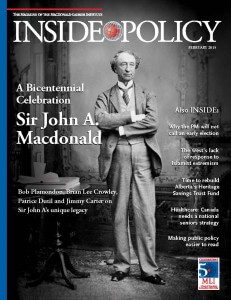

In the Feb. 2015 edition of Inside Policy, the magazine of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute,  Canadian Medical Association President Dr. Chris Simpson says it’s time to get seniors out of expensive and overcrowded hospital beds.

Canadian Medical Association President Dr. Chris Simpson says it’s time to get seniors out of expensive and overcrowded hospital beds.

Instead, he says, the federal and provincial governments should work together on a strategy for placing as many seniors as possible into long-term care or back into their homes.

By Christopher Simpson, Feb. 13, 2015

The urgent need for a national seniors strategy involving all levels of government, including Ottawa, can be nicely summed up with two words — “Code Gridlock.”

I hear these two words far too often at Kingston General Hospital where I am on staff.

Code Gridlock is every bit as ominous as it sounds. When a hospital exceeds its capacity, these two words go out on pagers and smart phones to physicians, administrators, nurses and support staff in hospitals all over Canada, or over the PA system as is the case at my hospital.

It means the hospital is so full that patients can’t move. Patients in emergency can’t go upstairs to beds because they are full. Sometimes ambulances can’t offload patients into ER because it is packed – even in the hallways. Elective surgeries are cancelled. Transfers from the region are put on hold. Patient flow, has ground to a halt.

To those outside the medical world, the two words probably won’t be heard over the white noise of a busy hospital. But to everybody else in the building they work like a dog whistle — start freeing up beds immediately. My hospital has been in Code Gridlock for the past three months.

The home care folks go into overdrive to try to get already–stretched services into place for patients nearing discharge. The social workers call in favours to try to get long–term care facilities to squeeze in one or two more people.

All hospitals in the region are told that we can’t take any patients other than “life and limb” problems. All physicians, nurses and other health care professionals are urged to do whatever they can to expedite discharges.

Every manager, director, chief of staff and VP must focus on patient movement. That means unclogging the system one patient at a time.

Despite our efficiencies that compare favourably to best in class – including length of stay and other measures that help to define optimal capacity – despite judiciously balancing our shrinking budget – despite getting as lean and efficient as I think we can possibly get – we are increasingly in gridlock.

Code Gridlock was developed to deal with the inevitable surges in hospital activity – a way to squeeze extraordinary performance out of the system. But increasingly, Gridlock is becoming the norm.

Kingston General is far from alone. Victoria Hospital in London, Ont., was at 125 per cent capacity on the weekend following this past Christmas.

On January 19, the Ottawa Hospital was at 110 per cent of capacity with 51 patients in emergency waiting for beds.

Thunder Bay Regional Health Centre was hit with a fire department citation because it was reduced to squeezing patient beds into hallway alcoves.

Alberta recently decided to spend $180 million to get 700 seniors out of its overcrowded hospitals.

So what does Code Gridlock have to do with a national seniors strategy involving all levels of government with Ottawa taking the lead?

In the hospital world we have another code – ALC. It stands for alternate level care as opposed to acute care. They are almost always seniors.

These are patients who no longer require acute care and for all intents and purposes are able to leave the hospital. More to the point, they should be leaving the hospital not only because the beds are needed by others but because the hospital is, ironically, a dangerous environment for patients who have chronic but not acute disease.

Hospitals are not set up to look after people with chronic diseases. Patients get deconditioned, they fall, and they suffer hospital–acquired infections. They don’t get the care they need and deserve.

ALC patients are trapped. We are warehousing them. We do the best we can. But it’s not anywhere near good enough. It is, frankly, disgraceful.

Fifteen per cent of acute–care hospital beds in Canada are occupied by ALC patients. The CMA estimates $2.3 billion a year that could be used elsewhere in the health system if we could just break the habit of warehousing our seniors in hospitals.

Let’s do some math. It costs $1,000 to keep a person in a hospital bed for a day. Long–term care costs $130 a day. Home care $55. The CMA believes about $2.3 billion a year could be better spent in the health care system with some strategic thinking and investing.

If anything, it is the fault of our hospital–centric system for quietly conducting an internal debate among ourselves using obscure lexicon like ALC when we should have let our patients in on this dirty little secret. It’s our fault for devising workarounds to keep a broken system afloat – complicit in the knowledge that doctors and nurses and others, in sincere efforts to do their very best for patients, too often accomplish excellence despite the system rather than because of it.

Our system has been neglected. Our health care professionals have kept it afloat.

Policy makers need to wear a big chunk of this problem. Our health care system was set up 50 years ago when the average age of a Canadian was 27. The health care landscape was one of acute disease. So we built hospitals. And we made the health care system about hospitals and doctors.

Today the average age is 47. And the landscape is now one of chronic disease – like diabetes, dementia, chronic obstructive lung disease, heart failure and arthritis.

Yet the system hasn’t changed much.

So I am not talking about throwing a lot of money to update the health care system. That’s not practical. We need to spend smarter.

We need a national seniors strategy involving all levels of government, and with Ottawa taking a leadership role. We see this as a much more positive alternative to quarreling over who is in charge of what and who should pay.

As an intermediate measure we need to step up investment as a society in long–term care. We must also develop and invest in a plan that recognizes people want much more support and services that will help them stay in their homes and communities.

The need to dehospitalize the system and deal with Canada’s aging population should be priorities in a national seniors strategy. This is why the Canadian Medical Association, the Canadian Nurses Association and others are working to make the need for a national seniors strategy a ballot issue in this year’s federal election.

Canadians over 65 currently account for half of all health costs. By 2031 seniors will present 21 percent of the populations and 59 percent of the health costs. We no longer have the luxury of time.

We can save our health care system if our governments are prepared to sit down and develop a national strategy dedicated to the principle of aging well and quality care for all.

Fifty years ago Tommy Douglas showed us a better way. Fixing seniors care will go a long way in renewing the entire health system.

Dr. Chris Simpson is Professor of Medicine and Chief of Cardiology at Queen’s University as well as the Medical Director of the Cardiac Program at Kingston General Hospital / Hotel Dieu Hospital. He became president of the Canadian Medical Association in August 2014. He serves as the Chair of the Wait Time Alliance and as Chair of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society’s Standing Committee on Health Policy and Advocacy.