In the new edition of Inside Policy, the magazine of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, Senior Fellow Benjamin Perrin explains why the Supreme Court of Canada deserved the title of “Policy-Maker of the Year” for 2014.

The article is based on Perrin’s recent report for MLI, which looked back at 10 of the most significant decisions the Supreme Court reached over the past year.

By Benjamin Perrin, Dec. 15, 2014

Each year, the Macdonald-Laurier Institute recognizes a “Policy Maker of the Year”. Past recipients have included former Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney and Minister of Foreign Affairs John Baird. One could argue that, while people in such positions are undoubtedly influential, there is another entity that is rarely acknowledged for its impact on policy yet in the last year has changed Canadian public policy in wide-reaching and long-lasting ways – the Supreme Court of Canada.

During the last year, the Supreme Court of Canada has made a series of landmark decisions in areas including Senate reform, Aboriginal title and treaty rights, prostitution laws, the appointment of justices to the Court from Quebec, security certificates, protection of CSIS human sources, undercover police operations, and sentencing. During this period, numerous commentators have characterized the decisions of the Court as reflecting a string of “losses” for Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government. Some have gone so far as to say that Canada has entered a “legal cold war” and that these “[l]egal conflicts reveal a clash of beliefs about how Canada should work”1.

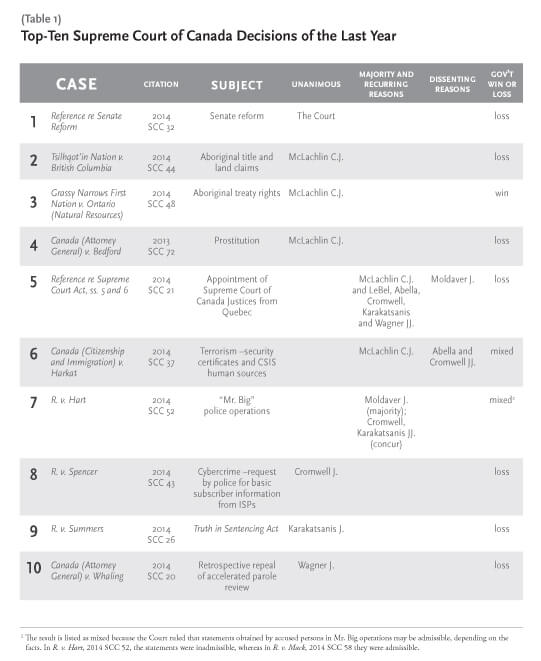

Within this context and while appreciating that the work of the Court is cyclical and outcomes vary from year to year, my recent MLI paper examines the Court’s ten most significant judgments of the last 12 months (November 1, 2013 to October 31, 2014) in terms of their importance and policy implications. Table 1 provides a snapshot of these decisions and their outcomes, while discussion and analysis of each is included in the full report, “The Supreme Court of Canada: Policy Maker of the Year”, available on MLI’s website.

Looking at these cases as a whole, this study made three findings.

1. The policy and legal impact of the Supreme Court of Canada’s decisions of the last year are significant and likely enduring.

In its decisions on significant constitutional matters in the last year, the Supreme Court of Canada has made bold decisions that fundamentally affect the way that Canadian democracy functions, the relationship between the Crown and First Nations (including with respect to resource development), limits on police investigative tactics, and decisions on controversial criminal law issues. It appears that the last year has likely had a disproportionate number of landmark cases of broad significance and interest to Canadians.

The most significant and enduring impact of the Supreme Court of Canada in the last year will be its interpretation of the amending procedures in the Constitution Act, 1982 in its reference decisions related to Senate reform and the appointment of judges to the high court from Quebec. Taken together, these decisions entrench the Senate and Supreme Court of Canada as institutions that are virtually untouchable. Changing the composition of either institution has been determined to require the approval of the House of Commons and the Senate as well as every provincial legislature.

The most significant and enduring impact of the Supreme Court of Canada in the last year will be its interpretation of the amending procedures in the Constitution Act, 1982 in its reference decisions related to Senate reform and the appointment of judges to the high court from Quebec. Taken together, these decisions entrench the Senate and Supreme Court of Canada as institutions that are virtually untouchable. Changing the composition of either institution has been determined to require the approval of the House of Commons and the Senate as well as every provincial legislature.

The Aboriginal law decisions of the Court in Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia and Grassy Narrows First Nation v. Ontario (Natural Resources) are landmark decisions which, together, demonstrate that the constitutional authority that the provinces have over resource development generally applies even in dealings with First Nations. In particular, “provinces may now clearly regulate and make decisions relating to natural resources, even when Aboriginal rights and title questions are involved.”3 However, provincial governments are obliged to respect Aboriginal title and treaty rights, as the case may be, in these interactions with First Nations. These recent authorities from the Court will undoubtedly be at the top-of-mind of provincial governments and private corporations that are seeking approval and implementation of large-scale natural resource projects now and in the decades to come.

Criminal law has always been a major part of the Court’s docket. The decision in Bedford is notable, not only on the issue of how prostitution may be addressed through the criminal law, but also because of the broader principles established in the decision with respect to the scope of section 7 of the Charter and its relationship with section 1 of the Charter. Bedford shifts the ground more broadly on when criminal laws will be found to infringe section 7, and creates a possibility of a successful section 1 justification argument by the government in appropriate cases. The next chapter of this saga will undoubtedly be a new Charter challenge to Bill C-36 (the legislative response to Bedford) that proponents of legalized/decriminalized prostitution have threatened.

The Court has upheld the availability of some national security and policing tools, including the security certificate regime and the Mr. Big technique, while imposing safeguards to ensure their constitutionality and appropriate use, respectively, but has ruled against others such as protecting the identity of CSIS human sources and the ability of the police to obtain basic subscriber information voluntarily from Internet Service Providers to address cybercrime (e.g. distributing child pornography).

The Court also made modest decisions related to recent sentencing law reforms introduced by Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government. The much more significant challenges to his criminal justice reforms have yet to be decided by the Court, in particular the constitutionality of a raft of new mandatory minimum penalties of imprisonment.

Table 1: Top ten Supreme Court of Canada decisions of the last year

2.The Supreme Court of Canada was a remarkably united institution with consensus decisions on these significant cases being the norm, and dissenting opinions rare.

The Court’s record on significant cases in the last year reveals a remarkably united institution, with unanimous decisions on most controversial cases that have come before it. Of the ten significant decisions reviewed, only two had dissenting reasons. In other words, in eight of the ten decisions, there was consensus on the outcome of the case (an 80% consensus rate). This rate of consensus stands out from recent years and is especially interesting given that it relates to the most significant decisions from the period under review.4

This study also found that Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin is showing leadership on major cases. Of these ten decisions, the Chief Justice was the sole-author of reasons in four of the ten cases and was a joint-author of two additional decisions. In all of these decisions, she was writing for either a unanimous Court or a majority of the judges. She did not dissent in a single significant case under review.

Due to the substantial unanimity of the Court’s major decisions, there is no evidence whatsoever of any deep fissures within the Court along ideological lines. This is in stark contrast to previous decades at the Court and what has often been the case at the U.S. Supreme Court. Related to this observation, there is no evidence whatsoever of any observable split in the Court’s decisions on significant issues between the six judges appointed by Prime Minister Harper and the three judges appointed by previous Prime Ministers during this period.

3. The federal government has an abysmal record of losses on significant cases in the last year, with a clear win in just one in ten of them.

Media commentary on the Court’s decisions raising the specter of a string of losses for the federal government at the Supreme Court of Canada was validated by this study. Of the ten significant decisions, the federal government won just a single case, while achieving mixed results in two cases. By way of providing some context, on average, 41% of Charter claimants have historically been successful in the Court – meaning that various levels of government succeeded in 59% of such cases on average.5

However, it bears mention that the abysmal record of recent losses for the federal government does not mean that all of these losses are attributable to legislation or recent action of the current federal government led by Prime Minister Harper. For example, some cases relate to government action originating decades ago, by other levels of government (e.g. in Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, the case was triggered by a commercial logging licence issued by B.C. in 1983 – nevertheless, the current federal government sided with B.C. and it lost).

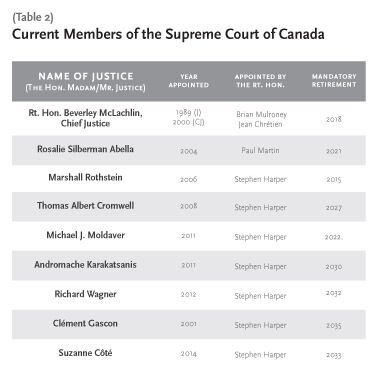

Table 2: Current members of the Supreme Court of Canada

Conclusion

The study found that during the last year, the Supreme Court of Canada has made landmark decisions having significant implications for law and policy across many areas. It has done so usually based on consensus, with just two cases among the top-ten most significant decisions having dissenting reasons. The Court has also ruled almost entirely against the federal government, with a single clear win among these most significant decisions.

One would be hard pressed to find another actor in Canada who has had a greater impact on such a wide range of issues than the Court has in the last year, such that the moniker “Policy Maker of the Year” is appropriate. The Court, no doubt, would resist such a label on the view that it simply applies the law. The Court has a constitutionally vital role both in interpreting and applying the law as well as providing constitutional scrutiny to laws and governmental action. However, as the study shows, it would be naïve and simplistic to say that the Court’s decisions do not have a significant legal and policy impact. Indeed, the outcomes and implications of the Court’s decisions of the last year are notable across a number of areas and will likely be of enduring significance for years – even decades – to come.

Benjamin Perrin is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia, Faculty of Law and a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. He previously served as Special Adviser, Legal Affairs & Policy in the Office of the Prime Minister and was a Law Clerk at the Supreme Court of Canada. Professor Perrin is a member of the Law Society of Upper Canada and Law Society of British Columbia. He is also the author/editor of several books, law review articles and book chapters, and regularly provides commentary in the media. Read his complete report “The Supreme Court of Canada: Policy Maker of the Year”.