This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Tim Sargent, July 22, 2024

DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

Few policy goals command broader political support than increasing the well-being of children. It seems self-evident that any society that wants to secure its long-term future needs to be investing in the citizens, workers, and taxpayers of tomorrow. Both the Conservative government of Stephen Harper—with its Universal Child Care Benefit—and the current Trudeau government—with its Canada Child Benefit—made income support for families with children a key policy priority.

However, the policy debate about how best to improve outcomes for children—both in Canada and in countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom—has had something of a blind spot in recent years. Despite the enormous changes in rates of marriage and divorce over the last half-century, there has been very little discussion of the role that family structure has to play in affecting children’s well-being. As we shall see, fewer than six out of 10 Canadian children live with their original parents, and many of those will see their families break up before they reach adulthood.

And yet, there seems to be a fear that any discussion of the relative merits of different family structures is “hurtful to the families being talked about and hurtful to our culture,” in the words of the Vanier Institute for the Family, a Canadian think tank that focuses on family issues. As well-known economist Tyler Cowen said in a 2022 interview with The Hub, “For many people, [family structure] is a subject you’re not even really allowed to bring up.”

But perhaps not anymore.

Two-parent families in the spotlight

The last year has seen two American authors put their heads above the parapet. The first was Melissa Kearney, an economics professor at the University of Maryland, a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. Her September 2023 book The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind is a data-driven look at how divergences in family structure in the U.S. have exacerbated high rates of income inequality. In a podcast discussion with The Hub in March she drew attention to the situation in the U.S., where:

the most highly educated, high-income segments of society are still getting married at high rates, raising their kids in two-parent families at high rates. Others in society who are struggling economically, their economic struggles are made worse by the fact that now they’re more likely to have just one adult, one parent in the household. Their kids fall further behind and that cements the inequality and perpetuates it across generations.

While the Washington Post, perhaps not surprisingly, dismissed Kearney’s book as “tiresome,” the reaction of the other house journal of liberal America was quite different: the New York Times published a guest essay by Kearney outlining the ideas in her book, and columnist Nicholas Kristof gave her work a sympathetic review in a column entitled “The One Privilege Liberals Ignore.”

In March of this year, Brad Wilcox, a sociologist from the University of Virginia, published Get Married: Why Americans Must Defy the Elites, Forge Strong Families, and Save Civilization, a book with a similarly clear message about the benefits of marriage for children. In another Hub podcast discussion, he argued that:

poor kids in communities across America are more likely to rise from poverty into affluence, that classic rags to riches story, when they’re growing up in communities where there are lots of two-parent families. A poor kid growing up in Salt Lake City is much more likely to become affluent as an adult compared to a poor kid growing up in Atlanta. That’s in large part because there are many more two-parent families in Salt Lake than there are in Atlanta.

Both these books build on extensive evidence from the U.S. and elsewhere that children who grow up in intact families—i.e. with their original parents (biological or adoptive)—have higher educational attainment, are less likely to engage in risky or delinquent behaviour, and have lower incarceration rates and teen pregnancy rates. Nor is the benefit of being in an intact family simply a result of the much greater financial resources relative to single-parent families: boys especially can often go astray without a father present in the home to be an appropriate role model. (This point is made eloquently in the new book Of Boys and Men, written by Richard Reeves, a former adviser to the British Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg and now senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.)

Children also do less well in stepfamilies: children are much more likely to be abused or neglected in a stepfamily than they are in an intact family. Furthermore, at least in the U.S. data, families where the parents are married also seem to produce better outcomes for children than families where the parents are in a common-law relationship (i.e. cohabiting), partly because those relationships are less stable, and this instability has a negative effect on children.

With the idea that marriage might produce better outcomes for children than common-law relationships or single parenthood now the focus of serious debate in the U.S., it is perhaps a good moment to take a look at the state of two-parent families in Canada, which is what we plan to do in the rest of this article.

Trends in two-parent families over time

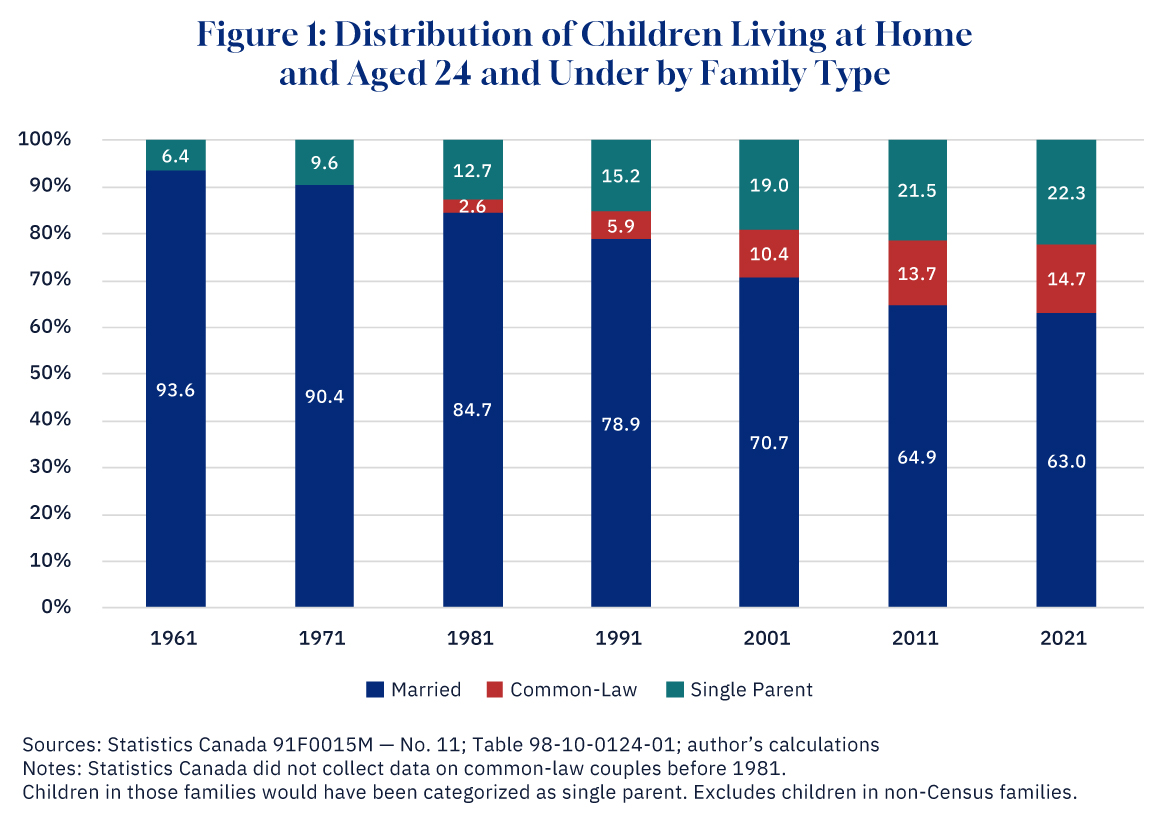

Figure 1 shows the proportion of Canadian children living in one of three family types: married; common law (sometimes called co-habiting); and single parent. The share of children in married-couple families has declined steadily over time, from 93.6 percent in 1961 to 63 percent today. Of that 30.6 percentage point drop in the share of children in married-couple families, about half (15.9 percentage points) is accounted for by a rise in the share of single-parent families, with the other half (14.7) accounted for by a rise in the share of children in common-law couple families.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Interestingly, the biggest decline in the proportion of children in married-couple families took place not in the 1960s or 1970s, the decades that saw the legalisation of divorce and the decriminalisation of homosexual activity, but in the 1990s, as the children of the baby boomers came of age. Since 2011 the pace of decline has slowed although not halted, with the proportion of children in married couple families dropping 1.9 percentage points between 2011 and 2021, compared to a 5.8 percentage point drop between 2001 and 2011.

Intact families versus stepfamilies

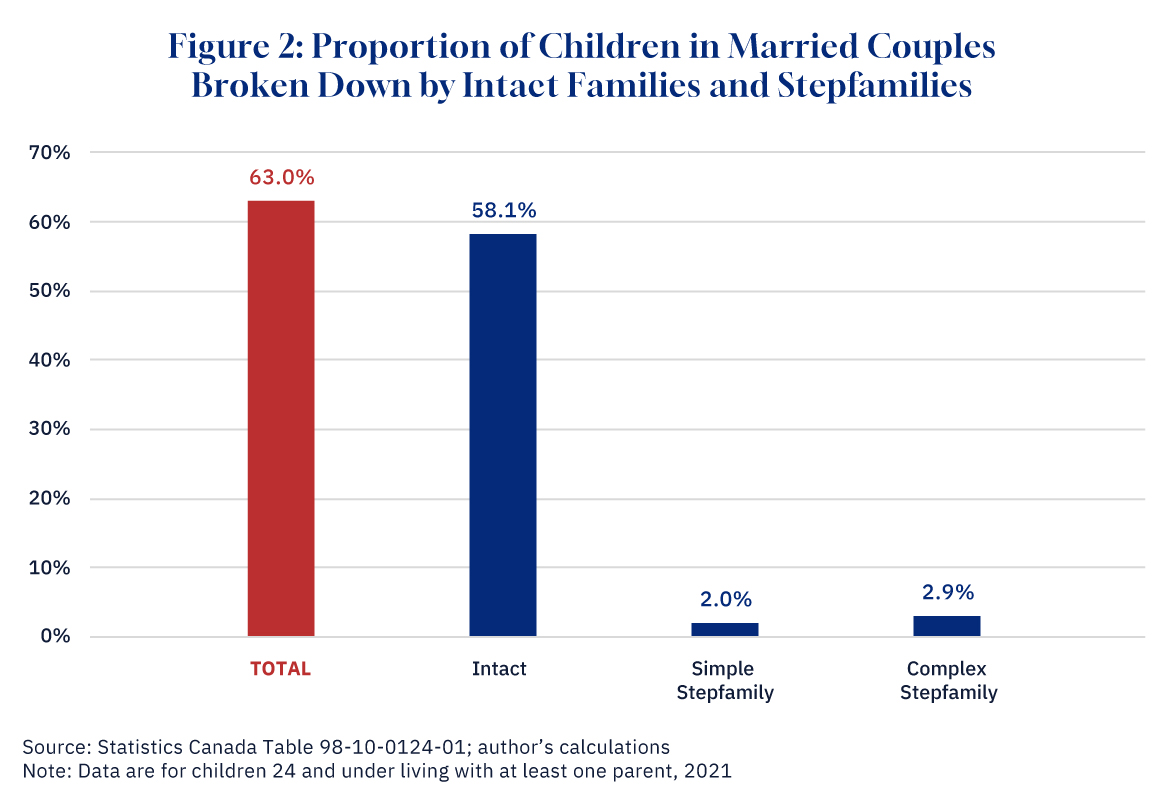

It’s important to note that not all children in married-couple families live with their original parents (either birth parents or adoptive parents). Many live in stepfamilies, due to their parents being divorced and they now live with one of their original parents and this parent’s new spouse. Statistics Canada breaks down stepfamilies into two types: simple stepfamilies, where all the children living at home are the original children of only one of the parents; and complex stepfamilies, where there are children who have different birth parents.

This distinction matters significantly for outcomes, because, as noted above there is significant evidence that children do not do as well, on average, in stepfamilies as they do in intact families.

Figure 2 below shows how the children in married-couple families are distributed between intact families, simple stepfamilies, and complex stepfamilies. Of Canadian families, 58.1 percent of children live in intact families, with 2 percent in simple stepfamilies and 2.9 percent in complex stepfamilies. Thus, a bit less than a tenth of children in married-couple families live in stepfamilies.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

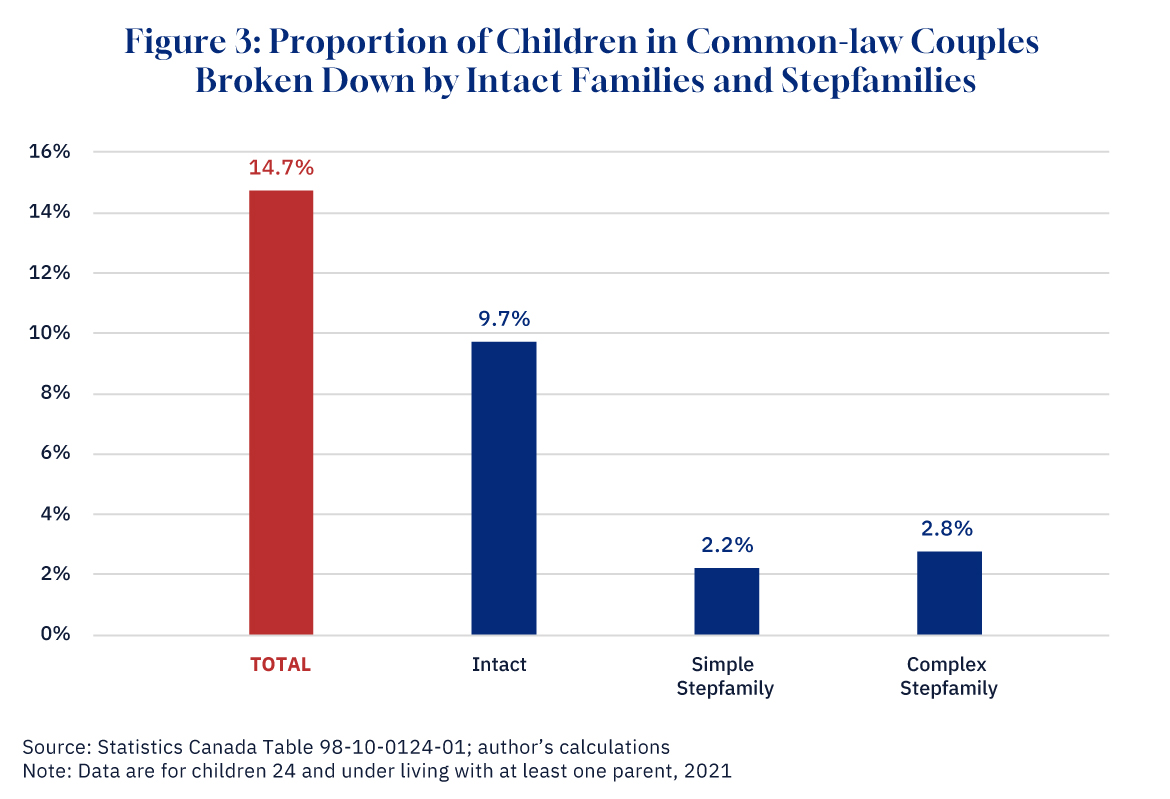

Figure 3 shows the same breakdown for common-law couples, where 9.7 percent of children in Canadian families live in intact families, whereas 2.2 percent live in simple stepfamilies and 2.8 percent in complex stepfamilies. This means that about a third of children in common-law couple families live in stepfamilies.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The much higher prevalence of stepfamilies in common-law relationships likely reflects the reluctance of people who have lived through the breakup of a previous relationship to remarry, as well as the greater instability of these relationships.

Adding together the proportion of children in intact married-couple families and intact common-law couple families implies that 67.8 percent of Canadian children live in an intact family. However, that number is simply a snapshot in time: many children currently in intact families will see those families break up over time, so the proportion of children who reach adulthood still in an intact family is likely to be significantly less.

Breakdown by province and urban-rural

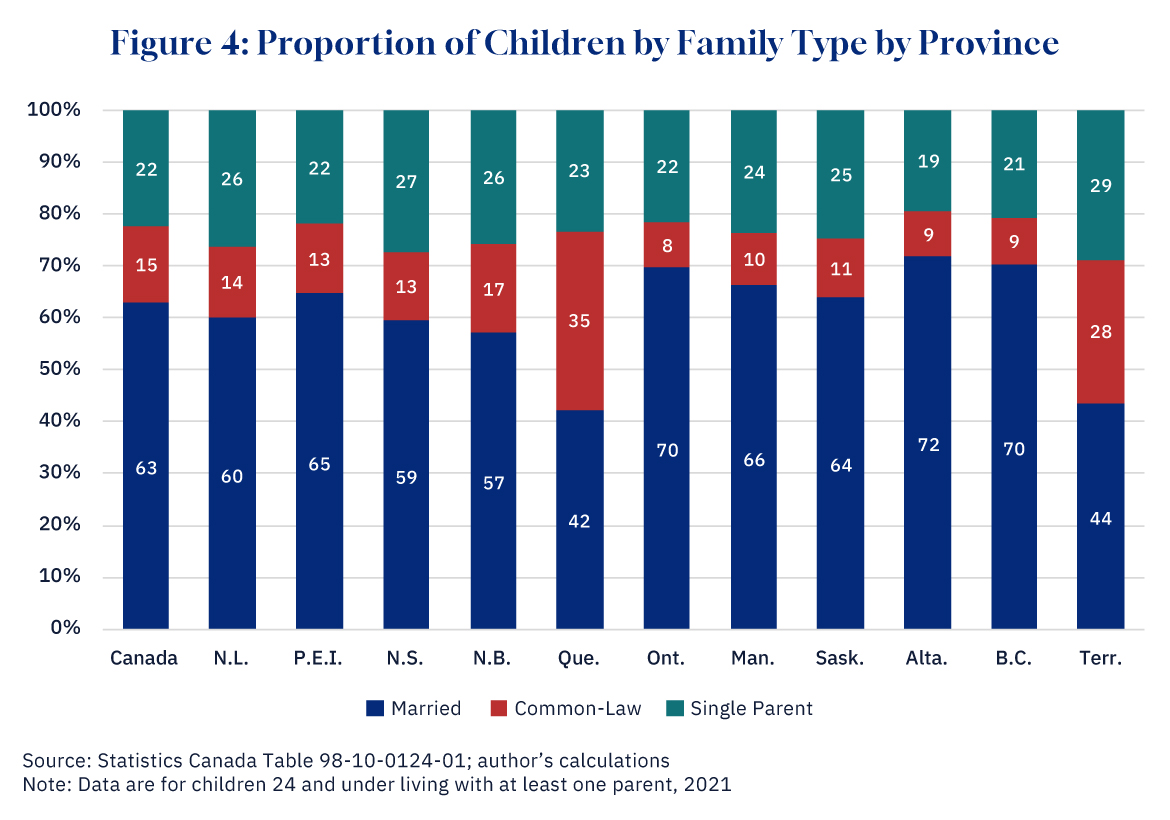

How do the proportions of children in different types of families vary across the country? Figure 4 answers this question for the provinces and territories. Quebec has the lowest proportion of children in married-couple families, with only 42 percent in this kind of family (compared to 63 percent for Canada as a whole) and 35 percent in common-law families (compared to 15 percent for Canada). This difference reflects the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, when Quebec went from being one of the most religious parts of Canada to one of the most secular. Interestingly though, the proportion of children in single-parent families is only 23 percent, just slightly above the Canadian average of 22 percent, and so the greater incidence of common-law couples doesn’t seem to have led to many more children in single-parent families.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Looking at the rest of Canada, the Territories also have a high incidence of children in common law families: in this case, however, they also have a higher proportion of children in single-parent families—29 percent, the highest in Canada.

Alberta has the highest proportion of children in intact families, with 72 percent of children in this kind of family, closely followed by B.C. and Ontario (both at 70 percent). Manitoba (66 percent) and Saskatchewan (64 percent) have somewhat lower proportions of children in intact families.

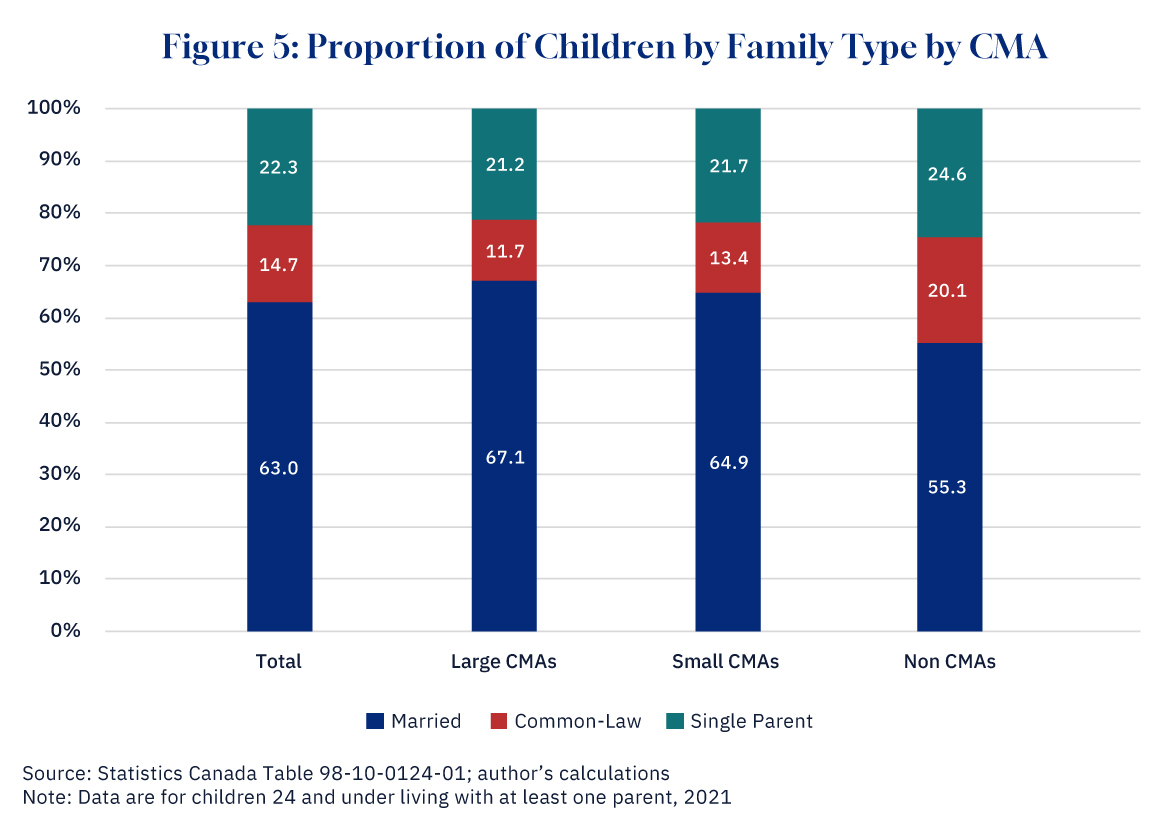

Interestingly, the Atlantic provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick have significantly lower proportions of children in intact families (60, 59, and 57 percent respectively), with correspondingly higher shares of children in common-law and single families. This difference with Ontario and the West may reflect the rural nature of these three Atlantic provinces. Figure 5 shows the breakdown for large Census Metropolitan Areas (CMAs) (Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver), small CMAs (other towns and cities with over 100,000 people), and non-CMAs (small towns and rural areas).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

It’s readily apparent that there are fewer intact families in more rural areas: in the three largest CMAs, 67.1 percent of children live in intact families, compared to 64.9 percent of children in smaller CMAs, and only 55.3 percent in non-CMAs.

Family size

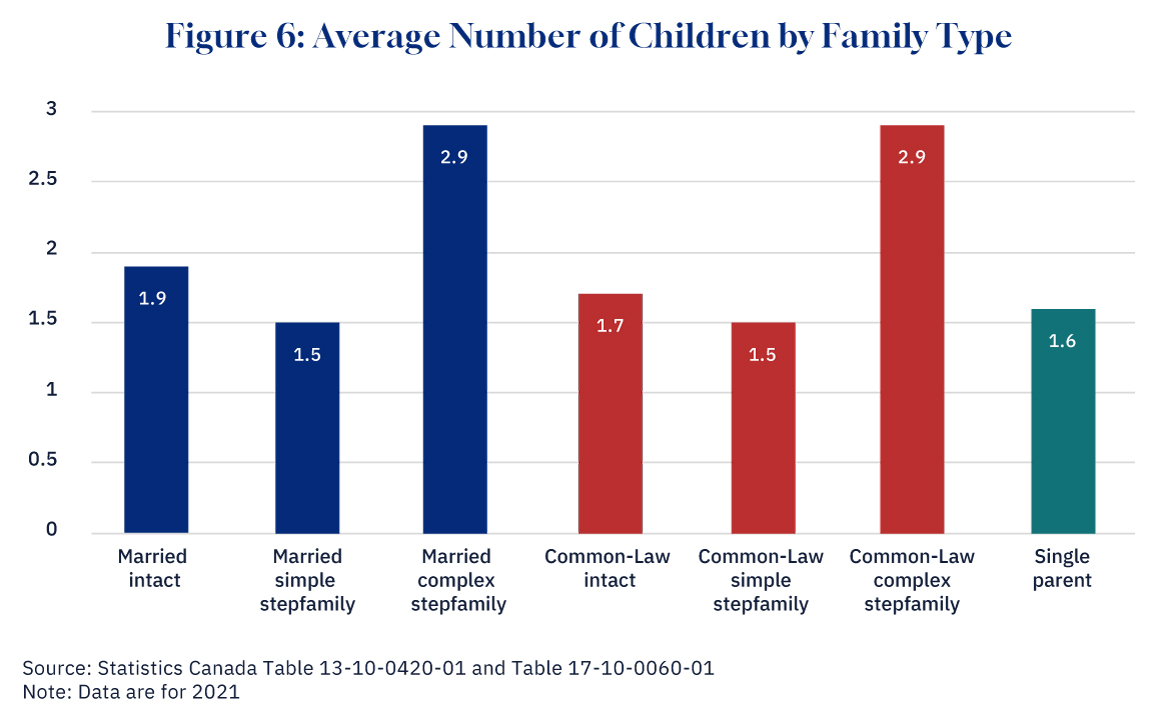

Are married couples likely to have more children than unmarried couples or single parents? This seems a relevant question to ask given the significant decline in Canada’s fertility rate, which is now the lowest in our history. Unfortunately, we don’t have data on fertility rates by family structure, because data on the common-law status of the parents isn’t collected at birth. However, we do have data on family sizes by family type. These are shown in Figure 6 below.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The data show that intact married couple families have somewhat more children than intact common-law couples: 1.9 children per family for married couple families compared to 1.7 for common-law couple families. When it comes to stepfamilies the average number of children is similar for both married and common-law couples: 1.5 for simple stepfamilies and 2.9 for complex stepfamilies. The higher average number of children in complex stepfamilies arises partly because partners are often bringing children from both previous relationships, and partly because they have gone on to have children in this new relationship. By definition, a simple stepfamily would only have children from one of the previous relationships.

The average number of children in single-parent families is only 1.6, similar to that in simple stepfamilies and common-law couple families. Obviously, single parents are much less likely to have additional children, although the parent may have more children once he or she has a new partner and is no longer in a single-parent family.

Overall, these data seem to suggest that married couples have higher fertility rates than common-law relationships, although the difference isn’t large. Whether this difference is because marriage makes people more likely to want children, or because people who want children are more likely to get married is of course hard to say without conducting an in-depth experimental study.

International comparisons

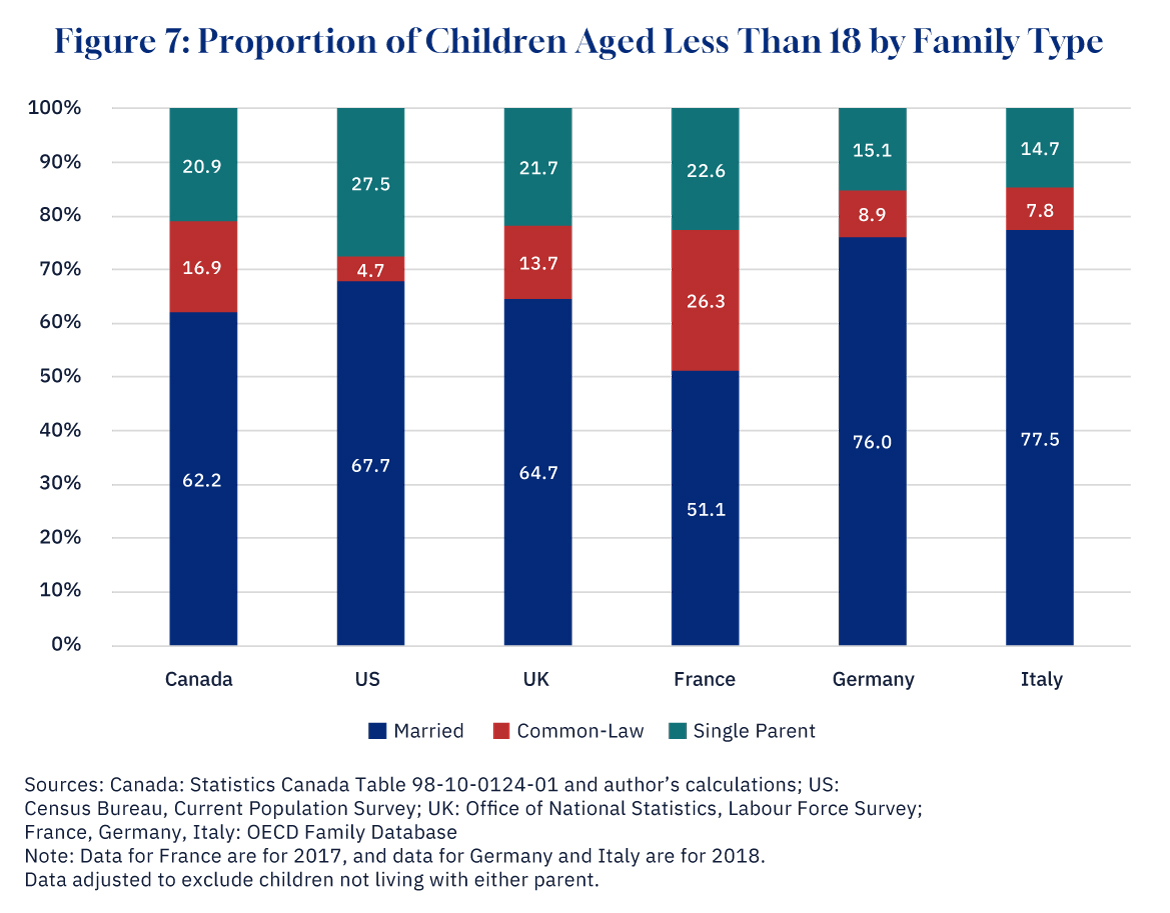

We now look at how Canada compares to five other G7 countries: the U.S., the U.K., France, Germany, and Italy. (Comparable data were not available for Japan). Because these other countries report data for children aged less than 18, we have adjusted the Canadian data to match. Beginning with the U.S. and the U.K., two countries that are culturally quite similar to Canada, we can see from Figure 7 that Canada has a smaller share of children in married couples: 62.2 percent compared to 64.7 percent for the U.K. and 67.7 percent for the U.S. The comparatively low proportion for Canada reflects the greater popularity of cohabitation: 16.9 percent of Canadian children under 18 are in common-law couples, compared to 13.7 for the U.K. and only 4.7 percent for the U.S.

This high proportion in Canada is entirely driven by Quebec: without Quebec, the proportion of children in common-law families would be lower than the U.K., although still higher than the U.S. When it comes to single-parent families, Canada has a lower proportion of children in this family type, with only 20.9 percent compared to 21.7 percent in the U.K. and 27.5 percent in the U.S. The high proportion of children in single-parent families in the U.S. is driven by the Black population, for which the proportion is slightly over 50 percent.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Turning now to the three continental European countries, we see that France has a significantly higher proportion of children in common-law relationships—26.3—than any of the other countries. This proportion is similar to, although slightly lower than, the 35 percent of children in common-law couples in Quebec. In both cases the retreat from marriage reflects societies that have, officially at least, rejected the Catholic church and embraced secularism, although it is notable that it is still the case in both places that more children live in married couples than in common-law couples. The proportion of children in single-parent families in France is 22.6 percent, only a little above that in Canada or the U.K.

In contrast, both Italy and Germany are more traditional, with 76 percent (Germany) and 77 percent (Italy) of children in married-couple families. In both countries, the proportion of children in common-law families is much lower than in France, the U.K., or Canada, although somewhat above the U.S. The proportion of children in single-parent families is much lower: around 15 percent for both countries, compared to over 20 percent for the other four countries.

Overall, when we look at other countries, Canada is on the low side when it comes to children in married-couple families, largely owing to the popularity of common law relationships in Quebec. However, the proportion of children in single-parent families is about average, lower than in the U.S., about the same as in the U.K., and France, but higher than in Germany and Italy.

Key takeaways

Canadians have every reason to care about the kinds of families that children grow up in. As we saw in the introduction, children who grow up with both their original parents do better across a whole range of life outcomes. What we see in the data is a gradual erosion in the proportion of children who grow up in these kinds of families. In 2021, only 58 percent of children lived in intact married-couple families, and many of these children will see their parents split up before they attain adulthood themselves.

Looking across Canada, the traditional married couple family is, unsurprisingly, most prevalent in Alberta and least prevalent in Quebec, although the proportion of children in single-parent families is higher in several of the maritime provinces than in the other provinces, probably reflecting their more rural nature. The territories are somewhat apart, with a significantly higher proportion of children in single-parent families, and significantly fewer in married-couple households.

Internationally, Canada has somewhat fewer children in married-couple families than the other G7 countries for which we have data, but the proportion of children in single-parent families is in the middle of the pack.

Thus, while there is no reason to panic about the state of two-parent families in Canada, there is cause for concern. Simply increasing monetary benefits to children will fail to deal with many of the underlying drivers of poor outcomes for children, such as the absence of a paternal role model. Policymakers need to think about what policies can encourage families to stay together and so provide the best possible environment for children to thrive. That debate is now very active in the U.S., and we in Canada need to have our own debate if we truly want to improve life for Canada’s children.

Tim Sargent holds a Ph.D. in Economics from the University of British Columbia and is the Domestic Program Director at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.