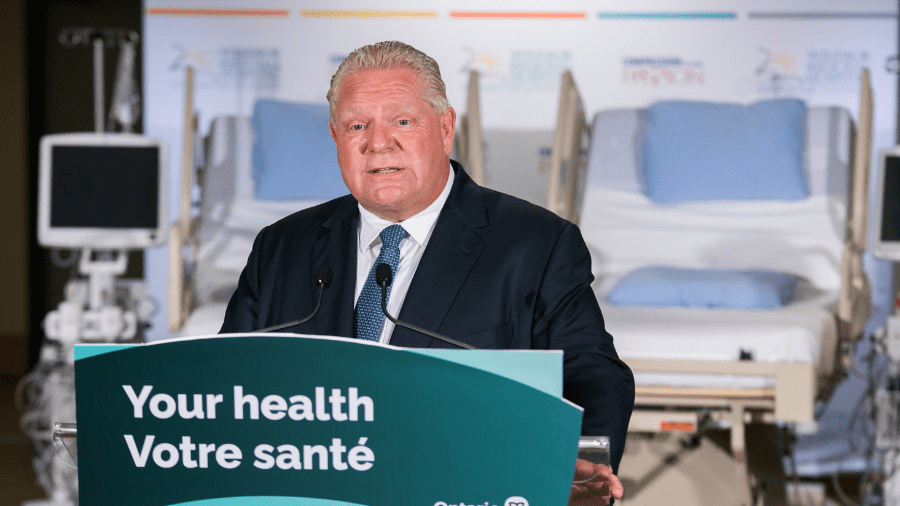

Last week, Ontario Premier Doug Ford announced his three-step plan to increase health services in the province. Patients will soon have access to many more minor surgeries, MRIs and CT scans outside of hospitals. By 2024, patients can expect hip and knee replacements offered in non-hospital facilities, as well.

However, Ford’s announcement may have created more anxiety than the Progressive Conservatives expected. Shorter waits and more convenient access to care are good for patients, but scary for the industry. The changes risk making winners and losers in a zero-sum funding game.

“We need to be bold. We need to be innovative. We need to be creative,” Ford said at a news conference, adding that Ontario needs to look at “other provinces and countries” and “borrow the best ideas.”

Using the word “bold” in the same breath as “innovative” and “creative” almost guarantees anxious apoplexy in Canada, even for the patients who could benefit from such changes.

“We also need to be clear: Ontarians will always access health care with their OHIP card, never their credit card,” Ford said.

It seems he was not clear enough. Headlines such as, Ontario Releases Plan to Invest in Private Health Care, competed with news reports about “for-profit” and “private clinics.” Many people seemed to have missed the point.

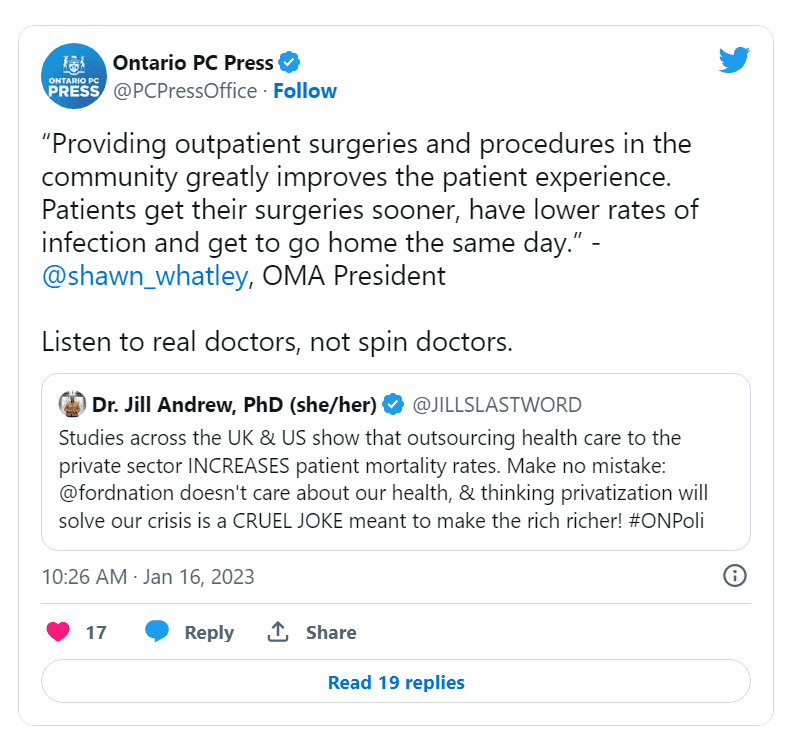

Twitter amplified the negative. An Ontario NDP MPP said Ford’s use of “the private sector” was a “cruel joke,” which prompted the Ontario Progressive Conservative Press Office to tweet back the following quote from me in its defence: “Providing outpatient surgeries and procedures in the community greatly improves the patient experience. Patients get their surgeries sooner, have lower rates of infection and get to go home the same day.”

Perhaps the reason why so many people felt compelled to attack, despite Ford’s emphasis on public funding, was because they are used to our hospital-centric health-care system. Hospitals used to be the only place to get care: practically every surgery, procedure, X-Ray and lab test was done in a hospital. Admitting patients for investigations, not just treatment, was common until the early 2000s.

Perhaps the reason why so many people felt compelled to attack, despite Ford’s emphasis on public funding, was because they are used to our hospital-centric health-care system. Hospitals used to be the only place to get care: practically every surgery, procedure, X-Ray and lab test was done in a hospital. Admitting patients for investigations, not just treatment, was common until the early 2000s.

Most Ontario hospitals are incorporated, not-for-profit entities. They rely on government funding for operational expenses but can raise funds through charitable donations to cover capital costs. (One private surgical hospital remains in Ontario: the Shouldice Clinic.)

In 1990, Ontario started to break free from hospitals with the implementation of independent health facilities (IHFs), which provide diagnostic imaging, sleep studies, dialysis, abortions, minor surgeries and more. By 2012, the auditor general reported that there were over 800 IHFs in Ontario: 50 per cent were physician owned, and 25 focused on minor procedures. They are “private” in the same way many family doctors’ offices are privately owned.

The move away from hospital-centric care continued in Ontario throughout the 1990s. The province cut hospital beds from 33,403 in 1990 to 18,781 by 2003. Hospitals decreased admission rates, shortened lengths of stays and shifted to outpatient care.

Ambulatory day surgery had shown promise as early as the 1890s, but only became common in the 1970s. By 2011, Ontario hospitals used day surgery for 40 per cent of procedures, but the procedures themselves were still performed in house.

Premier Ford’s plan is bold because it breaks the status quo, not because it breaks new medical ground. It weakens the corporatist-style iron triangle that exists between government, doctors and unions, which ensures that each party holds a veto over policy, thus maintaining the status quo unless all parties benefit.

Expanding services outside hospitals upsets the whole triangle. IHFs can innovate to meet patient needs without the restrictive layers of bureaucracy found in hospitals. Indeed, IHFs must deliver quality care and services, while finding efficiencies at the same time. If not, they go broke. Hospitals, on the other hand, never feel the same pressure to produce.

Ford’s plan threatens union hegemony, as well, by allowing staff to work outside a unionized environment, at least in the short term. Expansion also upsets the regulatory apparatus, which currently utilizes public hospitals for surgeries, not IHFs.

Finally, Ford’s plan disrupts physician pay scales. Expanding services promises big raises for doctors who perform procedures. Hospitals limit operating room time to save money, which limits surgeons’ income. Expanding surgery outside hospitals means surgeons can spend more time operating, which generates more income than office work. However, proceduralists already make more than other doctors, who cannot ramp up services easily. Ford’s plan will widen the pay gap and stoke envy.

Disruption aside, Ford’s plan sounds good for patients. We should have done this decades ago. But it will upset the status quo. Someone’s ox will be gored. Let’s hope Ford gets it done before vested interests block the expansion.

Shawn Whatley is a practising physician, senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and author of “When Politics Comes Before Patients: Why and How Canadian Medicare is Failing.”