The legacy of the George H.W. Bush’s administration is a carefully constructed international order that persists today, writes Richard Shimooka.

The legacy of the George H.W. Bush’s administration is a carefully constructed international order that persists today, writes Richard Shimooka.

By Richard Shimooka, December 10, 2018

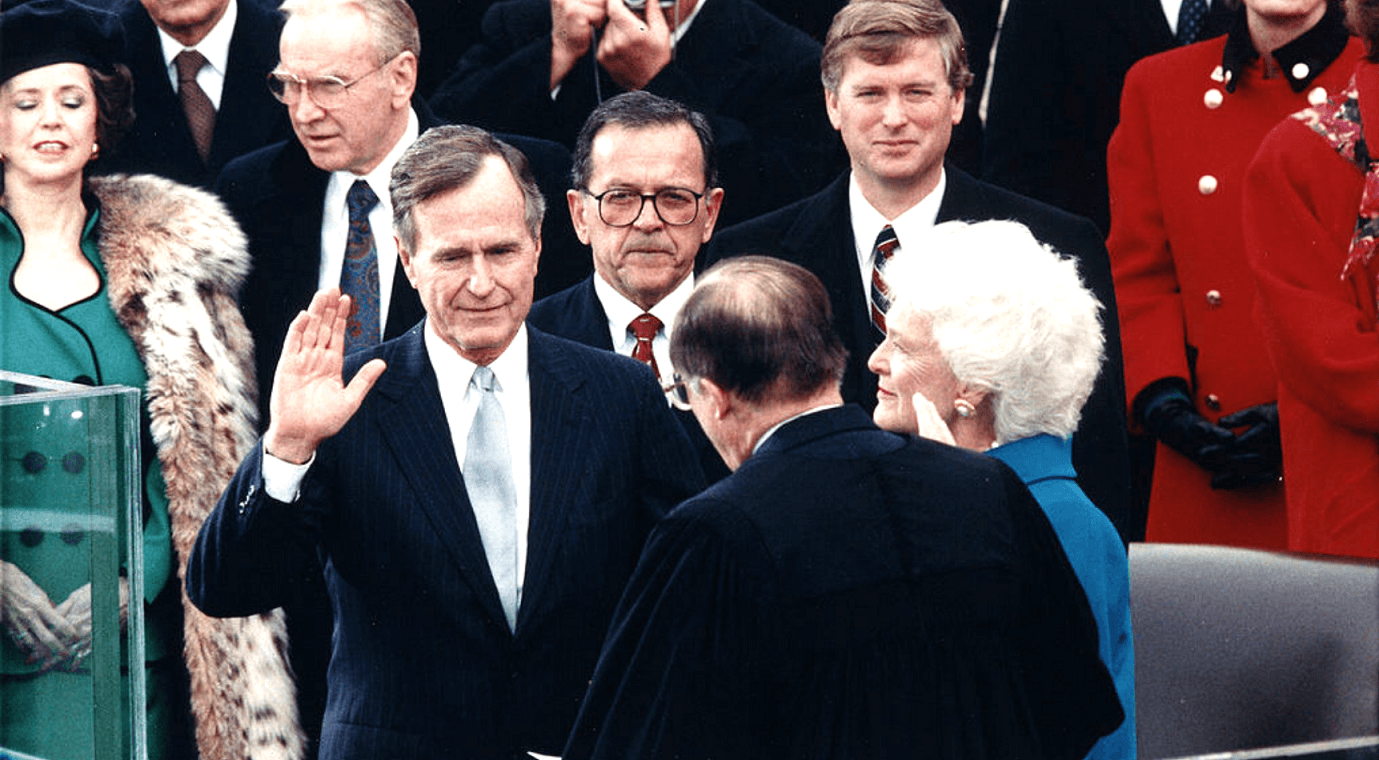

The passing of former president George H. W. Bush last week has been accompanied by the usual mix of lament for his temperament and prudent approach to governance, favourable comparisons with the current occupant of the White House, and concerns over questionable periods in his past.

Largely missed in these discussions on his legacy was the unique opportunity he had to fashion the international system that exists today. Bush’s presidency coincided with a critical inflexion point in history, where the arrangements of the international system were in-flux, and its future trajectory in doubt. Two are within our living memory. The first was Truman in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War with the emergence of the Soviet Union and the Cold War. His presidency created the Atlantic security institutions that would sustain the West for the Cold War. The Bush administration was the second, which guided the United States and the West during the twilight years and collapse of the Communist Eastern Bloc in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

It is hard to understate the challenges of that period. The withdrawal of Soviet forces from Eastern Europe and the collapse of client states left a massive political void worldwide. Problems immediately abounded. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait was the first, followed by Somalia, Yugoslavia and Afghanistan. Furthermore there were fears that a reunified Germany would reignite the flames of nationalism that been a destructive force in the first half of the twentieth century.

The Bush administration’s response was to create a series of conventions and institutions for managing international problems. This was first evident during Operation Desert Storm in Iraq; a multinational intervention designed to uphold the new international order. At the time, many within the U.S. were skeptical about the American military’s ability to win a major war after Vietnam. The resounding success would make it a model for the future use of force, though not without issues. Bush’s son and many of his former staff became victims of their own success, overestimating the U.S.’s ability to effect change with military force, which was evident during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

His experience as a World War II veteran led Bush to be more recalcitrant towards the use of military force, and wielded it carefully. This occurred during Somalia, where the U.S. launched a successful, limited operation that was narrowly focused on humanitarian objectives. It was only when the subsequent Clinton administration attempted a nation-building exercise that the effort became a fiasco, which was vividly captured in the film Blackhawk Down.

Perhaps as important as the tools was the security architecture that they were enmeshed within. As a former diplomat, Bush understood that that the United States required a strong diplomatic effort to achieve its aims. This included the support of close allies to legitimize the use of coercive power. As such, his administration refashioned the existing security architecture to manage future problems, the foremost being NATO, but to a lesser extent the UN as well.

None of this was preordained. NATO was viewed by some as a Cold War anachronism that would dissolve with the collapse of the Soviet Union. Many predicted the U.S. would retreat into isolationism. Instead, the administration’s careful diplomacy ensured that NATO was transformed into an organization able to deal with international security challenges broadly. It also provided careful encouragement that helped create the European Union, which would provide a moderating role within the continent and calm fears of a newly reunified Germany. Bush also undertook a strong diplomatic outreach to adversaries, which was instrumental in placating Soviet authorities during the collapse of their existing order.

The post-Cold War order they helped to create remains largely intact today, though it faces strains. The legacy of the USSR’s collapse still confounds us, such as the confrontation around the Sea of Azov between Russia a Ukraine last week. Ironically, the Bush administration was concerned about the reemergence of a hostile Russia, and the security architecture they put into place has coped adequately to these challenges.

The legacy of the George H.W. Bush’s administration is a carefully constructed international order that persists today. Current policy-makers should take close heed for present challenges. While the Bush administration did not design an effective security response to China, the same lessons can be applied. Effective diplomacy, both with building an effective security regime with allies, and in managing Beijing’s expectations are critical for future success. Needless antagonism, such as that surrounding tariffs or coercing or abusing allies, will only be counterproductive to U.S. interests in the end. Understanding these enduring lessons, and reapplying them today may be the best tribute one can offer to the late president.

Richard Shimooka is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s Centre for Advancing Canada’s Interests Abroad.