Ottawa’s support for Magnitsky legislation signals Canada is prepared to lead the charge on sanctioning human rights abusers, writes Marcus Kolga.

Ottawa’s support for Magnitsky legislation signals Canada is prepared to lead the charge on sanctioning human rights abusers, writes Marcus Kolga.

By Marcus Kolga, May 23, 2017

Canada took a gigantic leap last week toward realizing its self-identified role as a global human rights leader when Chrystia Freeland announced the government would back global Magnitsky legislation. When it passes, the legislation will empower the government to apply sanctions, including visa bans and asset freezes, against the torturers, jailers and murderers of activists around the world.

The five-year battle to adopt this straightforward, yet powerful, legislation has faced serious pushback from Russian, Chinese and Iranian regime supporters and their economic allies in Canada. Sadly, for Canadians, lurking over the brave human rights crusader that they see in the national mirror, is the dark shadow of foreign economic interests.

Since the end of the Second World War, Canadians have eagerly crafted an international self-identity that is dominated by the notions of peacekeeping and advocacy of global human rights. Human rights are part of Canada’s national narrative and its involvement in the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is at the centre of it.

Sadly, for Canadians, lurking over the brave human rights crusader that they see in the national mirror, is the dark shadow of foreign economic interests.

In fact, wording on the Global Affairs Canada website has endured unchanged for several elections, cabinet shuffles and four different prime ministers. The unchanged text in the human rights section declares that “Canada has been a consistently strong voice for the protection of human rights and the advancement of democratic values. This started with our central role in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1947-1948 to our work at the United Nations today.”

Yet Canada’s support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was as much of an uphill battle as the struggle to adopt Magnitsky legislation. As we Canadians proudly like to remind the world, the universal declaration was the result of the work of Canadian legal scholar John Peters Humphrey and former U.S. first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt.

In stark contrast to the lore that’s featured on the website, Louis St. Laurent’s government, in fact, did everything it could to stall, derail and avoid supporting the universal declaration in 1948.

When the final draft of the declaration was tabled at the committee stage, the Canadian delegation was among a handful, including the Soviet Union and those under its control, to abstain from supporting it.

Embarrassed by its closest allies, the United Kingdom and United States, for abstaining with the Soviets, the Canadian delegation voted to adopted the declaration when it was tabled at the Paris General Assembly in December, 1948.

As in the 1940s, the Trudeau government’s resistance toward adopting Magnitsky legislation threatened to align it with some unsavoury regimes. Former minister of foreign affairs, Stéphane Dion, lamented that Magnitsky legislation might antagonize Russia — and other states that abuse human rights — and threaten Canada’s limited interests in states ruled by those repressive regimes. As former Liberal leader Bob Rae has said, “we must not confuse engagement for appeasement.”

Over recent years, a stream of human rights victims testified in Parliament, each calling on the government to adopt the human rights legislation to demonstrate solidarity with activists and perhaps even protect them.

Some Canadian politicians, who use human rights advocacy as a primary justification for their political existence, rarely do little more than blow hot air without making any substantial difference.

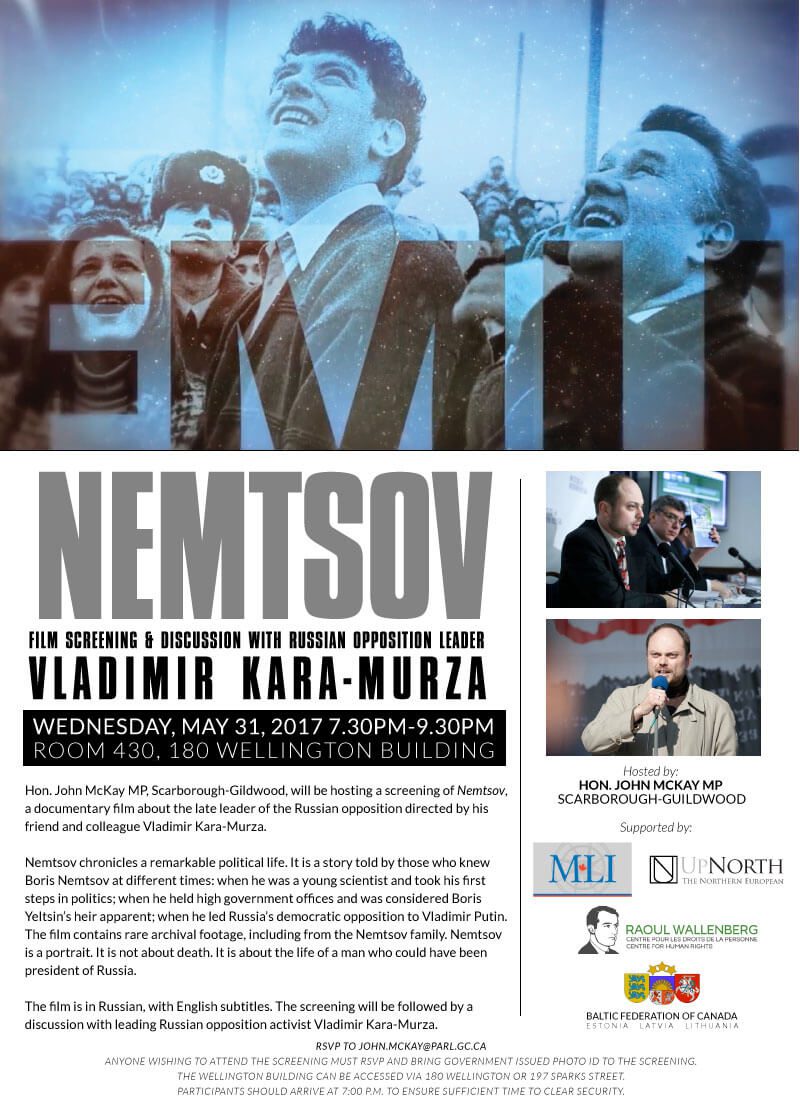

Among them was murdered Russian opposition leader, Boris Nemtsov, who asked parliamentarians to adopt Magnitsky legislation in 2012. Vladimir Kara-Murza, who between being poisoned the past two years, managed to come to Ottawa to echo Nemtsov’s requests. When Kara-Murza returns to Ottawa at the end of this month, it will hopefully be to thank parliamentarians for their solidarity and active support.

Some Canadian politicians, who use human rights advocacy as a primary justification for their political existence, rarely do little more than blow hot air without making any substantial difference. They know who they are. They avoid tough action on the worst human rights abusers — China, Iran, Russia — and save their torrents of principled fury for regimes in countries where Canada has few real interests, such as North Korea.

Magnitsky legislation will now enable Canadian parliamentarians to target abusers with pinpoint accuracy through a formal process that will eliminate superficial political risks and produce meaningful consequences for abusers that can alter bad behaviour.

In the long run Canada will embrace adopting Magnitsky legislation, just as it has with the Universal Declaration on Human Rights. Canada is a good and just nation, and today the world is looking to us for leadership. By adopting Magnitsky, we signal to them that we’re ready to for that challenge.

Marcus Kolga is a communications strategist, filmmaker and publisher of UpNorth.eu. He is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Foreign Policy Centre and is one of the leaders of the Canadian campaign for Magnitsky legislation.