This article initially appeared in Discourse Magazine and is being republished with permission. The full original article can be read here.

By Brian Lee Crowley, October 15, 2021

Patriotism, according to Samuel Johnson, is the last refuge of a scoundrel. If the views of young people in both Canada and America are anything to go by, they largely agree with Johnson.

Across North America today, the young are far more conditional in their enthusiasm for their countries than are their elders. This is borne out in polling as well as the largely youthful support for movements such as taking a knee at sporting events, Black Lives Matter, Antifa, the One Percenters, the call to cancel Canada Day and more.

If this is just a new manifestation of the old phenomenon of idealistic youth versus worldly-wise experience, it is perhaps nothing to worry about. If, by contrast, it portends a long-term shift in people’s love for Canada and the U.S., I think that would be not just a pity, but a loss to both countries and the world.

Reckoning With History

In a way, I am not surprised that young people view both nations with some suspicion. Much of what they have been taught is that our past is nothing but a repository for all that is retrograde and shameful. They believe it is filled with racism, sexism, homophobia, colonialism, militarism, genocide and environmental destruction.

But looking solely at our past errors—and we have made our share—is not the right standard by which to measure the U.S. and Canada and our great achievements. In all human history, only a handful of societies have figured out, slowly and painfully, the institutions and behaviors that allow us to corral the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: pestilence, war, famine and death.

The U.S. and Canada are at the forefront of those societies, and it is thanks to our history of struggle against the worst human afflictions that we now enjoy the conditions where our young people can look back in horror at how things used to be. It is the progress made possible by the economic, social and, yes, moral advances of our forebears.

We cannot change the past, but our determination to ensure that past mistakes will not recur does not require us to despise our past. The true measure of a man or a woman or a country is not mistakes—for who among us has never made a mistake?—but how those mistakes are answered, by taking responsibility, making amends and making every effort to ensure they don’t happen again. On this measure, Canada and the U.S. have little of which to be ashamed and much of which to be proud.

The youthful progressives and their leaders among us reject this account. Their argument is roughly this: You say that our societies are inextricably bound up with values of freedom and equal treatment under the law, yet look at how we have so signally and consistently failed to live up to those ideals, which are far more rhetorical than real. Look at the treatment over the years of Blacks, women, Indigenous people, other racial and sexual minorities, immigrants, would-be immigrants and others. Only a vicious society of which we should be ashamed could have acted in this way.

But I look at our history, recognize those undoubted abuses and failures, and draw exactly the opposite conclusion. The institutions we so value, which are at the heart of liberal-democratic societies like ours, are themselves the result of an evolutionary process by which the dross of self-interest and prejudice is slowly purged. As this occurs, their reach is progressively expanded to embrace more and more of society’s members, as in the extension of the right to marry to those previously excluded, such as gays and lesbians.

Institutions and Interest Groups

Progressives’ hostility to the traditional, and particularly to traditional institutions, arises from a misunderstanding of the origins of institutions and practices, on the one hand, and the relationship between history and liberal-democratic ideals on the other.

It may be that many of our common institutions find their origins in the interests of particular groups. Private property, for example, may have its origins in the desire of those who had wealth to protect themselves from those who did not. (I do not think that this is the case, but let’s accept it for the sake of the argument.) But once in place, such institutions can be and are turned to the benefit of those who had no hand in their creation. Indeed, one might argue, for example, that what Indigenous groups in Canada are now claiming is a particularly robust form of property right to Indigenous lands that is intended to protect them from interference by the non-Indigenous.

Something similar was at work in the taming of political power and the evolution of representation. Following the Norman invasion of Anglo-Saxon England, the monarch ruled with largely untrammeled power, although that power was somewhat diluted by the need to conciliate the nobles on whose land, soldiers and wealth the king depended. When the king became too overbearing, demanding and dismissive of the role and authority of the barons, they allied against him and at Runnymede forced him to commit himself in writing to respect their traditional power and rights. The result was the Magna Carta. But why do we hark back to the Great Charter when in fact it was merely a deal worked out among the powerful few, one that conferred little benefit on the many?

The answer is because it began an evolutionary process by which political power had to extend the range of those whose interests were to be considered in the exercise of that power, and whose rights had to be protected in consequence. The Magna Carta unleashed a process by which more and more members of the population were included in the circle of those who enjoyed rights.

That process moved through stages that included the toleration of religious dissent and recognition of rights of conscience and belief, enjoyment of private property and of freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, the Reform Acts of the 19th century, the enfranchisement of women and various minorities, the abolition of slavery, the elimination of property-ownership voting requirements and many other reforms. Each of these changes was made to eliminate defined abuses, and their adopters’ intentions did not necessarily include universal suffrage or universal enjoyment of rights, however much that might have been in the minds of those who agitated for reform.

Universalizing these rights was an incremental process whose full outcome few foresaw. The point, however, was that those who enjoyed power needed to share what had hitherto been their privileges with ever-greater swathes of the population, turning privileges (that is, “private laws”) into public benefits. As the protected sphere belonging by right to individuals was gradually expanded, it became clear that the unintended benefit was the development of institutions that protected and buttressed human freedom, flourishing and prosperity. But it was a long and slow process to purge from these institutions the dross of partiality and privilege.

The Redefinition of the Public

A lovely example of this universalizing process at work is the establishment of British public schools, such as Eton and Harrow. In North America these would be called private schools, and people here regard the fact that they are known as public schools as one of these inexplicable examples of perverse British eccentricity, like enjoying warm beer and driving on the left.

But the term “public school” is a holdover from another age when the term was perfectly apt. Before universal suffrage, “the public” referred to those people entitled to participate in the public life of the country, those eligible to vote in and stand for elections to the Commons or to sit in the Lords. Those were the people who got to decide the questions of the common good. They were both public people and private ones, in the sense of having lives outside the public sphere. Public schools were the place those who would have public responsibilities, who would be the public, were educated.

Everyone else, however, had only a private life; there was no officially public aspect to their persona. They were the object of laws and public administration, never the subject. They were acted upon by government but never actors, except in the sense of occasionally using non-official protest as a means of calling attention to their complaints. The struggle over the franchise was about who would be counted among “the public.” The answer has so resoundingly been “everyone” that today the idea of a “public school” in the traditional British sense is literally incomprehensible to Americans and Canadians, even though the franchise was heavily restricted in both those countries long after their foundings.

Now everyone has a public and a private persona. We think of public schools as what they have become: the place where a universal education occurs for a universal public. “Private schools” are for those who opt out of the common regime. The lesson to take from this is that a long historical process transformed the notion of “public” from a privilege enjoyed by the few to a universal right enjoyed by everyone.

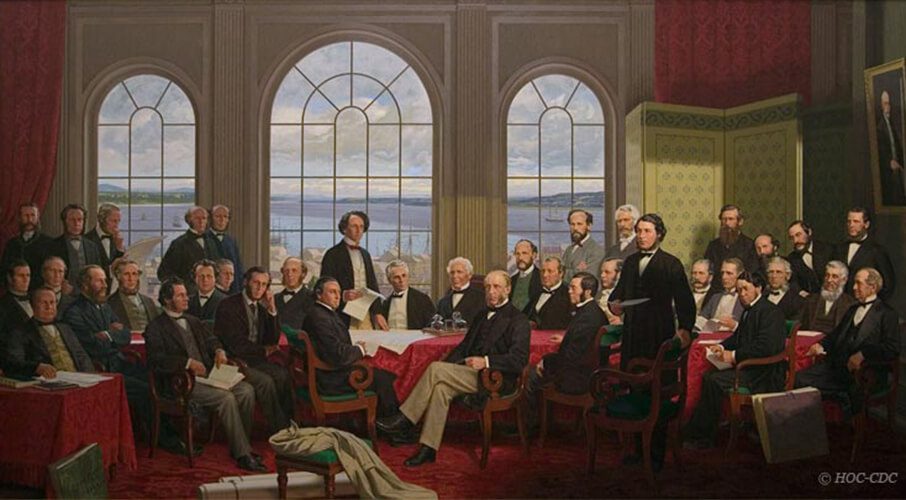

When the British political order, culture and institutions crossed the Atlantic, they eventually inspired both America’s founding and Canada’s confederation. In both instances the founders were moved by the same vision of human freedom and flourishing implicit in the British political heritage; remember, the American revolutionaries argued they were merely vindicating the traditional rights of Englishmen. But being imperfect human beings, their prejudices prevented them from understanding the potential of every human being to benefit from the rights and freedoms they so rightly extolled.

The subsequent history of both countries has been shaped in part by the struggle to extend those rights and freedoms to all: women, oppressed minorities, Indigenous people and others. Americans fought a civil war not to repudiate their founding principles, but to extend their benefits to those wrongly excluded. Slavery was an obvious derogation from the universalist pretensions of the American project. As in the case of British “public” schools, the operating assumption of the day was that slaves, women and those with no property were not members of the community of the public that made decisions about common life.

Slaves were also denied a private life. They had no private spaces, no property, no right to decide whom to marry or have sex with, what job to hold or for whom to work. To us those exclusions are anomalous, but not to most people of the time. The abolition of slavery (the recognition of the essential humanity of enslaved people) and the extension of the franchise were part of a long working-out of the conflict between the universalist ideas underlying the foundings of the U.S. and Canada and the exceptions that prejudice and partiality carved out from those principles at the time.

Expanding, Not Rejecting, Founding Principles

As we abolished slavery, expanded the franchise, recognized the personhood of women, enlarged the circle of immigration, aimed to combat racism, enhanced minority rights and, most recently in Canada, sought reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, we did so using language, concepts and aspirations that informed the American founding and Canadian confederation, and the British political heritage from which both drew inspiration.

That is why the argument of those previously excluded had such moral force: They appealed to concepts such as rights and equality that have long been part of our heritage but were imperfectly understood and applied. A balanced view of our past acknowledges the imperfections of what was done but also the soundness of the universalist vision that inspired our past and the efforts made to fix our errors. We cannot change the past, but we do not have to despise our past to say that past mistakes shall not be tolerated on our watch.

Our most successful social reforms have been those that brought the wrongly excluded fully into the circle of benefits of membership in a liberal-democratic society. The progressives see the exclusions of the past as an irredeemable indictment of liberal individualism, a creation tainted by the bigotry, racism and sexism of the founders. They therefore call for its overthrow, but the battle to remove the exclusions is itself a vindication of the rights to which the wrongly excluded have so eloquently appealed.

Our past, while helping to highlight areas where we can and must do better, is no reason to hang our head in shame. On the contrary, it is reason for us to thank our lucky stars that those who went before us built the foundation as solidly as they did, giving us the concepts and tools necessary to extend over time the benefits of liberal democracy to all who live here and those yet to come.

Brian Lee Crowley is the managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. This article is an edited extract from his recent book, “Gardeners vs. Designers: Understanding the Great Fault Line in Canadian Politics” (Sutherland House, Toronto, 2020).