The Canadian government’s commitment to the rule of law will serve us well through the political storm, writes Scott Newark for Inside Policy.

The Canadian government’s commitment to the rule of law will serve us well through the political storm, writes Scott Newark for Inside Policy.

By Scott Newark, December 21, 2018

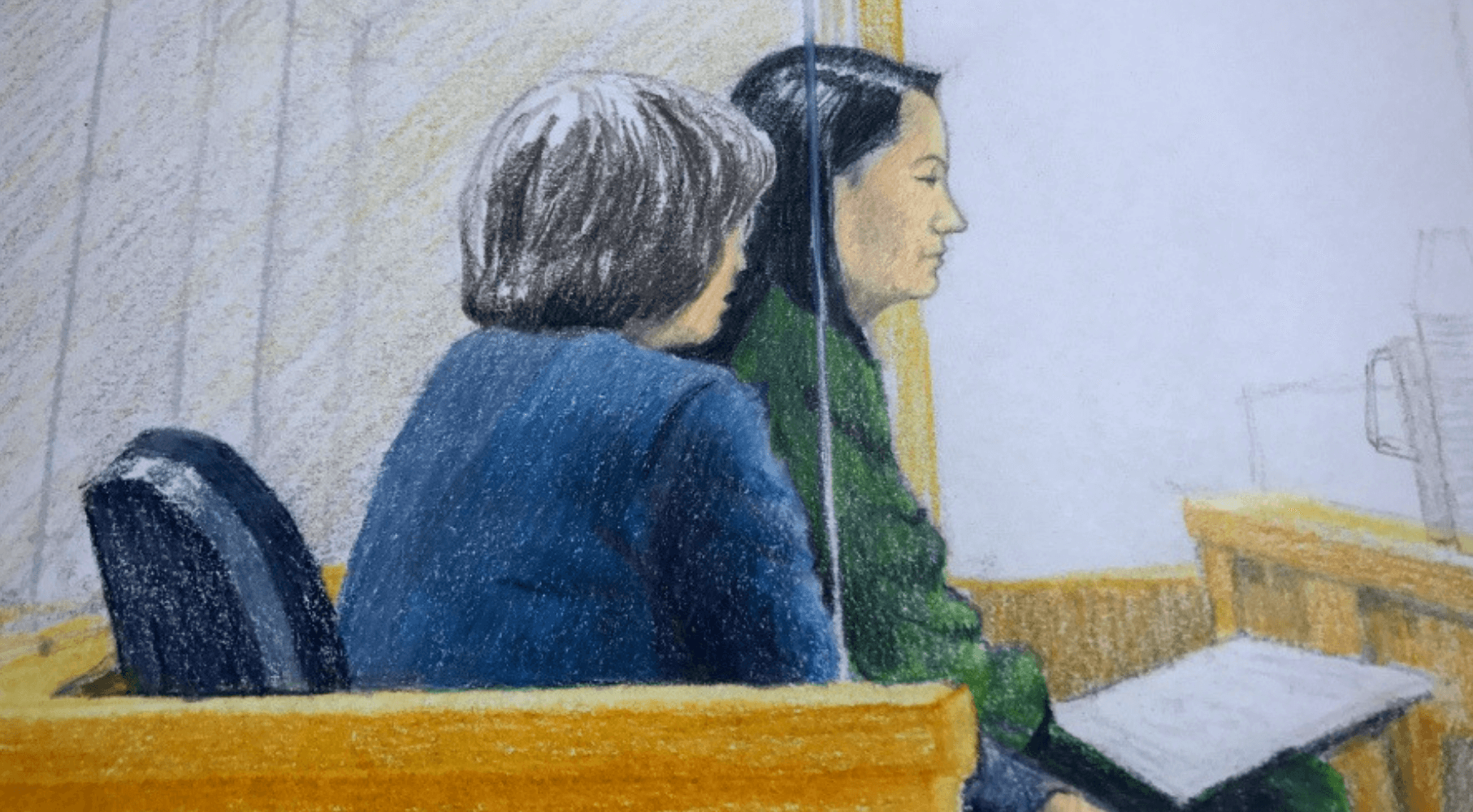

On Saturday December 1, Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou was arrested and detained by Canada Border Services Agency officers at the Vancouver International Airport after she deplaned from a Cathay Pacific flight from Hong Kong.

Meng was intending to board a connecting flight to Mexico but was instead taken into custody pursuant to a provisional court ordered arrest warrant issued by a Canadian judge pursuant to Canada’s Extradition Act. The arrest warrant was issued after Canadian authorities received a formal request from US authorities under the Canada-US Extradition Treaty which, if the qualifying conditions are met, Canada is obliged to act on.

Meng’s arrest resulted in an explosion of media attention because her firm Huawei is a China-based telecommunication company that is one of the world’s largest and which is the cause of security concerns for multiple countries as it is rightly seen as an agent of the Chinese state. Three members of the “Five Eyes” Intelligence group, the US, New Zealand and Australia, have announced a ban on Huawei being involved in the upcoming 5G telecoms modernization in their countries, which the UK is also moving to. Meanwhile, only Canada remains “undecided” despite the near universal warning from current and former security officials that Canada should also ban Huawei from 5G projects going forward.

The sensitivity of Meng’s arrest is heightened by the fact that she is also the daughter of the company’s founder and President, Ren Zhengfei, a former Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) officer. Meng and her father are part of autocratic China’s elite and her arrest by Canada is seen by them as nothing less than an insult to China itself.

Adding to the perception of something more than a regular criminal extradition being involved was that the arrest literally took place on the very day that US President Trump and Chinese President XI Jinping met at the G20 Summit and announced a 90-day effort to resolve trade and tariff disputes. Trump’s office has since denied knowing about the US extradition arrest request while Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says he was aware but never spoke about it with his US or Chinese counterparts at the Summit.

The details of the charges against Meng Wanzhou were vague at first but subsequent reporting and evidence at her bail hearing have revealed that the US charges are multiple counts of conspiracy to defraud different financial institutions, including HSBC, by providing them false information about a Huawei controlled telecommunications firm, Skycom, which they used to conduct business in Iran which was illegal as it was a contravention of US sanctions against that country. HSBC officials allege they received a misleading briefing on this issue from Meng Wanzhou on behalf of Huawei in 2013 and in 2016 they reported their concerns to US federal prosecutors who opened a formal investigation into the matter which Huawei was aware of by April 2017. The warrant for Meng’s arrest on this matter was issued by a court in New York on Aug. 22 of this year.

US authorities somehow became aware of her travel plans days before her arrival in Canada on Dec. 1 and notwithstanding the fact that the US has an extradition treaty with Mexico, they made the arrest request to Canada in accordance with the Canada-US Extradition Treaty which dates back to 1971. As first noted by Macdonald-Laurier Institute Managing Director Brian Lee Crowley, Canada’s arrest and court proceedings against Meng Wanzhou are based on our legal obligations which now and in the future ensure that our actions will be conducted in accordance with our commitment to the rule of law.

While this concept may baffle the Chinese autocracy, and Donald Trump, it defines how we have acted to date and will act in the future. To her great credit, Canadian Global Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland has effectively and unequivocally championed and articulated this core principle of Canadian society.

As more details of the US allegations have emerged, questions are increasingly being asked about why US authorities are pursuing charges against Meng Wanzhou personally rather than laying corporate charges against Huawei the company on whose behalf she was acting. This corporate prosecution approach was used by the US recently against ZTE Corporation, another Chinese telecom giant, after it too was found to have violated US sanctions against Iran and North Korea. ZTE was forced to pay $1.9B in penalties and an imposed seven-year ban against the company operating in the US was lifted earlier this year after Chinese President XI intervened with President Trump.

Given Canada’s insistence of our actions being governed by the rule of law, this question will be at the core of whether Meng is extradited to the US. Canada’s Extradition Act and our specific treaty with the US are clear that pre-conditions for extradition are an alleged offence against a person, not a corporation, and that the offence alleged is also an offence in Canada had the actions occurred in Canada (s. 3(1)(b) Extradition Act). The Canada-US Treaty lists 30 different offence types and potentially items 12 and 15 relating to fraud will be cited with s. 380 of the Canadian Criminal Code being the “equivalent” offence as it states:

380 (1) Every one who, by deceit, falsehood or other fraudulent means, whether or not it is a false pretence within the meaning of this Act, defrauds the public or any person, whether ascertained or not, of any property, money or valuable security or any service …

Meng Wanzhou is alleged to have been the person who deceitfully misled US banks about how her company was doing business to avoid the Iran sanctions and thereby increase profits although she clearly did so on behalf of Huawei and it was the company and not her personally that received the bank services and thus the direct financial gain. Expect her lawyers to make this argument at all stages in the extradition process.

In addition to that, Minister Freeland may also wish to point this out in blunt terms to her US counterparts because if the US decides that on further consideration this is best pursued as a “corporate prosecution”, that means the extradition request against Meng Wanzhou would be withdrawn and Canada would end the case and allow her to return to China. Given Minister Freeland’s recent trip to meet US Secretary of State Pompeo and her subsequent remarks, that effort may already be underway.

If this does not happen anytime soon, it is also important to understand what exactly following the Canadian “rule of law” will mean for this case and how it will likely unfold. First, as noted, Canada was legally obliged to arrest and detain Meng and to start the extradition court process which is now underway including her being granted bail. Under the Extradition Act the requesting country (US) now has a set time period (end of January) in which it must provide the Minister of Justice with a summary of the evidence it intends to call to demonstrate the extradition is justified in law. Following the receipt of the evidentiary summary, the Minister has an additional 30 days to decide, based on the defined criteria and exceptions, whether an “Authorization to Proceed” should be issued.

Should that Authorization be given, which it almost always is, the case will go back to Superior Court in BC and the presiding Justice will review the evidentiary summary as well as submissions from counsel and then decide if the extradition criteria have been satisfied. If an extradition order is made, the case goes back to the Minister who has a residual discretion to decide whether to order that the extradition take place. The order of the Court to extradite and the Minister’s approval of extradition are subject to appeal at the BC Court of Appeal and even potentially in the Supreme Court of Canada. Put differently, this could take a very long time to resolve which, given the political aspects of this case with both the US and China, is probably not viewed favourably by the Canadian government.

Not surprisingly, it is the “political” aspects of this extradition case that have generated so much public attention. Because the arrest and detention were carried out by Canada, Canada quickly became the target of attack by China with their Ambassador to Canada describing the arrest as a “miscarriage of justice,” and a pre-meditated US “political action”.

That allegation gained credibility when mere days after the arrest US President Trump narcissistically chimed in by saying, “If I think it’s good for the country, if I think it’s good for what will be certainly the largest trade deal ever made — which is a very important thing — what’s good for national security — I would certainly intervene if I thought it was necessary.”

This politicization of the case has also resulted in China arresting and detaining two Canadians working in China on supposed “national security” grounds and a third arrest of a Canadian teacher which also is a signal of China’s autocratic and bullying response. These arrests create further difficulties for the Canadian government as it attempts to live up to its rule of law principles while dealing with a country that has blatant disregard and disdain for that system of governance, which we take for granted.

Another potential consequence of the politicization of the case is that it may well trigger mandatory statutory exceptions under the Extradition Act which the Minister is obliged to consider. Section 44(1)(b) of the Act prevents extradition if the Minister is “satisfied” that:

(b) the request for extradition is made for the purpose of prosecuting or punishing the person by reason of their race, religion, nationality, ethnic origin, language, colour, political opinion, sex, sexual orientation, age, mental or physical disability or status or that the person’s position may be prejudiced for any of those reasons.

Section 46(1)(c) of the Act also compels the Minister to refuse extradition if she is satisfied that:

(c) the conduct in respect of which extradition is sought is a political offence or an offence of a political character.

In light of the burgeoning trade war between the US and China and President Trump’s clear remarks that he views the case as a bargaining chip, which he will exploit, Meng Wanzhou’s lawyers clearly have an argument to put forward. Canada’s commitment to the rule of law works both ways, which is a message that Minister Freeland emphasized while in Washington after President Trump’s remarks when she said:

“Canada understands that the rule of law and extradition issues ought not to ever be politicized or used as tools to resolve other issues. … That is the very clear position which Canada expresses to all of its partners.” (Global News-December 14, 2018)

In light of all of this, it is entirely possible that “diplomatic” discussions are underway to find an acceptable solution for all three countries. That solution could include the following actions:

- The US will reconsider its extradition request and conclude that a corporate prosecution is more appropriate than one against Meng Wanzhou personally;

- Canada and US will confirm with China that if Wanzhou is released the three Canadians being held will be released and removed to Canada;

- The US will withdraw its extradition request which Canada will comply with and release her from current bail restrictions and return her and her family to China (where we will pick up the three Canadians)

Once that is accomplished, Canada will quietly (late on a Friday) thereafter, without advance notice to China, announce that it is joining US, NZ, Australia and (probably) UK in banning Huawei from upcoming 5G projects, which Donald Trump will claim as another personal victory.

The Meng Wanzhou extradition case has understandably attracted significant public attention in all three countries. Whether it is resolved through diplomatic deal making or through the court and ministerial approval process, that scrutiny will continue. As awkward as it has been for Canada to be caught in the middle of this US-China dispute, our commitment to following our rule of law is the right way to proceed. Stay tuned.

Scott Newark is a former Alberta Crown Prosecutor who has also served as Executive Officer of the Canadian Police Association, Vice Chair of the Ontario Office for Victims of Crime, Director of Operations for Investigative Project on Terrorism and as a Security Policy Advisor to the governments of Ontario and Canada. He is currently an Adjunct Professor in the TRSS Program in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University.