By Adam Zivo, December 20, 2022

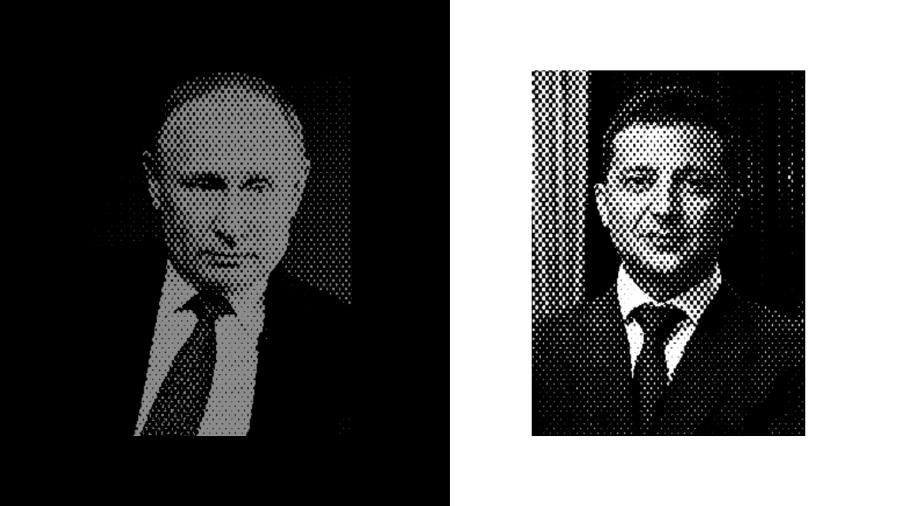

Each year, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute recognizes an individual who, by having an immense impact on Canadian federal policy, deserves the title “Policy-maker of the Year.” The recipient of this title need not be a force for good – in 2019, the title was given to Xi Jinping. This year, the title goes not to one, but two people – Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine revolutionized the global policy landscape, something which both Putin and Zelenskyy bear responsibility for. Without Putin, there would have been no invasion to begin with – but, without Zelenskyy’s unexpectedly effective leadership, it’s likely that Ukraine would have capitulated last spring, destabilizing the world in an entirely different way.

It’s because of these two leaders that the war has continued for as long as it has. The invader refuses to halt his brutal aggression, while the defender refuses to abandon his nation to re-colonization. An unstoppable force meets an immovable object.

Amid this war of attrition, the world has changed. Europe is now remilitarizing, putting pressure on NATO members to boost their military budgets. Putin’s embrace of energy warfare has forced European nations to reconsider their dependence on Russian liquified natural gas (LNG) – a development that has global economic ramifications.

Western states have admirably coordinated on sanctions that have dented, though not crippled, the Russian economy. Relatedly, substantial aid packages have been sent to Ukraine, allowing the country to stave off defeat. Yet these measures have been imperfectly applied, revealing difficult tensions within the international community.

All of these policy developments impact Canada – but not necessarily in ways that reflect well on the country. If anything, Russia’s war in Ukraine has underlined the federal government’s reluctance to show leadership on the world stage.

Increased defence spending

NATO members are now significantly increasing their military spending in anticipation of future conflict. Eastern European states have predictably led the way, driven by the reasonable fear that, should Ukraine fall, they will be invaded next. Poland, for example, pledged to increase its military spending from 2.2 percent of GDP to 3 percent by 2023, with an ultimate goal of 5 percent – an aggressive target that may position the country as one of Europe’s leading military forces.

France hiked its defence budget by an additional 7.5 percent (or US$3 billion) for 2023, reaching 2 percent of GDP, while the United Kingdom pledged to increase defence spending to 2.5 percent of GDP by 2026 (up from 2.1 percent currently). Even Germany, which has been remarkably tepid in its approach towards Russia, has committed to substantially increasing its military budget, setting the country’s defence spending on track to reach 2 percent of GDP within a few years.

Canada has chronically underinvested into defence (regardless of which party governs), irritating American policy-makers and leading them to occasionally chide us for perceived freeloading. However, in 2017, the federal government committed to a 10-year, 70 percent increase to defence funding. While that figure sounds impressive, Canada is only playing catch-up. In 2021, only 1.5 percent of Canada’s GDP was spent on defence – a 50 percent improvement from 2014, but still one of the lowest rates in NATO.

In response to the war in Ukraine, the federal government committed $8 billion over five years to defence. That’s only about a 5 percent increase in the defence budget, a paltry investment compared to what our allies have pledged, which is expected to bring Canadian defence spending to only 1.6 percent of GDP. The new funding commitment is arguably only a token gesture.

Canada’s unserious approach to defence is, in many ways, a product of its geography. Isolated from its adversaries by vast oceans, Canada’s only real security threat, at least for the foreseeable future, will be maintaining its Arctic sovereignty – an issue that, unbeknownst to many, actually intersects with the war in Ukraine.

Global warming is opening up valuable new shipping channels in Canada’s North, causing security experts to worry that Russia and China will try to assert themselves there. Canada’s grip over the North has always been tenuous, after all.

Securing the North will be an expensive endeavour. For example, the Canadian Coast Guard is spending $1.5 billion to build just two Arctic coast guard ships. Lifetime operating costs for these ships will also be in the billions.

Rebuilding Canada’s naval strength is important, but it’s equally important to weaken adversaries who might gnaw at the Canadian North. This is where Ukraine comes in. The war in Ukraine has crippled Russia’s military capabilities. Should Putin concede defeat and retreat from Ukrainian lands, Russia’s capacity to project force into the Arctic would be hampered for a generation. China would remain a threat to our Arctic sovereignty, but resisting one adversary is easier than resisting two.

One would expect Canada to provide more robust aid to Ukraine, given these geopolitical considerations. However, as of November this year, total Canadian aid to Ukraine amounted to only $3.9 billion – $1 billion in military aid and $2.9 billion in humanitarian aid.

That may sound like a lot, but it amounts to only 0.6 percent of the federal government’s 2021 expenditures, or 0.15 percent of total GDP.

Canada’s humanitarian aid to Ukraine amounts to 35 percent of our international development budget, so it would be unfair to criticize that aid as insufficient. Canada also recently announced the creation of $500 million on “Ukraine Sovereignty Bonds,” which will allow average Canadians to directly support the Ukrainian government. Insofar as non-military support goes, Canada seems to be doing its part.

However, Canada grossly underperforms on military aid. The military aid provided so far is equal to only 4 percent of our 2021 defence budget and is 75 percent lower than what the United States has given on a per capita basis. It’s arguable that our underwhelming military aid reflects our propensity to freeload on defence.

Sanctions

Like many western countries, Canada applied sanctions against Russia this year, prohibiting Canadians from conducting business with Russian government-affiliated entities, such as banks, state-owned enterprises.

However, Canada and Russia’s trade relationship is miniscule. Last year, Canadian imports from Russia amounted to only $2.14 billion (0.35 percent of Canada’s total imports), while exports amounted to only $0.66 billion (or 0.1 percent of total Canadian exports). Canadian sanctions are thus insignificant to both sides.

Canada has also sanctioned high-level Russian officials, leading the Kremlin to retaliate with their own sanctions against Canadian individuals. The tit-for-tat sanction battle between Canada and Russia is more symbolic than substantive. This seems especially true from the Russian side, considering that sanctioned Canadians include figures of questionable geopolitical importance, such as Margaret Atwood and Jim Carrey.

There was one instance this year in which Canadian sanctions could have made a difference. In July, Russia claimed that it was unable to provide LNG to Germany through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline until it regained custody of a key turbine. This turbine was owned by Siemens Energy, a German-based multinational conglomerate, and had been sent to Montreal for repairs by Siemens Canada.

Canadian sanctions should have blocked the return of the turbine, as they prohibit the export (or re-export) of items that may benefit the Russian energy sector – even if the commodity first goes to a third party that acts as an intermediary (in this case, Germany). Siemens Canada is legally a Canadian entity and is therefore beholden to Canadian law.

The fact that the turbine was owned by a German entity is irrelevant. Foreign entities cannot send sanctioned items to Canada for repair and then later cry about ownership. Were it otherwise, what would prevent third parties from sending Iranian weapons to Canada for refurbishment, for example? International supply chains do not trump national law.

Seemingly trapped in Canada, the turbine became the centre of an international controversy. The Germans, still deeply dependent on Russian LNG, begged Canada to permit its return. Many suspected that Putin was trolling the Germans and that, even if the turbine were to return, some other pretext would be discovered to block gas exports.

This suspicion was ultimately proven right. The federal government caved to German pressure and granted an exemption for the turbine, which was then returned to Germany. Russia subsequently claimed that the turbine was unusable and LNG exports via Nord Stream 1 remained blocked.

The debacle showed how unseriously Canada takes its sanctions. The moment these sanctions lead to real costs, and potentially have a real geopolitical impact, the government abandons them. Why even enact sanctions in the first place?

The embassy debacle

In May, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visited Kyiv to announce the reopening of Canada’s embassy in Ukraine. Like many other countries, Canada had shuttered its embassy due to the war and relocated associated staff. By the time Trudeau made his announcement, several other countries, including the United States, had already re-opened their embassies.

However, in August it was discovered that the embassy had not actually been reopened and had stayed shuttered. Those visiting the embassy were given an email which they could direct inquiries to.

The government claimed that the embassy’s closure was due to ongoing security concerns, but this explanation was wildly implausible. Seemingly every other western embassy had safely resumed operations in the capital. Throughout the summer, Kyiv was largely insulated from the war and residents lived relatively normal lives – a fact that was widely reported on in the media.

It was simultaneously reported that Canada abandoned its Ukrainian embassy staff at the outset of the war – despite knowing that, if Ukraine were to fall, these staff would likely have been hunted and either tortured or killed. This information was apparently leaked to the Globe and Mail by disgruntled Canadian diplomats.

In the absence of official support, Canadian embassy staff had to personally fundraise to help their Ukrainian co-workers. The amount they raised, $90,000, was commendable but paled in comparison to the support that should have been provided by the government.

Weeks before Putin’s full-scale invasion, allies had provided the Canadian government with intelligence reports warning that Ukrainian embassy staff would be targeted. Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly claimed that she and her department were unaware of such reports. It was another implausible claim that contradicted the aforementioned diplomatic sources that leaked the story.

These debacles undermined Canada’s diplomatic credibility. How can allies trust Canadian diplomacy if we lie about whether our embassies remain open or closed? How can we build trusted local networks if we show a willingness to throw local staffers to the wolves?

By all rights, there should’ve been a public inquiry into how these incidents were allowed to happen – and, relatedly, concrete measures should’ve been put into place to ensure that such mistakes are not repeated. Instead, the government refused to take any accountability for its shortcomings and repeatedly made wildly implausible claims to absolve itself of responsibility for its failures.

Energy politics

Until this year, much of Europe was dependent on Russian LNG – a dependency that Russia gleefully weaponized to unsuccessfully pressure European states into abandoning Ukraine.

The effects of this energy warfare were clearest in Germany. German policy-makers had spent a decade fostering a nation-wide addiction to cheap Russian LNG, despite being loudly warned about the geopolitical vulnerabilities this addiction would create. In 2006, for example, Poland compared the opening of Russia’s Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Hitler’s Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with Stalin.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine this February, Germany was remarkably reluctant to offer Ukraine any support beyond cheap rhetoric. Germany has consistently dragged its feet with aid – for example, in April it promised to provide weapons to Ukraine but, in the ensuing months, failed to follow through, leading Kyiv to accuse Berlin of duplicitousness.

In November, former British Prime Minister Boris Johnson alleged that, at the outset of the war, German political leaders had actually hoped for a quick Ukrainian defeat, so as to minimize disruptions to Germany’s economy. If true, then Poland’s 2006 invocation of the Molotov-Ribbentrop was apt, in that Germany seems content with the dismemberment of its eastern neighbours if it enriches the German economy.

But Germany isn’t the only disappointment here. When it comes to energy politics, Canada seems equally complacent with empowering dictators.

For years, critics have pointed out that throttling Canadian oil and gas won’t reduce global emissions, but rather will only increase reliance on energy exports from authoritarian states. Putin’s weaponization of LNG has brutally validated this analysis.

In this way, Canada is somewhat complicit in Ukrainians’ suffering. Had Canada been a larger energy exporter, European states would’ve been able to diversify their energy suppliers, reducing Russia’ economic leverage and energy revenues. Yet Canadian policy-makers espoused a particularly narrow-minded and myopic form of environmentalism that ignored the geopolitical dimension of energy policy.

One would have hoped that the war in Ukraine would’ve changed things – but the federal government obstinately refuses to change course.

In August, German chancellor Olaf Scholz visited Canada to discuss turbo-boosting Canadian energy exports – he called Canada a “partner of choice” and said, “we hope that Canadian LNG will play a major role in this.”

The Trudeau government responded by arguing that there was no business case for developing Canadian LNG – a claim which industry players called absurd. Trudeau gave Scholz a tour of a wind-to-hydrogen facility in Newfoundland and, ultimately, the two signed an agreement that will allow Canada to export “green” hydrogen to Germany within a few years.

The problem is that, even in the best-case scenario, Canada has the capacity to produce only marginal amounts of green hydrogen. Green hydrogen is also expensive, which is why the European market for it is much smaller compared to natural gas.

Essentially, Canada declined to provide Germany any serious energy exports. In lieu of a real solution, the federal government offered the Germans an inferior, expensive form of energy that can only be produced in homeopathic quantities that cannot hope to address German energy needs.

In energy policy – as in defence spending, military aid, embassy policies, and sanctions – it seems that Canada is content with doing little while pretending to do a lot.

What to make of all this?

Russia’s war in Ukraine has obviously had a significant impact on the global policy landscape, which has inevitably bled into Canadian federal policy. Yet for all the public rhetoric about Ukraine, the federal government’s policy responses have been lacklustre. The federal government has repeatedly made grand claims about showing support – and yet failed to back up these claims with serious action.

Our defence budget remains dismal, and Ukraine-related budget increases have been relatively trivial. Our military aid is a fraction of what the United States has given. Our sanctions have amounted to little more than theatre, while our treatment of our embassy in Kyiv has been a tragi-comedy. We seem unable or unwilling to grasp the realities of global energy politics, and, rather than be frank about the trade-offs of environmentalism, have tried to peddle our “green” hydrogen as a serious energy solution despite all evidence to the contrary.

It’s clear that, though Zelenskyy and Putin have had a serious impact on Canadian federal policy, the impact has not been what many expected or wanted it to be. Rather than inspire real leadership among our policy-makers and political leaders, Russia’s war in Ukraine has, more than anything else, exposed a culture of complacency, as well as a preference for optics over substance.

Adam Zivo is an international journalist and LGBTQ activist. He is known for his weekly National Post column, his coverage of the war in Ukraine, and for founding the LoveisLoveisLove campaign. Zivo’s work has also appeared in the Washington Examiner, Xtra Magazine, and Ottawa Citizen, among other publications.