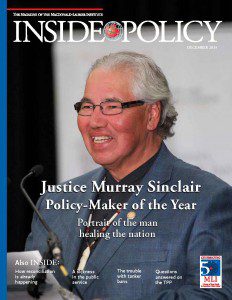

In a moving interview, Justice Murray Sinclair tells Inside Policy’s Robin Sears why chairing the Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission was something he ‘was meant to do’, and how he hopes it will change Canada for the better.

In a moving interview, Justice Murray Sinclair tells Inside Policy’s Robin Sears why chairing the Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission was something he ‘was meant to do’, and how he hopes it will change Canada for the better.

This article appears in the December 2015 edition of the magazine.

By Robin V. Sears, Dec. 15, 2015

At the end of a long emotionally candid conversation, Justice Murray Sinclair asks reflectively, “And you know what it will take for reconciliation?”

It’s not a rhetorical question and he awaits an answer.

“Well, it’s acceptance, it’s forgiveness I guess … it’s …” and I stumble into silence, knowing I have not passed his test.

“No, that comes later. First it is acknowledgement that our spirituality – Aboriginal spirituality – is the equal of yours. Without that it’s just a campaign for slow assimilation.” It’s a stark and surprising answer from this most gentle but powerful of voices.

Raised as a Catholic, Sinclair almost trained for the priesthood. He describes himself as a deeply spiritual person. But as his definition of reconciliation makes clear, his spirituality refuses to place one faith above another.

Murray Sinclair is not only an esteemed judge – Manitoba’s first Indigenous senior justice – and teacher, he is a student of those like him who have devoted years to trying to resolve the meaning behind, and to begin the healing from, atrocity.

He quickly sketches the connection between the denigration by residential schools and Canadian society of the values and spiritual beliefs of Aboriginal peoples and the neglect, abuse and perhaps even criminal negligence leading to hundreds, maybe thousands, of deaths of children. Those boys and girls of First Nation, Métis and Inuit families were seized by the state and imprisoned in residential schools designed to assimilate them into white society.

Murray Sinclair is not only an esteemed judge – Manitoba’s first Indigenous senior justice – and teacher, he is a student of those like him who have devoted years to trying to resolve the meaning behind, and to begin the healing from, atrocity. He has read extensively about Gandhi, Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Martin Luther King and believes in their teachings of confrontation without violence. He believes in the importance of truth and respectful reconciliation, and he acknowledges the importance of working for reconciliation with an understanding of the role of forgiveness to personal healing. He recalls his conversation with Freddy Mutanguha, a survivor of the Rwanda genocide who is now Executive Director of the Kigali Memorial Centre of Rwanda, an archive and reconciliation centre devoted to the genocide. Mutanguha described his fight to get back to a functioning life, his struggle to find the path to forgiveness of his neighbours, who had hacked his family and friends to death.

Murray Sinclair is not only an esteemed judge – Manitoba’s first Indigenous senior justice – and teacher, he is a student of those like him who have devoted years to trying to resolve the meaning behind, and to begin the healing from, atrocity. He has read extensively about Gandhi, Mandela, Desmond Tutu and Martin Luther King and believes in their teachings of confrontation without violence. He believes in the importance of truth and respectful reconciliation, and he acknowledges the importance of working for reconciliation with an understanding of the role of forgiveness to personal healing. He recalls his conversation with Freddy Mutanguha, a survivor of the Rwanda genocide who is now Executive Director of the Kigali Memorial Centre of Rwanda, an archive and reconciliation centre devoted to the genocide. Mutanguha described his fight to get back to a functioning life, his struggle to find the path to forgiveness of his neighbours, who had hacked his family and friends to death.

Sinclair pauses, recalling the emotion of the moment. He talked about how Mutanguha had to go through a process of forgiveness in order to be able to do the work he does for reconciliation in his country and then said, “He told me that forgiving was not easy for him but he was able to do it, but that each morning, when he gets up, he has to begin the process all over again. Each day he must fight to forgive his neighbours and the thousands of other perpetrators all over again.”

Sinclair doesn’t say that this is his challenge. But you can tell that after the years and years of survivor testimony, the almost endless telling of the most horrific abuse of small children, forgiveness has been and still is a personal struggle for this impressive leader.

Earlier he discussed the gap between the silent Canadian perpetrators and their victims. Since its launch in the 1880s a staggering 150,000 aboriginal children had been forced into the residential school system. Of the estimated 79,700 survivors of the 139 residential schools alive in 2006, almost half, or 37,000, reported having suffered serious physical or sexual abuse.

The horror for generations of Aboriginal children was not limited to residential schools.

“Now,” he adds, “Consider this. We have no way of knowing how many victims each of the perpetrators typically abused. For the purposes of rough calculation, let’s say it was roughly a dozen each. That means there were around 3,000 abusers of those children, many of whom would have been alive in 2006 as well. Some of them are no doubt still alive.”

“Do you know how many have come forward voluntarily, to apologize, to seek forgiveness, to seek reconciliation with their victims? … Precisely none. Zero.”

The horror of that calculation sits heavily in the silence between us. I mutter overwhelmed, “… in Canada.”

Sinclair adds that the horror for generations of Aboriginal children was not limited to residential schools. Many reports of the systemic racism and abuse inflicted on Aboriginal students in the public school system in small towns across Canada, have also emerged in the TRC’s work. Indigenous students in public schools were also shamed and dehumanized by a system that taught generations of children that Aboriginal people were heathens, savages, pagans, uncivilized, weak and inferior. It also taught that European societies were smarter, superior, more just and more civilized. This has created a great divide in society he points out, and why reconciliation is not just an Aboriginal problem, it’s a Canadian one.

Sinclair adds that the horror for generations of Aboriginal children was not limited to residential schools. Many reports of the systemic racism and abuse inflicted on Aboriginal students in the public school system in small towns across Canada, have also emerged in the TRC’s work. Indigenous students in public schools were also shamed and dehumanized by a system that taught generations of children that Aboriginal people were heathens, savages, pagans, uncivilized, weak and inferior. It also taught that European societies were smarter, superior, more just and more civilized. This has created a great divide in society he points out, and why reconciliation is not just an Aboriginal problem, it’s a Canadian one.

In short, stark phrases he sketches the cascading impacts of the destruction on generations of young Aboriginal lives and on the entire Aboriginal community in Canada. “It’s not an exaggeration to say that there are few Aboriginal families that do not still bear the scars of this system.” Institutionalization meant that there were no parents to teach parenting skills. Demeaning abuse for years led to deeply self-destructive later lives. Abuse begat abuse. And on and on.

Murray Sinclair arrived at the momentous responsibility of attempting to find a path forward from Canada’s worst atrocity unwillingly and with deep hesitation. He turned down the task when first approached in 2007. As he recalled, he had already been through an inquiry in Manitoba into the deaths of children in the province’s health care system. Emotionally exhausted from that experience, he withdrew from consideration of heading the TRC, knowing how emotionally grueling it would be.

However, the first attempt at starting the Truth and Reconciliation Commission collapsed in acrimony the following year, with a pained and angry Justice Harry Laforme’s public dissection of the reasons for the commission’s failure. Sinclair knew that it would be hard for him to refuse a second time. He knew how crushed the survivors and their families were by the TRC collapse.

Its achievement, Sinclair is determined, will be not to meet the same fate as the similarly vast Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, that may have informed some Canadians, but did little to inform changes in public policy

When the call to head the Commission once again came in the spring of 2009, he consulted his family, his children, his friends. They helped him understand that it was something he “was meant to do.” He could not say no, but as a seasoned judicial and political warrior he knew he could exact a price for his yes.

He won independence, financial control, and the final say in the choice of fellow commissioners and staff. The bevy of government employees who had been part of the first fiasco, on secondment from what was then still called the department of ‘Indian Affairs,’ were sent back to their employer, and the Commission headquarters were moved from Ottawa to Winnipeg.

Sinclair does not offer anything further about the reasons for that complete overhaul, but his message to government was clear – this is my task, and I will lead it with those I trust and choose to assist us. He approved the choice of Marie Wilson, a former journalist, and Chief Willie Littlechild, a former MP and Alberta chief as the other two commissioners. They made an impressive team.

Born near Selkirk, Manitoba, in 1951, Murray Sinclair was raised by his grandparents and extended family, following the death of his mother when he was an infant. He credits his grandmother Catherine for the sense of duty and spirituality she imbued. She was clearly a powerful and positive influence, motivating him to become valedictorian and athlete of the year in high school. After working as a young assistant to then Manitoba Attorney General Howard Pawley, he worked his way through university, earning his law degree from the University of Manitoba. He established a reputation as a civil and criminal advocate and for his knowledge of human rights, as well as Treaty and Aboriginal rights, through his work as legal counsel for the Manitoba Human Rights Commission and legal counsel for the Manitoba Métis Federation and the Chiefs of Manitoba.

Appointed as Associate Chief Judge of the Provincial Court of Manitoba in 1988, Justice Sinclair became Manitoba’s first Aboriginal judge. In neat serendipity, in one of his first boss’ final acts as premier, Howard Pawley named him as co-commissioner of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. It was a powerful introduction to his subsequent work at the TRC, coming face-to-face with the Aboriginal victims of a flawed system of justice. In addition to his work as a respected jurist, he also had to examine the failings of the healthcare system as the head of an inquiry into the deaths of 12 infants at a Winnipeg hospital. The reports he authored for both inquiries have influenced changes in the justice and health care systems across the country.

Appointed as Associate Chief Judge of the Provincial Court of Manitoba in 1988, Justice Sinclair became Manitoba’s first Aboriginal judge. In neat serendipity, in one of his first boss’ final acts as premier, Howard Pawley named him as co-commissioner of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. It was a powerful introduction to his subsequent work at the TRC, coming face-to-face with the Aboriginal victims of a flawed system of justice. In addition to his work as a respected jurist, he also had to examine the failings of the healthcare system as the head of an inquiry into the deaths of 12 infants at a Winnipeg hospital. The reports he authored for both inquiries have influenced changes in the justice and health care systems across the country.

When Minister Chuck Strahl asked him to reconsider chairing the TRC, Justice Sinclair knew it would be a long and tough assignment. He did not expect that it would consume six and half years of his life … so far. But an even bigger surprise awaited him nearly half way through his long journey.

He had been through years of grueling testimony by that point and he wanted some quiet time with family. He visited a favorite uncle who stunned him with the news of his own link to the horrors of the residential schools. His uncle told him what he had never been told: that his own father had been a victim of abuse in residential schools.

As Sinclair described it to Postmedia’s Mark Kennedy, suddenly “everything clicked into place for me to explain why my father was the way he was.” A combat veteran, Henry Sinclair had died nearly two decades earlier after a life of struggle with alcohol, violence, loneliness, homelessness, and despair. While the birth of his grandchildren had brought his father to the point of redemption, sobriety and a sense of peace in his later years, he always presented to Justice Sinclair as a guarded man with secret pain that prevented him from sharing love or laughter with his children, but which he could freely share with his grandchildren.

“I had challenged him to change when my son – his first grandchild – was born,” Sinclair recalled, “and he did. I expressed to him my deepest thanks for having done so, as he lay in hospital waiting for his end to come, and he was grateful to hear that. I came to hear of similar events in the lives of many survivors, and I had been witness to just such a transformation with my father, without understanding its implications until that day with my uncle. It caused me to see the importance of intergenerational survivors forgiving their parents if they could, while they were still alive – the single most important act of reconciliation most survivors need and want.”

The work of the Commission covered a vast terrain, both geographically and in the sheer volume of witness hearings and the thousands of Canadians who participated in the TRC’s national events. The Commissioners traveled to dozens of communities from the far North to virtually every Canadian town and city – and heard from almost 7,000 of the survivors themselves.

Its recommendations cover the entire sweep of Canadian history, constitutional and civil law, and will require – with even partial implementation – enormous changes in the relationship not only between Canadians and Canada’s Indigenous Peoples, but changes in the role of governments, the private sector and civil society at many levels.

Its achievement, Sinclair is determined, will be not to meet the same fate as the similarly vast Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, that may have informed some Canadians, but did little to inform changes in public policy. Sinclair wants the work of the TRC to go on under the leadership of a National Council for Reconciliation, but points out that every Canadian has a role to play. At the Duff Roblin Award dinner in which he was recognized for leadership in the field of education, Justice Sinclair observed: “Reconciliation begins for each of us with one very simple concept reflected in the events at first contact and in the Treaties: I want to be your friend, and I want you to be mine. When you need me, I’ll have your back, and when I need you, you’ll have mine. We are going to be in this country together a long time and our ancestors knew that, but my ancestors believed, as do I, that we can walk together on this road, friends forever, without surrendering our sense of self, and yours did too.”

The next major investigation of these sad chapters of Canadian history is about to be launched with the creation of an Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls. Its challenges will be even greater than those faced by Sinclair and his colleagues. They will face active opposition from some institutions and groups of Canadians. The possibility of a bitter finger-pointing prosecutorial process is quite real, in the fears of some close to the leadership of First Nations communities. The new commissioners would be wise to spend some long hours with Justice Sinclair learning from his experience.

Asked to what he attributed the TRC’s success, he says bluntly, “I knew where we needed to go. I wrote in detail what I wanted to achieve, and how I thought we could get there, before we even began.” He adjusted the goals and the journey a little, but basically stuck to his roadmap even as the finish line appeared to keep receding in front of him.

If he is successful in transforming the healing process he began into real change, he will have changed Canada – and probably have set new standards to be copied in the rest of the world on both the reset of relations with Indigenous peoples in many societies and on authentic reconciliation work. The massive final report will be presented to the government in mid-December. (Those interested in the source testimonies will find hundreds of hours of material at the commission’s website, trc.ca.)

If he is successful in transforming the healing process he began into real change, he will have changed Canada – and probably have set new standards to be copied in the rest of the world on both the reset of relations with Indigenous peoples in many societies and on authentic reconciliation work. The massive final report will be presented to the government in mid-December. (Those interested in the source testimonies will find hundreds of hours of material at the commission’s website, trc.ca.)

Sinclair and the Commissioners are clearly the beneficiaries of the new government; one with a prime minister and minister publicly committed to carrying out their recommendations. Carolyn Bennett, the new minister responsible for relations with Canada’s indigenous peoples commented on Sinclair and the reconciliation process and offers him high praise, saying,

“Canada owes an enormous debt of gratitude to Murray Sinclair. He has taken great care to show Canada the best path toward reconciliation. I am honoured to take up Justice Sinclair’s challenge of involving all Canadians in this unfinished work of Confederation.”

The Commission has produced thousands of pages of documentation and Calls to Action, many of which are painful judgments on the role of the Government of Canada. It calls for complex changes, not the least of which is a change of attitude. Sinclair acknowledges that many changes call for an expenditure of funds, but challenges all critics to consider what “the cost of doing nothing” is going to be. “We are spending billions of dollars per year in maintaining a broken relationship and funding a system of governance that has proven over many generations that it is never going to fix things. It’s time to fix this relationship and the way we are doing business, properly.”

It is hard to imagine any previous prime minister making such a sweeping commitment to a report like this. Hard to recall, either, such a ringing endorsement of a commissioner offering such tough medicine from any previous minister.

Many times past, Canadians have failed at completing the work of genuine reconciliation.

It will be Bennett’s challenge to unite the entire Cabinet and government behind their commitment to make the process real. A tough former family doctor used to marshaling recalcitrant patients, Bennett has devoted years to work in the First Nations. She will not be easily deterred by the foot-dragging of a department famous for its ability to slow-walk ministers into frustrated paralysis.

As Sinclair finished this chapter of the Commission’s work, he is clearly proud of the achievement, prouder still that both his son and daughters are now employed in reconciliation work in separate projects.

Decompressing from the years of almost daily emotional stress is something he is clearly relishing. He chuckles at his satisfaction in just having spent several hours raking his yard and cleaning his garage in preparation for winter. Perhaps he will write, he says, maybe teach, but not right away.

Given his tremendous success at a task that looked hopeless only a few years ago, one suspects that his phone may ring again. The path to reconciliation that he and his fellow commissioners have blazed for Canadians will not be smooth, short or free of future roadblocks. Many times past, Canadians have failed at completing the work of genuine reconciliation.

Canada is indeed fortunate to have had such an inspirational leader come forward at a moment when we face a potentially fateful fork in the road between another Oka – the very real prospect of violent confrontation – and Justice Sinclair’s path.

We may again need his unique blend of wisdom and gentle humour, his quiet, courteous, but relentless determination to set us firmly down the right path one more time.

Contributing writer Robin V. Sears, a former national director of the NDP, is a principal of the Earnscliffe Strategy Group.