If we followed McCallum’s recommendations, once the Meng issue is resolved, Ottawa should resume its relationship with China as if the terrible human rights violations in China and the bad behavior were irrelevant. We cannot, as he suggests, put all these things aside, writes J. Michael Cole.

If we followed McCallum’s recommendations, once the Meng issue is resolved, Ottawa should resume its relationship with China as if the terrible human rights violations in China and the bad behavior were irrelevant. We cannot, as he suggests, put all these things aside, writes J. Michael Cole.

By J. Michael Cole, August 5, 2020

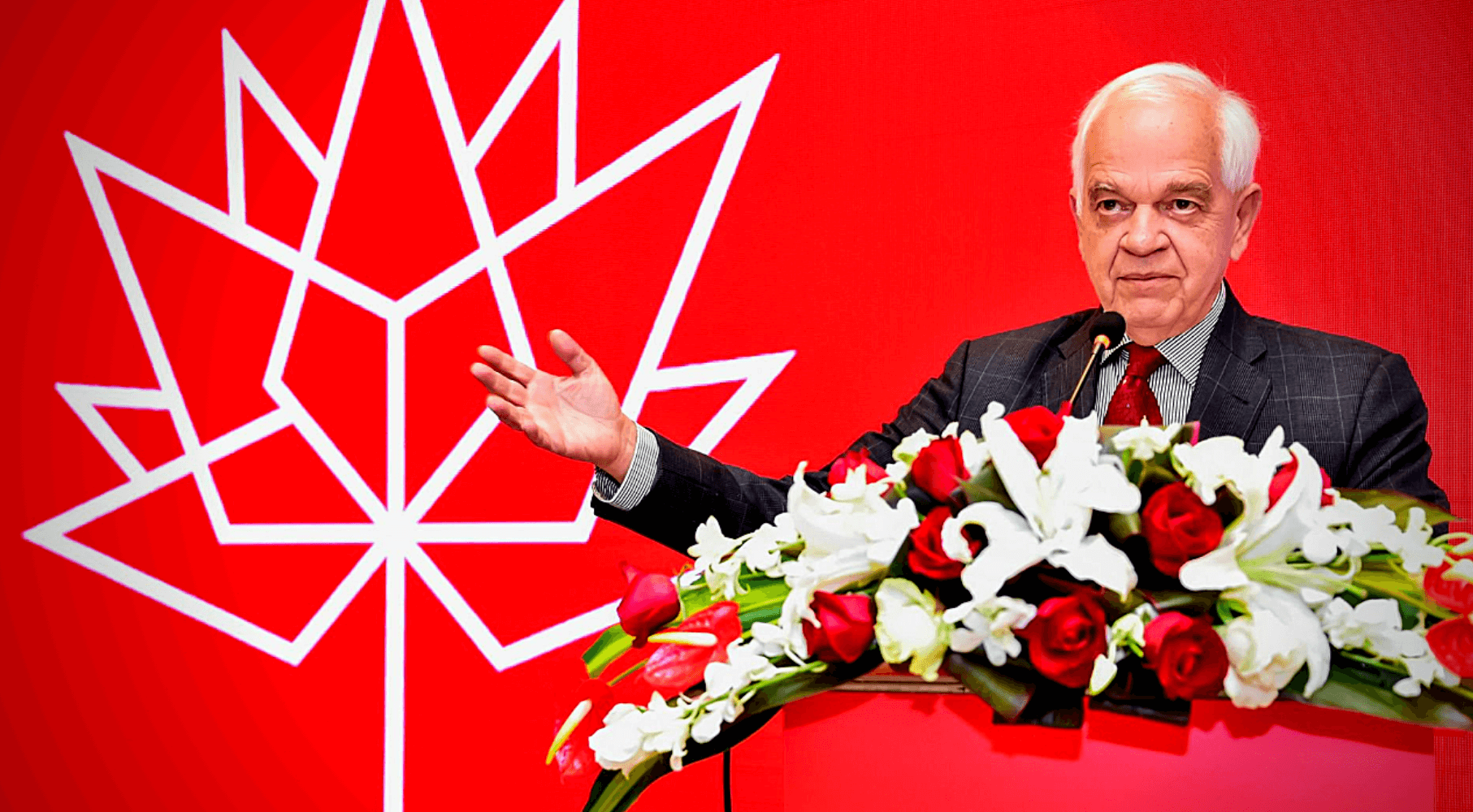

As frictions between the governments in Ottawa and Beijing continue to escalate, Canada’s disgraced former ambassador to the People’s Republic of China told an event organized by a Chinese immigration company that the troubles are only temporary because “Chinese people and Canadian people are good friends.”

While there is absolutely nothing wrong with the claim that the Canadian and Chinese people have a longstanding relationship, McCallum’s prognosis for the state of bilateral ties is downright wrong. In his view, the dispute is only a passing moment, the result of “substantial problems” arising from the detention of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou and the retaliatory kidnapping – this author’s wording, not the former ambassador’s – of two Canadian nationals, Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor.

In McCallum’s view, the problem is unlike that which pits the U.S. and its Asian rival, a contest for “top dog” status within the international community, and is therefore “less long-term in nature than the U.S. challenges with China.”

Although Canada, a middle power, will never be locked in a contest for supremacy with the Middle Kingdom, it is altogether wrong to argue that our problem with it isn’t equally long-term. The rise of a despotic regime with global reach – and our problem is fundamentally with the Chinese Communist Party, not the Chinese people – is a long-term issue for Canada. Kovrig, Spavor and Meng could all regain their freedoms tomorrow and the dispute would not go away—unless, of course, one choses to ignore, as Mr. McCallum appears to be doing, the rather inconvenient truths about the nature of the party-state apparatus in Beijing.

Canada, along with other democracies large and small worldwide, cannot continue to regard its relationship with the PRC as if it were a normal state. We cannot, as a country that sent thousands of men and women to their deaths fighting fascism and authoritarianism in the twentieth century, behave as if the CCP were not engaged in atrocities on multiple fronts.

This is a regime that is holding, in concentration camps in Xinjiang or as forced labourers in factories across China, as many as 1.5 million Uighur Muslims; destroying Christian churches; continuing its more than a half-century assault on Tibetans; silencing critics; threatening the military invasion of democratic Taiwan; breaking international law in the South China Sea; and exporting a model of governance, at the UN and within the developing world, that threatens to destabilize the very foundations of the global liberal order.

(Most assuredly, that order often has been observed in the breach by Western countries, failings which must be acknowledged. Nevertheless, the alternative that Beijing has been offering would arguably result in far more systematic human rights violations.)

Remove Kovrig, Spavor and Meng from the equation, and the CCP and its proxies would continue to steal our technology, to monitor and harass its diaspora in our cities, and to threaten and blackmail us whenever we do or say anything that doesn’t meet approval by the autocrats in Zhongnanhai.

If we followed McCallum’s recommendations, once the Meng issue is resolved – and its resolution would inevitably have to be on Beijing’s terms, with our side abdicating – Ottawa should resume its relationship with China as if the terrible human rights violations in China and the bad behavior were irrelevant. We cannot, as he suggests, put all these things aside because “economic interests will drive Canada and China to continue to work together,” or because “the last thing in the world Canadian universities would want to do would be to lose their 140,000 Chinese students.”

Actually, the last thing in the world that we, Canadians, should want is for our country, our government, to be complicit in the kind of atrocities that, at high cost, we and friends from Allied countries believed we had put an end to by defeating the Nazis and their murderous allies in Rome and Tokyo. We are better than this. Or we should be better than this, for our government has often demonstrated the unfortunate inclination to look the other way whenever new evidence of CCP wrongdoing has surfaced.

Given the severity of the threat that the CCP poses to our values, it is also imperative that we finally find ways to curtail the nefarious influence of the corporate sector on our foreign policy. This includes the long, ignoble train of former government officials who, like Mr. McCallum, are now putting personal material gain ahead of the nation’s best interests.

We need a principled foreign policy, one that aligns with other countries that are beginning to recognize that the CCP is the greatest political challenge of our times. That would also mean that Ottawa must further engage with Taiwan, a frontline country from whose experience we can learn very useful lessons on how to balance our economic interests with the need to defend our democracy and way of life. Surely our “good friends,” the Chinese people, would not take issue with that.

The question, then, is whether our “friends” are the Chinese people, or the CCP.

J. Michael Cole is a Taipei-based senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, the Global Taiwan Institute in Washington, D.C., and the Taiwan Studies Programme at the University of Nottingham. He is a former analyst with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service. His latest book, Insidious Power: How China Undermines Global Democracy, which he co-edited with Dr. Hsu Szu-chien, was released in July.