This article originally appeared in the National Post.

By Shawn Whatley, February 6, 2023

People remain confused and uncertain about Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s three-step plan to expand health care services.We can correct confusion with facts.

Uncertainty, however, presents a bigger problem. Uncertainty lingers because many people do not understand profit or private enterprise itself.

Premier Ford said, “Ontarians will always access health care with their OHIP card, never their credit card.” The same message was shared last summer.

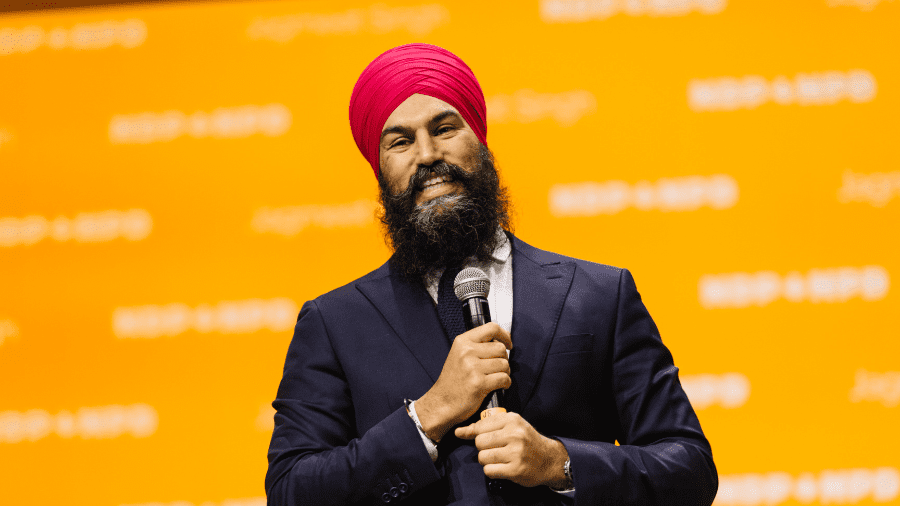

Nevertheless, Jagmeet Singh, leader of the federal NDP, tweeted, “We’re in the fight of our lifetimes. Conservatives who want American-style health care have begun privatizing health care.”

In another tweet, Mr. Singh said, “Let’s be clear, with private health care. You will get a bill.”

If he were honestly confused, Mr. Singh may have had reason. Headlines about “private care”, “for-profit” health care, and “private clinics” might make anyone wonder. Even Kathleen Wynne, former premier of Ontario, wrote, “We are seeing businesses whose sole purpose is to generate profit, putting themselves forward as the solution to all that ails us.”

Singh and Wynne speak to a deeper uncertainty beyond the facts — a sentiment shared by some Canadians: business cannot be trusted; profit is greed; private, for-profit care has no place in Canada. The sentiment leverages a distorted view of profit and private enterprise.

Canada spent an estimated $331 billion on health care in 2022. Every expense is someone else’s profit. Medicare is not a volunteer enterprise.

Although some pretend profit does not exist in Canadian care, medicare generates massive returns. Doctors, nurses, unions, medical associations, businesses, and banks create a complex web of salaries, medical fees, loan payments, service charges, rents, returns on investment, and much more.

Canada is not unique in this. Britain’s NHS offers universal, single-payer health care, with greater centralization and control than Canada. Roger Taylor, English author, a decade ago described similar challenges in the UK.

“The NHS has a fraught and complex relationship with the private sector … As one NHS manager put it, without business there would be no buildings, no drugs, no machinery, no beds, no scrubs — just a lot of doctors and nurses in a field in their underwear.”

In health care, people separate salary and investment returns into different moral categories. Salaries are good, investments are bad. We can pay a nurse to provide patient care, and even pay a contractor to construct a clinic. But we must not pay investors to finance the construction company — that would be immoral.

Canadian confusion about profit extends to private enterprise. We try to calm fears about private care by showing that most doctors currently own their own clinics. Many radiology suites and community laboratories are owned by physicians, also. Assorted therapists can own and run clinics offering publicly funded services.But none of this corrects the confusion about private enterprise itself.These private clinics are not true private enterprises. They are different than a retail store. A store owner can choose what to carry, set its price, and decide how much of it to sell. A store owner manages the store and decides whom to serve.Doctors’ offices, labs, radiology suites, or other clinics do not have these freedoms. The clinic owner maintains the privilege of owning the building or paying the lease, but the price, volume, types of services, and customers served are defined and controlled, in large part, by government.

Most people sense the difference between true private enterprise and a private medical practice, even if they cannot describe it. The alarmists tap this inability to articulate the differences to monger fear without explaining its source.Private delivery of publicly funded care was a pre-medicare dream. Once government assumed payment for care, it had to control costs, which meant finding ways to control care.Today, only an echo of private delivery remains. Hospitals are technically owned by private corporations, but they might as well be owned by government. Most clinics are technically owned by private clinicians, but each physicians’ contract increases government control.

Ludwig von Mises, twentieth century Austrian economist, described this shift in detail. In his classic text, Socialism: an economic and sociological analysis, he wrote, “The owner is left with nothing except the empty name of ownership, and property has passed into the hands of the State.”

Ford’s plan tries to slow this shift, maybe even reverse it slightly. If allowed to experience better care, patients may welcome more innovation. Until then, people such as Mr. Singh and Ms. Wynne will use public uncertainty to resist change: “We’re in the fight of our lifetimes.”

Shawn Whatley is a practising physician, senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and author of “When Politics Comes Before Patients: Why and How Canadian Medicare is Failing.”