MLI Managing Director Brian Lee Crowley writes that a worrying question must be asked: is Canada a society governed by the rule of law or not?

MLI Managing Director Brian Lee Crowley writes that a worrying question must be asked: is Canada a society governed by the rule of law or not?

By Brian Lee Crowley, February 12, 2019

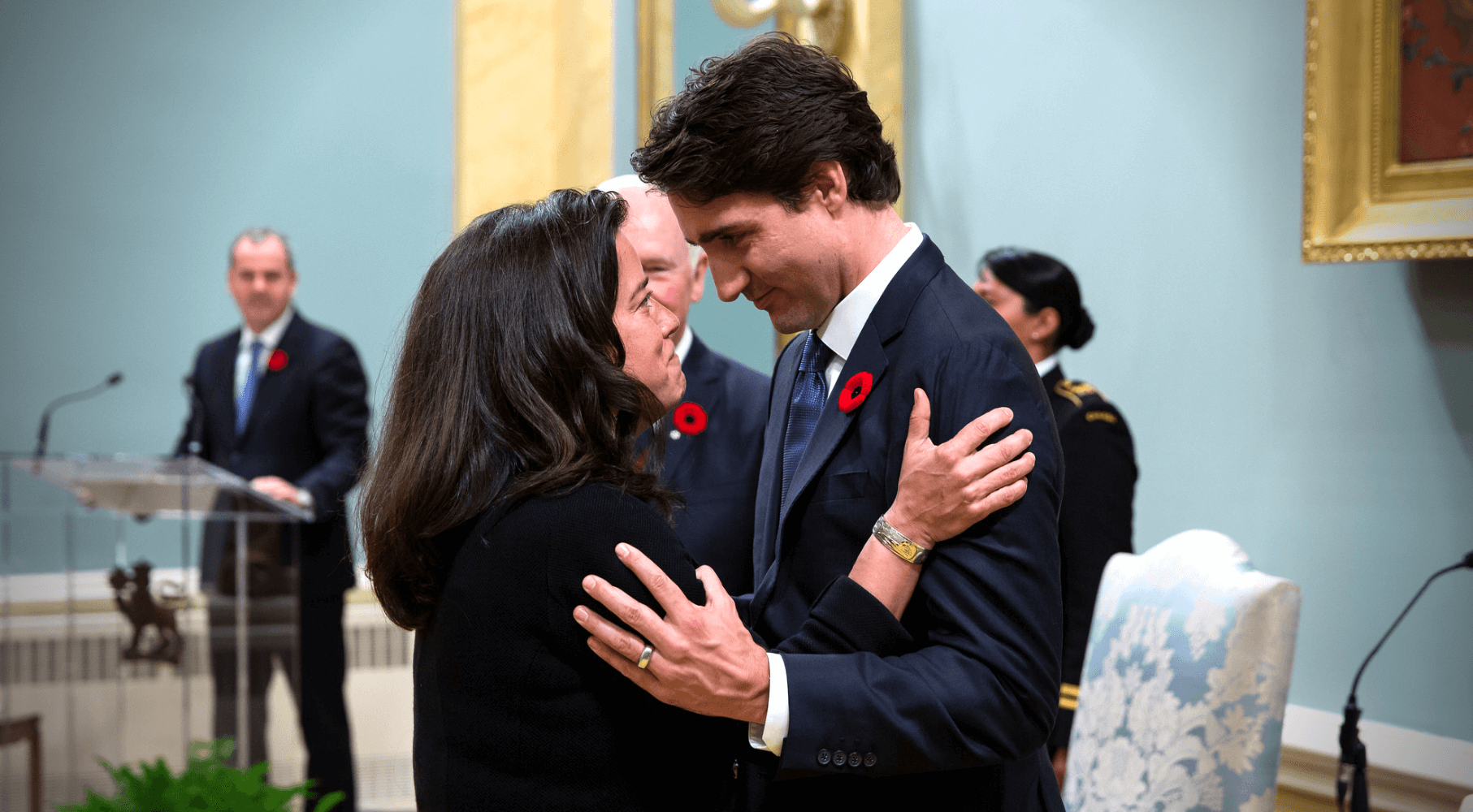

After the sudden resignation from cabinet of Jody Wilson-Raybould, Canada’s recently demoted justice minister and attorney general, a worrying question must be asked. Is Canada a society governed by the rule of law or not? Do political authorities call the shots or do the police, prosecutorial services and judges exercise their own independent judgment under the law about what cases to pursue and how?

The answer to these questions is suddenly a lot less clear than it was that fateful day when Meng Wenzhou stepped off the plane in Vancouver last December. Canadian authorities arrested Meng, CFO of China’s Huawei telecoms company, on an extradition warrant from the U.S. This led to a Chinese pressure campaign clearly designed to bully us into a political retreat from our position that this case was a pure example of the operation of the rule of law. The detention or resentencing of Canadians in China as well as other threatened actions appear to be in effect a punishment for Canada not being China, where the Communist Party is indisputably above the law.

Beijing does not accept that Canadian politicians cannot simply issue orders to any part of the state’s machinery, including the police, prosecution and judiciary. In China the Communist Party is above the law. In Canada, happily, no one is.

Or at least so many of us thought. The reason to question this assumption, and why we can be sure the Chinese are gleefully going to double down on their campaign against us, is because of the stories leaking out of Ottawa to the effect that officials at the very highest level of government, the Prime Minister’s Office, may have intervened in a proposed prosecution of a Canadian company, SNC-Lavalin.

Very quickly, the story is this: SNC got into trouble nearly a decade ago for bribery and corruption in some of its foreign dealings and this behaviour has been alleged by federal prosecutors to violate Canadian law. Because conviction on these charges would result in a 10-year ban on the company bidding on federal projects, the chief source of SNC revenue, the company has been waging an energetic campaign to replace a court prosecution with a negotiated “remediation agreement.” Such an agreement would cost the company some money but avoid the bidding ban, thus safeguarding SNC’s business model.

To the company’s consternation, federal prosecutors were not interested in playing ball but rather rejected the remediation route and planned to proceed with a prosecution. The potential scandal brewing in Ottawa revolves around the question of whether the Prime Minister’s Office attempted to intervene with Wilson-Raybould, to press her, either directly or indirectly, to order the prosecution to stand down in favour of remediation.

To date the government’s response, which is stonewalling of the highest order, only fans the flames of suspicion that there is some truth to these rumours, especially given that SNC has admitted to illegally funnelling money to the Liberal party in the past. This impression is further reinforced by the prime minister’s refusal to date to waive client-solicitor privilege and authorize Wilson-Raybould to speak candidly and publicly to confirm or deny what pressure she may have come under, including whether her recent surprise demotion to minister of veterans affairs might be related to her refusal to overrule the decisions of her independent prosecutors. So far, her silence seems eloquent and her resignation Tuesday may well break this story wide open.

But it’s not just the SNC case. In an indictment of the health of the rule of law in Canada would have to be added these charges: recent reports from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute detailing the breathtaking scale of Chinese money-laundering activities here, with an apparent inability to prosecute such crimes successfully; bizarre prosecution of Vice-Admiral Mark Norman in a case centring around allegations of political interference in military procurement at the behest of corporate interests; and former ambassador John McCallum’s defence of cutting a political deal to release Meng from the clutches of the Canadian court system. A disquieting pattern is emerging.

This pattern suggests that Canada is a country where the rule of law prevails only when it is in the interest of public authorities. That’s the system that prevails in China. If we don’t dispel that impression forcefully, Beijing will legitimately wonder why Meng is being subjected to the rigours of the law but not other business interests, who can use a political “get out of jail free” card.

The new justice minister, in his first interview, was at some pains to point out that when the courts have finished examining the extradition case against Meng he still has the discretion to refuse to authorize the extradition, including on grounds that to proceed would be contrary or damaging to Canada’s foreign policy.

This does not sound at all like a government committed to the rule of law, but one signalling to Beijing that a political deal may be in the cards after all. Beijing, like Canadians, is watching closely to see what kind of a country we really are after all.

Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.