By Kei Hakata, April 3, 2023

This is a bold step by a gentle country. Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (IPS), launched in November 2022, pointed to China as “an increasingly disruptive global power” and maintained that “Canada will, at all times, unapologetically defend [its] national interest, be it about the global rules that govern global trade, international human rights or navigation and overflight rights.”

As Canada infuses geostrategy into its foreign policy, the Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau clarified Ottawa’s stance, which some have already dubbed “historic.” Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly rightly said, “Canada is a Pacific country […] the Indo-Pacific region is part of Canada’s DNA.” By confronting China’s revisionism, Canada has demonstrated its determination to remain present and relevant in an increasingly critical region.

As a much-awaited document, Canada’s IPS is the culmination of its trusted engagement with Asia and desperate struggle with the People’s Republic of China. Accompanied by a five-year program of $2.3 billion covering a wide range of activities, the IPS is a departure from Ottawa’s past China policy and represents an effort to counterbalance China’s weight. The IPS was introduced after the COVID-19 crisis and the war in Ukraine brought a clear strategic perspective. Indeed, as Canadian analysts pointed out, the IPS is a work in progress, and how Canada’s long-term commitment will materialize remains to be seen.

Absent in the conversation for many years and coming after Quebec’s foray, Canada is a latecomer to the Indo-Pacific formulation compared to other lynchpin states, such as Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. This lag is understandable given Canada’s distance from the geopolitical epicentre of the Indo-Pacific. Except for cases of Chinese influence operations inside Canada or those involving Canadian citizens (notably the “two Michaels”) detained in China, Canada does not typically face Beijing’s provocations around its borders. The inertia of the Pearsonian tradition may also have hindered a tough posture in terms of its foreign policy.

In many regards, Canada’s trajectory resembles those of Australia and Japan. For decades, Canada has enjoyed peace and prosperity in the US-led international order. However, China’s growing bellicosity has challenged Canada’s peaceful existence. As was true for Canberra and Tokyo, Ottawa’s Indo-Pacific embrace was bound to occur sooner or later.

Like Australia and Japan, Canada has aimed to present itself as a “good citizen” of what many used to call the international community. There is little doubt that the dividends of a stable international order allowed this diplomatic posture. Therefore, Ottawa could efficiently use the United Nations and other multilateral forums as its preferred venues, and it worked. Canada has been an influential soft power in the international arena since World War II.

UN peacekeeping operations, initiated by Lester B. Pearson, responded to the needs of the era. The Ottawa Convention on Anti-Personnel Mines, led by Lloyd Axworthy, illustrated Canada’s skillful diplomacy, although it was a product of a time when policy-makers worldwide, including those in threat-ridden Japan, were still naïve. The “protection of civilians in armed conflict,” an initiative introduced at the UN Security Council in 1999, is Canada’s valuable contribution to human security. The Responsibility to Protect (R2P), which few now discuss, exemplifies Ottawa’s diplomatic activism.

In the “good old days,” Canada could comfortably exploit its pacifist niche. Now, the country must grapple with the harsh reality of a multipolar world in which its cherished agendas are not necessarily relevant or easily accepted. In this strategic dilemma, the premise of Canadian diplomacy is falling apart. How will the IPS, with its “Canadianess,” unfold? Can Canada maintain its activist position by pursuing a rule-based Indo-Pacific order? Should Canada change its diplomatic identity?

Obviously, because the IPS offers possibilities for different postures, political input, including further budget allocations, will determine its outcome. Thus, the direction to which its core China policy (and its engagement with Taiwan) will go depends on its actual implementation, as well as its defence policy. Despite these uncertainties, we can cautiously predict the eventual challenges.

The IPS wisely articulates economic elements, such as the expansion of Canada’s trade network and further engagement with the member states of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Such policies will not be controversial because Canada will gain much from trade if it is conducted carefully. Canada’s raw materials and agricultural products are important assets, as its trade ties with Japan prove. People-to-people relations with the Indo-Pacific region, from which many migrants to Canada come, is also a smart way to promote Canada’s public diplomacy. It is likely that many Canadian citizens will concur with and participate in these diplomatic efforts.

By contrast, Canada’s military expenditures and defence cooperation with like-minded states, either bilateral or minilateral, may require a boost. An allocation of $492.9 million pledged under the IPS for the “Enhanced Defence Presence and Contribution” does not seem to match the real needs. Even with the war in Ukraine, Canada’s military spending remains one of the lowest as a percentage of GDP among NATO members. Further, Zeitenwende will be required by the Canadian polity and society to reverse what has been accepted as a norm for many decades.

Undoubtedly, there are advantages to partnering with other Indo-Pacific states, such as Australia and Japan. Concerted efforts will safeguard Canada’s peacebuilder identity, highlight its international standing, and increase its strategic autonomy vis-à-vis the US. For example, Canada and Japan concluded an “Action Plan for contributing to a free and open Indo-Pacific region” in October 2022. Such partnerships can foster Ottawa’s international commitment — albeit differently from its past — and promote the role of “good cop.”

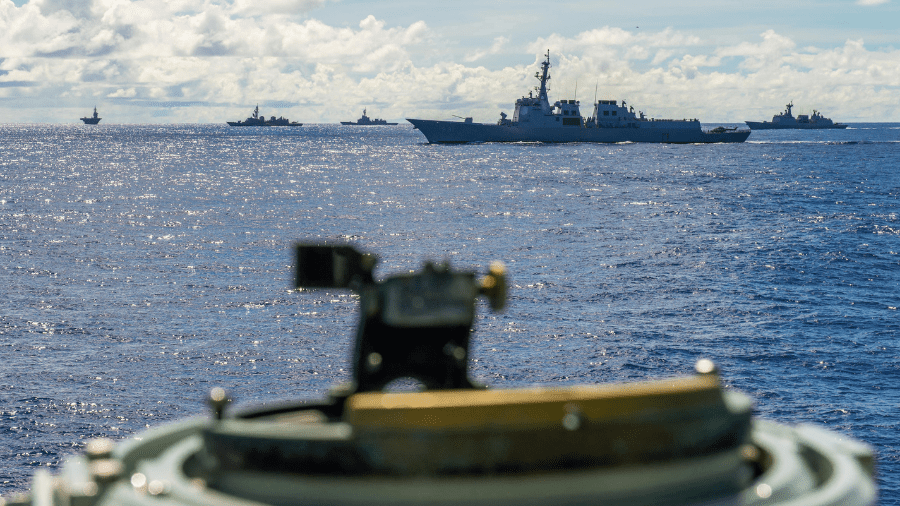

To secure a rules-based maritime order, the Royal Canadian Navy actively participated in various military exercises and operations with US forces, which became more effective peacekeeping tools than UN-led ones. Canada should perhaps moderate its affection for the UN and judiciously explore minilateralism, which has been underutilized thus far. Ottawa’s reported proposal for a “North Pacific Quad” of Canada, Japan, South Korea, and the US reflects this direction, though South Korea, which had grabbed the Japanese island of Takeshima, may hardly identify as an espouser of international law.

As Canada increases its Indo-Pacific presence, the question of prioritizing various military engagements necessarily arises. The Indo-Pacific geopolitical centre areas, such as the South and East China Seas and Taiwan Strait, are far from Canada’s shores. However, this region holds special meaning for Canada’s attachment to the rule of law, begging the question of resource allocation, as the Arctic region is equally crucial for Canada’s defence and presence. These conundrums can only be resolved by increasing the defence budget.

It also remains questionable whether Ottawa’s emphasis on the values of human rights and democracy, including its feminist agenda, is realizable in a more complicated international environment. This question applies particularly to the current Liberal government. Many governments in developing and emerging states now feel empowered against the background of the collective “Global South.” If Global Affairs Canada, under pressure from domestic constituencies, wants to advocate Canadian values, it must embrace pragmatism. Nonetheless, Canada must not compromise its core values vis-à-vis China, as Joly declared.

The “internalization” of the Indo-Pacific or China strategy will face practical challenges. For Beijing, Canada has operated as “a friend in America’s backyard” and, as such, it consciously attempted to dominate Canada in various aspects. To counter PRC interference, the Canadian government must take tough measures to ban foreign political financing and unregistered lobbying on Canadian soil. Disruptive activities by China’s United Front on Canada’s Chinese diaspora must be annihilated.

The whole task is daunting for Canada, which must grasp the speed of strategic developments. Despite its tough rhetoric in the IPS, Canada’s “good cop” disposition may also induce it to deal with leaders in Beijing in an appeasing way. Policy-makers in Canberra, Tokyo, and Washington must carefully examine how Ottawa’s China policy evolves.

At the very least, Canada is stepping up its foreign policy readjustment with a foray into the Indo-Pacific. True to its national character, Canada has proved its strength by exhibiting resolve. The country has also vindicated freedom by defending its sovereignty and democracy. Canada’s Indo-Pacific awakening may only be a prelude to a demonstration of its resilience.

Kei Hakata is a professor at Seikei University in Tokyo, Japan. He specializes in international politics and security affairs focusing on the Indo-Pacific. His latest book, co-edited with Brendon J. Cannon, is Indo-Pacific Strategies: Navigating Geopolitics at the Dawn of a New Age (Routledge).