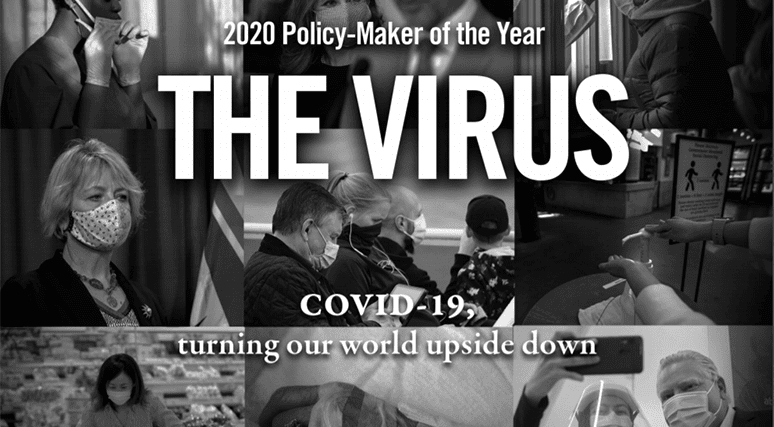

Canadians are eager to put the pandemic behind them. The sad news though is that there is reason to believe that the carnage COVID-19 has unleashed will continue to rock Canadian society for years to come. COVID-19 had undeniably been the policy-maker of 2020, and Anthony Furey asks: will our politicians allow it to dominate the coming year as well?

Canadians are eager to put the pandemic behind them. The sad news though is that there is reason to believe that the carnage COVID-19 has unleashed will continue to rock Canadian society for years to come. COVID-19 had undeniably been the policy-maker of 2020, and Anthony Furey asks: will our politicians allow it to dominate the coming year as well?

This article is the feature story for MLI’s Policy-Maker of the Year issue of Inside Policy. The full issue can be read here.

By Anthony Furey, December 21, 2020

It’s hard to give a firm answer to the question of when COVID-19 actually hit Canada. Technically speaking, the first positive case of the virus was confirmed on home soil on January 27, in the Greater Toronto Area. But it didn’t sink in for everyone at that time.

There were those who had been watching as a mysterious illness started spreading like wildfire through the Hubei province of China. This region was plunged into a lockdown that at the time was unprecedented in modern human history. To some it seemed like something far away, something that would never happen to us. But for those Canadians watching the situation in China closely, the Hubei lockdown was likely when the hairs started to stand up on the backs of their necks.

While the occasional case cropped up in Canada, the month of February was one of relative calm. Health officials and politicians reassured the public with the mantra that they’d learned their lessons when SARS touched down in Canada, killing 44 Canadians, more than 15 years prior.

What can be firmly said is that at some point during this early period, policy-making in Canada underwent a seismic shift. Almost every decision made by policy-makers in Canada – ranging from small-town councillors to the Prime Minister – would from then on be made with the emerging Wuhan virus, later labelled SARS-COV-2, in mind. COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, became the fixed point around which all other objectives manoeuvred.

The month of February can now be looked back on as the time before the fall, when a complacent nation told itself that the virus that had spread from China to then ravage Iran and Italy would never find its way up to the great white north.

Until it did.

The federal government was at first reluctant to close the borders and ban incoming flights. They were even resistant to quarantining a full plane of repatriated Canadians from Wuhan at a time when it was still the epicentre of the outbreak.

Some officials even said that the threat of racism and discrimination against those wrongly perceived to be carrying the virus would, when all was said and done, end up being a greater scourge for Canada than the virus itself.

The month of February can now be looked back on as the time before the fall, when a complacent nation told itself that the virus that had spread from China to then ravage Iran and Italy would never find its way up to the great white north.

Until it did.

For many Canadians, the second week of March was when it really hit them. A number of notable things happened that week to shock people out of their complacency.

Canada recorded its first COVID-19 death. Popular movie star Tom Hanks announced he and his spouse were tested positive for the virus, the first such news from a well-known celebrity. The NBA announced the suspension of their season, meaning Toronto’s beloved Raptors would have to pause their attempt at a repeat performance as champions. And, in the move that had the greatest impact on people’s lives, Ontario schools were shutting down for the two weeks following March break.

That two weeks of school closures then turned into four months. The closure of just a few establishments soon became the shut down of everything but the essentials. People who could work from home did. Those who couldn’t either braved it and went out as essential workers or they stayed home, without employment and with loss of income.

For a very brief period, it looked like a whole segment of society would soon be without a way to put a roof over their heads and food on the table. Then Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the beginning of a whole range of alphabet soup programs to prop up workers and businesses shut down by what was now obviously a global pandemic. This was when the virus really took total charge of government decision-making.

There was soon something on offer for everyone. Philip Cross, an MLI senior fellow, has noted that our generous helpings may turn around to bite us. “Household disposable income in Canada rose the most of any major nation, as government transfers more than replaced the loss of earned income during the lockdown and most of this money was saved rather than spent,” he notes in an MLI commentary. “As a result, government deficits in Canada were the largest in the G20 and nearly twice as large as in Europe.”

That the government was at first late to the party on decisive actions was in part caused by the initial reluctance of the World Health Organization to call for drastic measures, decisions that were believed to be influenced by political pressure from the Chinese Communist Party. Then it was too late to prevent the rampant spread of the disease.

Canadians sheltered in place, as the saying went, as they watched the full eruption of what became known as the first wave. While the worst of it appeared to be playing out in atrocious scenes coming from unprepared long-term care facilities, there was also the very real fear that anyone could have caught it from anyone, and that anybody could die from it.

Previously unknown public health officials became the new “ministers of everything,” appearing as key voices at government press conferences.

Previously unknown public health officials became the new “ministers of everything,” appearing as key voices at government press conferences. Politicians claimed to be mere servants of “science” and “evidence,” while the evidence changed daily and much was suspect.

Their most basic recommendations were clear from the start: Wash your hands; cover your mouth when you cough; stay home if you feel sick. Those soon evolved to include staying six feet apart and, much later, to wearing a mask when indoors.

People took their own added precautions. Particularly at the beginning. They wiped down their packages. They opened their mailboxes and door handles with their sleeves or wipes. Some people avoided the shops entirely.

By this time, society had come to a near standstill. The border was closed. Rush hour in major cities was non-existent. Even hospitals had stopped admitting patients for anything other than urgent life-saving procedures.

Not everyone was sold on this approach though. Expert voices were already stepping forward to urge a more balanced approach.

“We need to be thinking about risk trade-offs: we can prevent the spread of the virus in any workplace by shutting that workplace down completely, but that will also force its output zero,” wrote Brian Ferguson, an economics professor at the University of Guelph, in a prescient MLI commentary from April.

But Ferguson noted that workplaces deemed essential were devising protocols that let them continue operations. “We should extend that thinking to other places. If a non-essential workplace turns out to be low risk for transmission, why should it stay closed?”

It became clear by then that both our daily lives and our approach to public policy had profoundly changed because of the virus, and would remain so for quite some time.

Heartbreaking images surfaced of fatigued health care workers and of seniors who could only see loved ones through glass. People put up posters outside of their homes thanking essential workers and healthcare heroes.

Heartbreaking images surfaced of fatigued health care workers and of seniors who could only see loved ones through glass. People put up posters outside of their homes thanking essential workers and healthcare heroes.

Then, as that awful phrase “the new normal” became a reality, we were finally able to slow down and grab our bearings. We took a deep breath and a more robust conversation started.

Health policy in particular was brought under a lens for national focus. We talked about testing, contact tracing and vaccines. As predictions of a second wave increased, so did recommendations to do more to protect our elderly and the most vulnerable.

But keen observers noticed that this conversation also involved policy-makers “shifting the goalposts,” as an open letter put together by the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and co-signed by prominent Canadian thought leaders explained it.

“The rationale for the lockdown seems to have morphed subtly from managing the outbreak by ‘flattening the curve’ to preventing the illness from infecting Canadians at all, pushing the timeline for a return to some economic activity into the summer and a return to ‘normal’ a year or more into the distance when a vaccine is available,” the letter noted. “It’s an impossible goal that is being pursued at an almost incalculably large cost to the wellbeing of Canadians in exchange for a largely illusory benefit.”

Others followed MLI’s lead, as groups of infectious disease and health policy experts broke away from the groupthink that had dominated in the early going of the lockdown.

But then came a reprieve with the summer lull in the number of COVID-19 positive cases and deaths. Was the pandemic over? Life itself began to resume. And all with relative safety. There were those who wrung their hands at the sight of people gathering in parks and on beaches. We soon learned that there was nothing to fear about such gatherings. It’s true that there were no rock concerts or ball games, and most white-collar workers still stayed home from the office, but other than that, things looked familiar again.

While parents were facing July and August deadlines about whether to send their kids back to school or not – while most did, a sizeable minority did not – for the most part COVID-19 was out of sight, out of mind during the summer. For fatigued voters enjoying the post-lockdown sunshine, demanding that politicians and public health officials do more to prepare for a second wave was the last thing they wanted to focus on.

“We benefited from the subsequent reduced incidence of COVID-19 in the late spring through summer,” note Hugh O’Reilly, Matthew Bourkas and James K. Stewart in a November MLI commentary. Did we use that time productively? “Unfortunately, governments did not use this period to sufficiently bolster their testing and tracing capabilities and to invest significantly more in advancing treatments and communications.”

And now the second wave is upon many countries, including Canada. Those omnipresent graphs show an almost flatline of low numbers throughout all of June, July and August and then, as if on cue, the line begins to climb after Labour Day and is climbing still, especially in hard-hit Ontario and Quebec. By the end of September, the daily case counts began to exceed what they were during the first wave. But so far, the tragic deaths are nowhere near those counted during the spring.

Several provinces and municipalities have now enacted the tightest restrictions since the spring, including a ban on even outdoor patio dining, and products on store shelves in some jurisdictions are now roped off, unavailable for consumers to purchase. There are those who applaud these measures and then there are those – including major businesses associations – who ask if the evidence actually backs up such decisions.

The medical community is now split on what to do. There are those who call for the COVID Zero approach, where the most severe of restrictions is justified in the name of getting Canada to zero new daily COVID-19 cases.

Then there are those doctors who say the cost isn’t worth it, that there will be too much economic ruin, suicide, delayed surgeries, damage to kids’ development and more. They urge us to open up more.

These same doctors point out that the situation is much better than everyone first thought it would be. The second wave is not the first wave. Much has been learned about COVID-19.

Doctors know how to treat the virus in terms of when hospitalized patients need ventilators and which drugs to appropriately administer. The data confirms that the overwhelming majority of people who have a serious outcome are the elderly with multiple underlying health conditions who live in group settings. School children, for example, have not proven to be super-spreaders as first feared. Kids are not getting the illness in significant numbers and when they do it’s rarely serious.

This good news hasn’t filtered down to everyone and policy-makers seem resistant to pivot towards an approach that would empower Canadians to learn to live responsibly with COVID-19.

The saying in the spring was “we’re all in this together.” Few people balked at the restrictions. Politicians from opposing sides of the spectrum were glad to link arms. Now, that’s all gone. The centre hasn’t held and things have fallen apart.

The saying in the spring was “we’re all in this together.” Few people balked at the restrictions. Politicians from opposing sides of the spectrum were glad to link arms. Now, that’s all gone. The centre hasn’t held and things have fallen apart.

The number of protests in the streets against lockdowns are rising. Some people hold firm to COVID-19 conspiracy theories, while others relish what they see as a great opportunity to enact a socialist “reset” of the economy.

Business owners are defying the restrictions, risking fines and even arrest. Politicians have resorted to their usual tricks, blaming each other and trying to score political points off of their opponents.

What happens next? Politicians seem to be crossing their fingers and awaiting a vaccine, content to continue opening and closing businesses in a seemingly arbitrary fashion. Meanwhile, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has presented a fall economic statement that appears more focused on using the pandemic as a tool to implement a reset towards a “green transformation” than returning Canadians to the way they lived before.

What politicians do not seem willing to acknowledge is that even with a vaccine, we may have an endemic virus on our hands that continues to ebb and flow in the background as we slowly come to terms with such a depressing reality and learn to live with COVID-19.

Meanwhile, policy-makers will have to grapple with the broader long-term implications — social, financial, political and more.

“The aftermath of COVID-19 will invariably produce a new geo-strategic environment,” MLI senior fellow Richard Shimooka writes in an MLI policy paper. Canada needs to be prepared, he notes, and “failing to do so could magnify the pandemic’s consequences from a public health and economic crisis to a collapse of the Western position within the international system.”

Canadians are eager to put the pandemic behind them. The sad news though is that there is reason to believe that the carnage COVID-19 has unleashed will continue to rock Canadian society for years to come. COVID-19 had undeniably been the policy-maker of 2020. Will our politicians allow it to dominate the coming year as well?

Anthony Furey is a columnist and opinion editor for the Sun chain of newspapers.