The Trudeau government’s deficit is increasingly driven by deliberate choices to spend more than it collects in revenues, writes Sean Speer.

The Trudeau government’s deficit is increasingly driven by deliberate choices to spend more than it collects in revenues, writes Sean Speer.

By Sean Speer, March 18, 2019

The details of the 2019 budget are spilling out in advance of Finance Minister Bill Morneau’s final budget speech before the October election.

The leaks point in the direction of an ongoing predisposition to large-scale spending growth. It sounds like we can anticipate new funding for broadband infrastructure, skills training, and various other government priorities.

The anticipation is that any positive revenue growth relative to the Fall Economic Statement will be more than offset by new and rising spending in the government’s final, pre-election budget.

It is not much of a surprise, of course. It is now abundantly clear that the government’s incoming commitment to control federal spending and minimize the deficit was at best poorly considered and at worst a politically-driven invention.

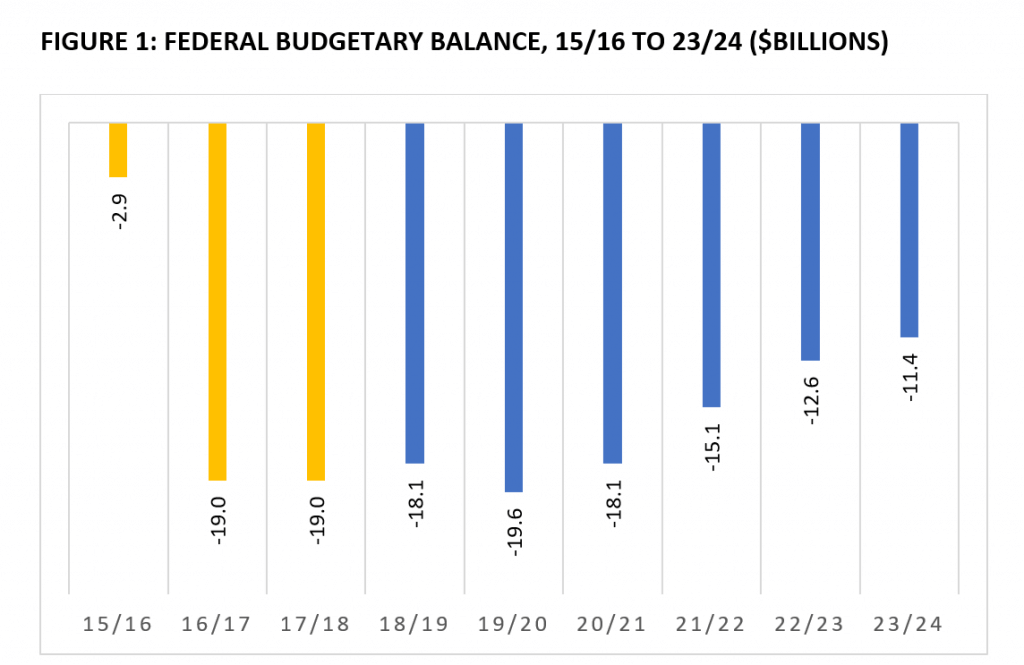

Early plans to run $10-billion deficits for three years and return to a balanced budget in 2019-20 have long been superseded (see Figure 1) – though the promise remains awkwardly codified in Minister Morneau’s mandate letter on the Prime Minister’s website.

And the source of Ottawa’s larger and longer deficit? A new report by the Laurentian Bank points increasingly to deliberate spending choices on the part of the government.

The author(s) recognize that a portion of Ottawa’s deficits in 2015/16 and 2016/17 was driven by “cyclical” factors such as the decline of oil prices in 2014 and 2015. MLI research and commentaries have made similar observations.

But increasingly the federal deficit is “structural” by which the author(s) mean that there is a fundamental gap between government revenues and expenditures in “normal” economic circumstances. The report estimates in fact that 90 percent of the 2017/18 deficit was structural.

Put differently: the Trudeau government’s deficit is increasingly driven by deliberate choices to spend more than it collects in revenues.

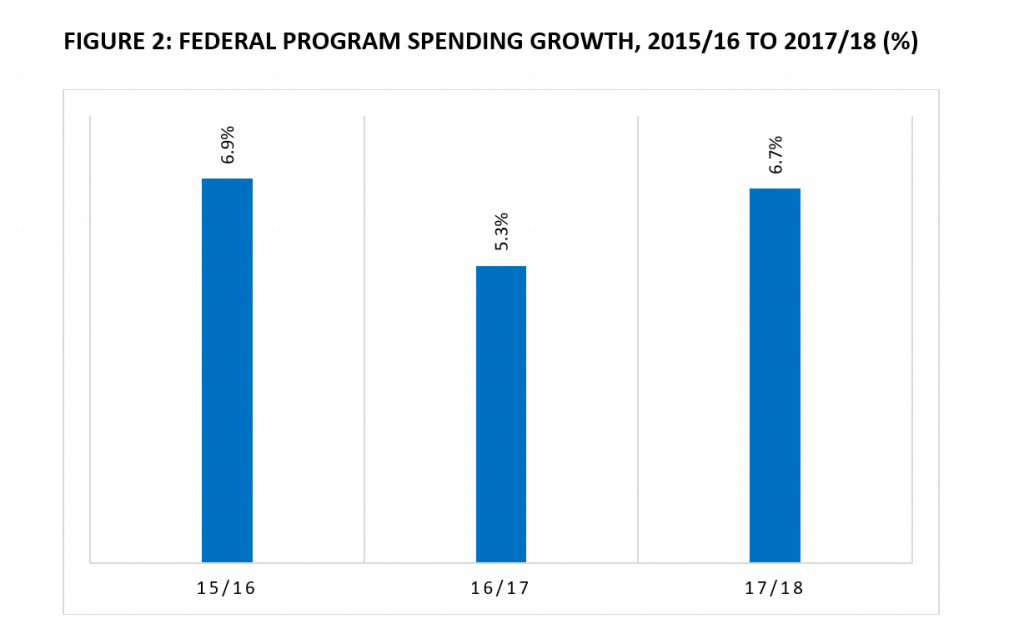

It should not necessarily come as a surprise. Remember the government has ramped up spending by an annual average of 6.3 percent over its first three years (see Figure 2). And even as revenue projections have improved, the deficit has remained unchanged or even worsened due to this rising spending.

The problem, of course, is that a structural deficit could deteriorate if economic conditions weakened.

As the report points out:

“Under the pessimistic scenario of a recession, the federal government would incur a larger deficit with both a cyclical and structural component, similar to 2009 and 2015. This would put significant pressure on public finances at a time of high economic uncertainty and financial markets volatility.”

Others have sought to estimate what budgetary effect would be if we experienced a recession. Depending on its severity, the deficit could jump to over $34 billion and that is before any invariable stimulus response on the part of the government.

Mr. Morneau has, by and large, neglected the deficit in his three previous budget speeches. The previous balanced budget commitment has been de-emphasized. And talk of so-called “fiscal anchors” has subsided.

The result is a structural deficit that exposes Canada’s budgetary position to downside risks. Now would therefore be a good time to change course and reaffirm the government’s commitment to its previous budget pledges. Early signs do not look promising in this regard. We will know soon.

Sean Speer is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.