The unwillingness to address fundamental challenges made the pandemic much worse than it had to be for First Nations across Canada, writes Melissa Mbarki.

The unwillingness to address fundamental challenges made the pandemic much worse than it had to be for First Nations across Canada, writes Melissa Mbarki.

By Melissa Mbarki, March 23, 2021

As the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s COVID Misery Index has revealed, Canada ranks near the bottom among the 15 countries surveyed when it comes to misery arising from the pandemic. Specifically, Canada ranked 11th out of 15 countries on the scale – based on 16 measures that range from the direct impact of the virus (disease misery) to the efficiency of the government’s mitigation efforts (response misery) to the economic consequences of the virus and the government’s response to it (economic misery).

While Canada did not suffer as much disease misery as many of the other countries reviewed, its handling of the pandemic has proven far more costly – from a mitigation perspective (testing, vaccines, etc.) and in terms of economic consequences (debt, job losses, etc.).

Yet this only tells some of the story. Some groups in Canada faced additional challenges that only increased the misery in their communities. A more in-depth look at First Nations’ reserves and their experience with COVID reveals the real-life consequences of this terrible epidemic.

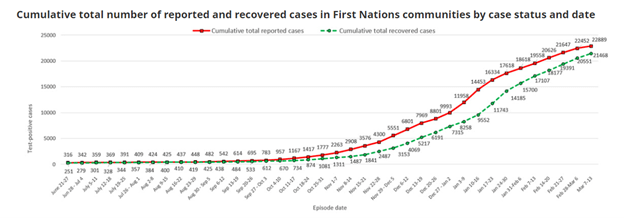

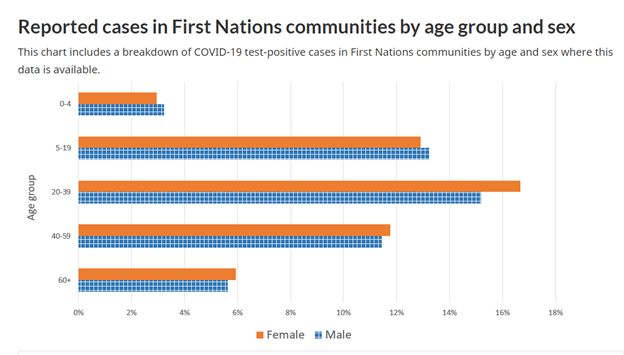

The first wave of COVID-19 had only a limited impact on First Nations, with no more than 500 cases from June to mid-September 2020. Yet this changed with the second wave. From September 2020 to February 2021, First Nations experienced a drastic increase to 22,000 cases. The current third wave is hitting remote Indigenous communities particularly hard. The rapid increase of COVID-19 cases in First Nations are outlined in the following two charts from Indigenous Services Canada.

Socioeconomic inequities make First Nations more vulnerable to infectious diseases than any other community in Canada. This is due to limited access to health care, higher rates of underlying medical conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, economic barriers, isolation, poor housing, seriously overcrowded homes (often in poor repair), and no access to clean water. Other factors that contribute to the rise in numbers include no access to isolation housing, limited health care services (including workers in communities) and access to vaccinations.

Housing, or rather the lack of adequate housing on reserves, has created a cauldron of disease. Social distancing is not an option in multi-family homes. If one family member tests positive, the rest of the household are not able to isolate. In the case of the Eabametoong First Nation, temporary tents and shacks set up for COVID-19 isolation were converted into homes.

Another huge issue is having clean water for drinking and proper sanitization. How can First Nations comply with the basic public health guidelines when proper hand washing is not even possible? Poor water supplies alone makes many communities vulnerable to infectious diseases.

The list of fundamental challenges goes on: lack of food security and poor nutrition, women not having the ability to leave abusive relationships, and profound inequalities in education were exacerbated during the pandemic. Most Canadians take for granted reliable, stable Internet and their ability to use a laptop/tablet for school or work. Indeed, many First Nations communities struggle to provide families with the basic home school set up for their children; and numerous students have now fallen as much as two years behind in their studies during the pandemic.

Even before the pandemic, First Nation communities have been dealing with mental health issues, addictions and family violence. A high-profile police presence in my community was common on the weekends. The short-hand question of “How bad?” really means, “How bad were they beaten or hurt?” or “Will they make it?”

Nearby towns and cities have shelters for women and their families at risk. On the reserve, where shelters are often not an option, a family member’s home is the most likely safe place. The movement of women and children, of course, leads to overcrowding and accounts for some of the multi-family situations evident on reserves.

There is also the isolation imposed by the pandemic and the mental distress generated by it. Many First Nations were challenged by the loss of support systems and threats to family cohesion. Communities could not hold a traditional burial for those who have passed on, nor could people be there to support those who were grieving.

Ceremonies like sweats, feasts or round dances and powwows have been cancelled. These gatherings are integral to our traditions and ceremonies and are far more common, outside the pandemic, than many non-Indigenous people recognize. Losing that interaction has challenged all of us. We have had interactive powwows, but it’s not the same as sitting in an arbor watching the dancers in person.

Many communities decided to isolate members by closing reserve borders to almost all travel. This meant limited access to family members. Personally, I have only seen my family twice last year, though I would normally visit them on holidays and during the summer.

Closing our borders also limited the flow of drugs coming into the reserves. An elder said this may have been the only good thing that came from the pandemic. It is forcing our leaders to look closely at what we need to address this issue in the long-term.

Another benefit of closing the border was that it gave the community back some autonomy to make decisions. They decided when restrictions could be eased or enforced. Our governments distributed food, water, firewood and other supplies to community members. We have been hearing stories of some First Nations abusing this control and not allowing people to leave. We have to remember these enforcements are in place to keep our communities safe and not to control people unduly. But not all First Nations people respect the authorities.

Our elders are worried about the borders opening. Our communities believe that when the floodgates open, we are going to see more drug use and more deaths by overdose. Such fear is well-founded. After all, Statistics Canada released a report that showed an increase in the number of non-COVID-19 deaths because of increased substance use.

We will likely never know the actual number of suicides, drug overdoses or heart attack (health-related) deaths that occurred on reserves during the pandemic. There is no way to track these numbers adequately, particularly when off-reserve populations are taken into account. As a First Nations person, I am always skeptical when the government asks for this data without telling me the reasons why they need it. The long history of under-reporting Indigenous realities continues.

It is critical that we address infrastructure and mental health issues on reserves. Many of these issues were pre-existing prior to and amplified during the pandemic. Government has been complacent for too long and provided bandaid fixes rather than long-term sustainable solutions. First Nations, including my own home community, have suffered a great deal over the past year during this pandemic. It will take years to fully recover.

MLI’s COVID Misery Index shined a much-needed spotlight on the misery generated by the pandemic – including on areas (such as response or economic consequences) that are frequently overlooked. Yet, as this review shows, some communities fared much worse than others in terms of misery. As we look back on 2020-21, we need to realize that the unwillingness to address fundamental challenges made the pandemic much worse than it had to be for First Nations across Canada.

Melissa Mbarki is the Policy Analyst and Outreach Coordinator at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. She is from the Muskowekwan First Nation and is a consultant and operations analyst for natural resource projects in Western Canada.