This article originally appeared in the Ottawa Citizen.

By Charles Burton, April 27, 2024

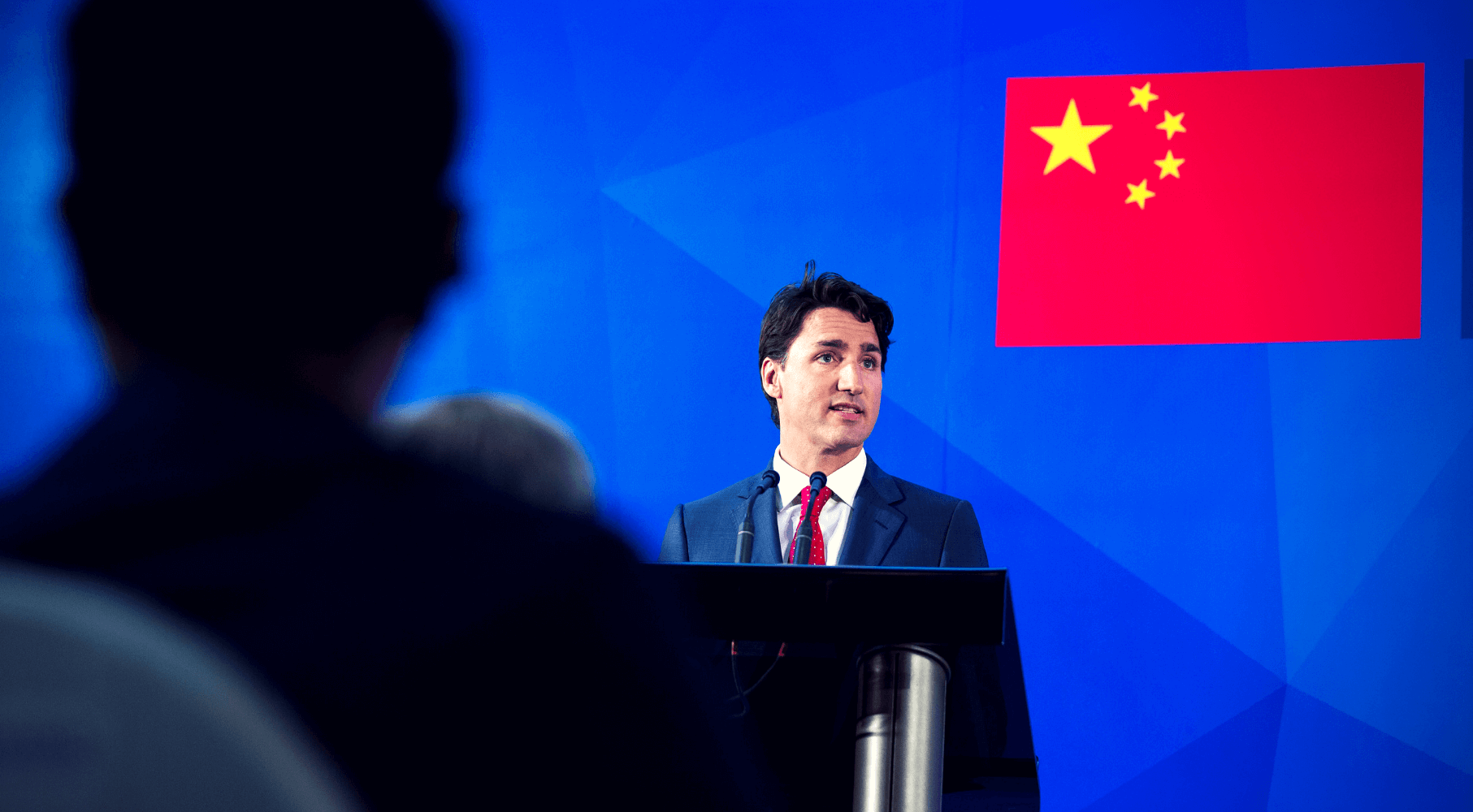

Many people would sense that Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was reaching for the race card last week when he cited the Second-World-War internment of thousands of Japanese- and Italian-Canadians as a reason why his government won’t be introducing new transparency laws — notably a Foreign Influence Registry Act — any time soon.

The prime minister’s observation, made during a press conference, follows an earlier, similarly illogical claim by Sen. Yuen Pau Woo that such legislation is designed to instigate an upsurge in racism against Canadians of Asian heritage.

These comments only deepen the impression that the government is ultra-sensitive about introducing any new procedure that would scrutinize relationships between senior Canadian politicians or business leaders and the Chinese Communist regime.

Political interference scandals that have been exposed in the United Kingdom and Australia demonstrate how China operates, and that influential Canadians who curry favour with the PRC regime, by urging the federal government to implement policy toward China that favours Beijing’s interests, could be doing so out of monetary or other self-interest.

In assembling its sphere of influencers, Beijing targets occupations that retired politicians and senior civil servants tend to move to, after careers spent serving the public trust. These could be people who are compensated by the Chinese regime through board memberships or other paid associations; or who receive income from Canadian companies that do business with China; who are associated with law firms who represent Chinese firms or Canadian firms who do business with the Chinese regime; or indeed who receive income from Canadian public policy think-tanks that in turn are funded by China-associated sources such as Canadian companies who do business with the Chinese regime.

Obviously, the ability of these Canadians to continue receiving benefits from Chinese sources will not be helped by anything that encourages public support for policies aimed at squelching the malign activities of Beijing’s agents. In the face of credible reports of illegal activities overseen by Chinese diplomats in Canada, they keep their own counsel, be it about election interference, Chinese “police stations,” military researchers entering our country on falsified visa applications whose mission is to obtain sensitive Canadian technologies, or harassing Canadians including those of Uyghur and Tibetan origin who speak their minds about China’s human rights violations.

Pleasing their Chinese patrons, some of these Canadian beneficiaries go on public record to insist that PRC policy to Uyghurs does not meet the criteria for “genocide,” that Huawei 5G presents no security threat to Canada, that government scrutiny of Chinese state acquisitions of Canadian high tech or natural resources is tantamount to racism, or that we should simply accept China’s claims over Taiwan and stop our freedom of navigation exercises in the South China Sea.

They seek to assuage public concerns by observing that relations with the PRC are “complicated” and “not black and white,” that the federal government should pursue a longer-term relationship with Beijing that is more “mature and sophisticated.” There are differences in values and ideologies, but Canada and China can collaborate in areas of mutual interest suggested by China.

A favourite diversion is to shrug off the U.S. and PRC as equally disruptive globally superpowers, and suggest that Canada must prepare for China’s inevitability rise and the decline of the West. Under Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s geostrategic program of the “community of the common destiny of mankind,” Canada can thrive in a China-led future. But we need to show goodwill and understanding to China now, forgive the Kovrig and Spavor hostage diplomacy, and disassociate Canada from any multilateral Indo-Pacific strategy that would constrain China’s rightful rise to comprehensive power on Chinese terms.

In a democracy, expressing perspectives on Canada-China relations, as articulated above, is what our liberal values and freedom of expression must protect. But democracy only thrives in openness and transparency.

The Foreign Influence Registry Act is simply about getting people who receive benefits from a foreign power to declare it publicly, but it appears that some respected senior Canadian influencers may have something to hide in this regard. Whether they have a conflict of interest in supporting Beijing’s purposes in Canada can be better assessed if we can simply follow the money.

Charles Burton is senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, non-resident senior fellow of the European Values Center for Security Policy in Prague, and former diplomat at Canada’s embassy in Beijing.