By Kyoko Kuwahara, January 4, 2023

On November 27, 2022, Canada finally launched its new “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” one that represents a major step forward in its foreign and security policy to counter China’s challenge to the international order. The Trudeau government was cautious in developing its Indo-Pacific strategy so as not to aggravate its relations with China. But now it has made a 180-degree turn in its policy toward China, with the new strategy clearly stating the government’s concern over Chinese aggressive actions in the region. The strategy could be one of the most significant opportunities for Canada to develop closer coordination with Japan in the Indo-Pacific region.

From “Asia Pacific” to “Indo-Pacific”

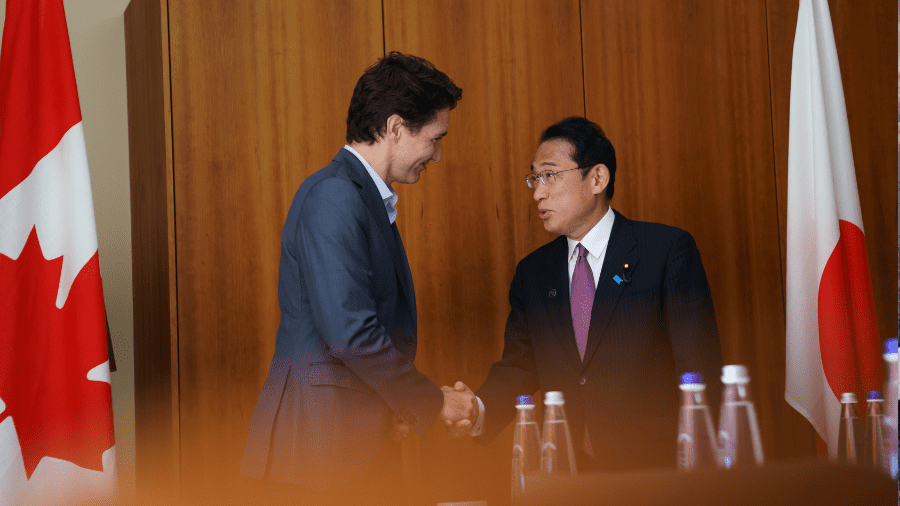

Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy is a clear message that the government has significant concerns over Chinese actions in the Pacific and Indian Ocean, and it is ready to work closely with Japan and the United States to confront this challenge. Nearly four years ago, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shared his “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (FOIP) vision with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the April 2019 Canada-Japan Summit, but the Canadian response was not so positive at that time. For years, the Trudeau government had preferred the concept of an “Asia Pacific,” which includes China, over the “Indo-Pacific” concept that targeted China as the major concern.

Canada has developed productive relations with China over the last decade. China is a major source for permanent and temporary immigration for Canada: according to 2021 Statistics Canada data, approximately 1.7 million Canadians are of Chinese descent, representing about 4.7 percent of Canada’s total population, with nearly half coming from mainland China. China is also Canada’s second-largest destination for new permanent residents, third-largest foreign tourist destination, and second-largest source of foreign students in 2019. Business ties with China are also deep, and the Chinese market offers significant opportunities for Canadian exporters. In short, Canada has a number of strong ties with China.

Canada’s changing views of China

China-Canada relations began to change in December 2018, when China arrested two Canadians – Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig – on espionage charges and detained them for more than 1000 days. This was widely seen as retaliation against the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou in Canada, following a US Department of Justice extradition request. Notably, Canadian public opinion of China also declined sharply following the arrest of the “two Michaels.”

In early 2018, before their detention, a Pew Research Centre survey indicated a 44 percent favourable view among Canadians towards China versus a 45 percent unfavourable view. Yet, in a follow-up survey in early 2019, this shifted to a 67 percent unfavourable view of China. And this trend has only increased. In 2022, months after Spavor and Kovrig were finally released, Canadians had a 74 percent unfavourable view of China. What these numbers mean is that in just three years, Canadian public opinion has increased its negative view of China by 29 points and decreased its positive view by 18 points (and this shift is even more pronounced if one looks further back, as the unfavourable view was a modest 27 percent in 2005).

This also coincided with a time when Canada was beginning to become concerned about the Chinese influence in Canadian society and politics. In the 2019 Canadian general election, at least 11 candidates reportedly received funds from China. Furthermore, it was later revealed that Chinese authorities have been monitoring their own citizens living abroad by setting up at least 102 “Chinese Overseas Police Service Centers” in 53 countries around the world. This was documented by a Spanish human rights organization in September 2019, which also said that China had established three such centres in Toronto and at least one in Vancouver.

Regarding these allegations of Chinese interference, Prime Minister Trudeau expressed serious concerns to President Xi Jinping at a closed-door meeting during the G20 Summit in November 2022. In reaction to this, Xi criticized Trudeau in front of the press over alleged media leaks of the substance of the meeting. Xi’s response may have been a “wolf warrior” style performance while being very much aware of the presence of the Canadian media in the vicinity.

In May 2022, Canadian government decided to exclude Huawei and ZTE from its 5G telecommunications network due to security concerns. Canada is finally beginning to align itself with other western countries to deal with the threat posed by a more aggressive China. In addition, during a visit to Japan in October, Foreign Minister Mélanie Joly stressed the importance of cooperation with Japan on a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Ocean” and the need for greater involvement in the Indo-Pacific region. It was against this backdrop that the “Indo-Pacific Strategy” was announced.

Launching Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy

Under the leadership of the Trudeau government, the Indo-Pacific Strategy calls for comprehensive economic, diplomatic, and security cooperation over the next 10 years with countries in the Indo-Pacific region, especially in Asia, such as Japan, India, South Korea, and Taiwan. At the same time, the strategy’s main focus is on China, and it strongly expresses a sense of caution toward China. The strategy mentions China 45 times (in the document’s 9300 words) and clearly states that the People’s Republic is an “increasingly destructive global power.” It goes on to say that Canada is affected by China’s “coercive diplomacy and non-market trade practices, such as forced labour,” and that Canada is firmly opposed to and will act against China’s dismissal of international rules.

On the other hand, the strategy also makes clear that Canada is ready to cooperate with China in solving global issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, global health, and nuclear proliferation. The strategy pointed out that distinction should be made between the actions of the Chinese government and the Chinese people. It also cites “the long-standing connections we share and the extraordinary contributions of Canadians of Chinese heritage to Canada [which will] will continue to bring diversity and depth to our relationship for decades to come.” Overall, the statement can be evaluated as a combination of a hard line and a cooperative line in its policy toward China.

In the North Pacific section, several pages were devoted to the importance of strengthening cooperation and collaboration with Japan and other countries in the region. Japan was mentioned 25 times as a positive factor for Canada. South Korea (19 times) and India (22 times) are also mentioned quite positively.

The strategy details Japan’s importance as the only G7 partner country in the Indo-Pacific region and, alongside Canada, one of the two largest economies among the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) participants. More specifically, it pointed out six shared priorities that were agreed upon between Canada and Japan in May 2021 for realizing the FOIP vision. They are (1) rule of law; (2) peacekeeping operations, peace-building, humanitarian assistance and disaster relief; (3) health security and response to infectious diseases; (4) energy security; (5) free trade promotion and trade agreement implementation; and (6) environment and climate change. The strategy also calls for the conclusion of the negotiations for the General Security of Information Agreement between Canada and Japan, and it also supports defence procurement cooperation between both countries.

In addition, it is worth noting that the strategy also stated the need for cooperation with Taiwan, which was mentioned seven times. It pointed out the importance of multifaceted cooperation with Taiwan in areas such as trade, technology, health, democratic governance, and disinformation measures. From a Canadian diplomatic and security perspective, this clear vision of Taiwan’s importance in the Indo-Pacific region should enhance future cooperation and partnerships with Taiwan.

Japan and Canada to jointly advance “Indo-Pacific Strategy”

Japan has been working actively to realize the “Free and Open Indo-Pacific” concept. As a matter of fact, Japan was the first to use the term when former Prime Minister Abe proposed the FOIP concept at the 6th African Development Conference (TICAD Ⅵ) in August 2016. Since then, the US, Australia, India, and other countries have been coming up with their own visions for the Indo-Pacific Ocean. In 2021, the Quad Leaders Meeting was launched to advance the FOIP concept with the participation of its four constituent countries, the US, Japan, Australia and India. On the other hand, Japan should be delighted and encouraged by Canada’s recent strategic shift. Canada is a natural partner for Japan, and one that shares common values such as democracy and observance of international rules. With this new Canada’s strategy, Canada-Japan cooperation will be further enhanced in the coming years.

Japan will assume the G7 chairmanship in 2023. In anticipation of this, Canada has indicated its willingness to work closely with and assist Japan in shaping its priorities, such as maintaining international order, engaging with the developing world, and addressing China-related issues. The world today is faced with daunting challenges including the Russian invasion into Ukraine as well as the security concern in the Indo-Pacific region.

Recognizing that Japan is situated in a complex and highly threatening post-war security environment, the Japanese Cabinet approved the National Security Strategy (NSS) on December 16, 2022. The NSS will guide Japan’s foreign and defence policy for the next decade and calls for closer security cooperation with Canada and other like-minded countries and regions in order to build and expand a multilayered network among allies and partners and to strengthen deterrence.

The next G7 Summit will be a critical moment for member states to meet key global challenges. Canada and Japan, as natural partners, should work closely in the Indo-Pacific region and press China to observe the rules-based international order.

Kyoko Kuwahara is a Visiting Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.