Growing expectations of a possible peace deal for Afghanistan should not overshadow the country’s problems and challenges, writes Irfan Yar. Canada in particular has an interest in the future of Afghanistan.

Growing expectations of a possible peace deal for Afghanistan should not overshadow the country’s problems and challenges, writes Irfan Yar. Canada in particular has an interest in the future of Afghanistan.

By Irfan Yar, February 5, 2019

On Tuesday, the Taliban’s representatives once again came to a negotiation table and discussed the peace talks with its Afghan opponents in Moscow. Diplomatic talks between the US and the Taliban has also increased, with both sides reportedly agreeing to the preliminary outlines of a possible peace deal after several days of negotiations in Qatar, and so too have the expectations for peace. But given the multifaceted problems and complex situation in Afghanistan, unfortunately the peace talk is less likely to change the situation in the war-torn country. The problem demands a more holistic approach.

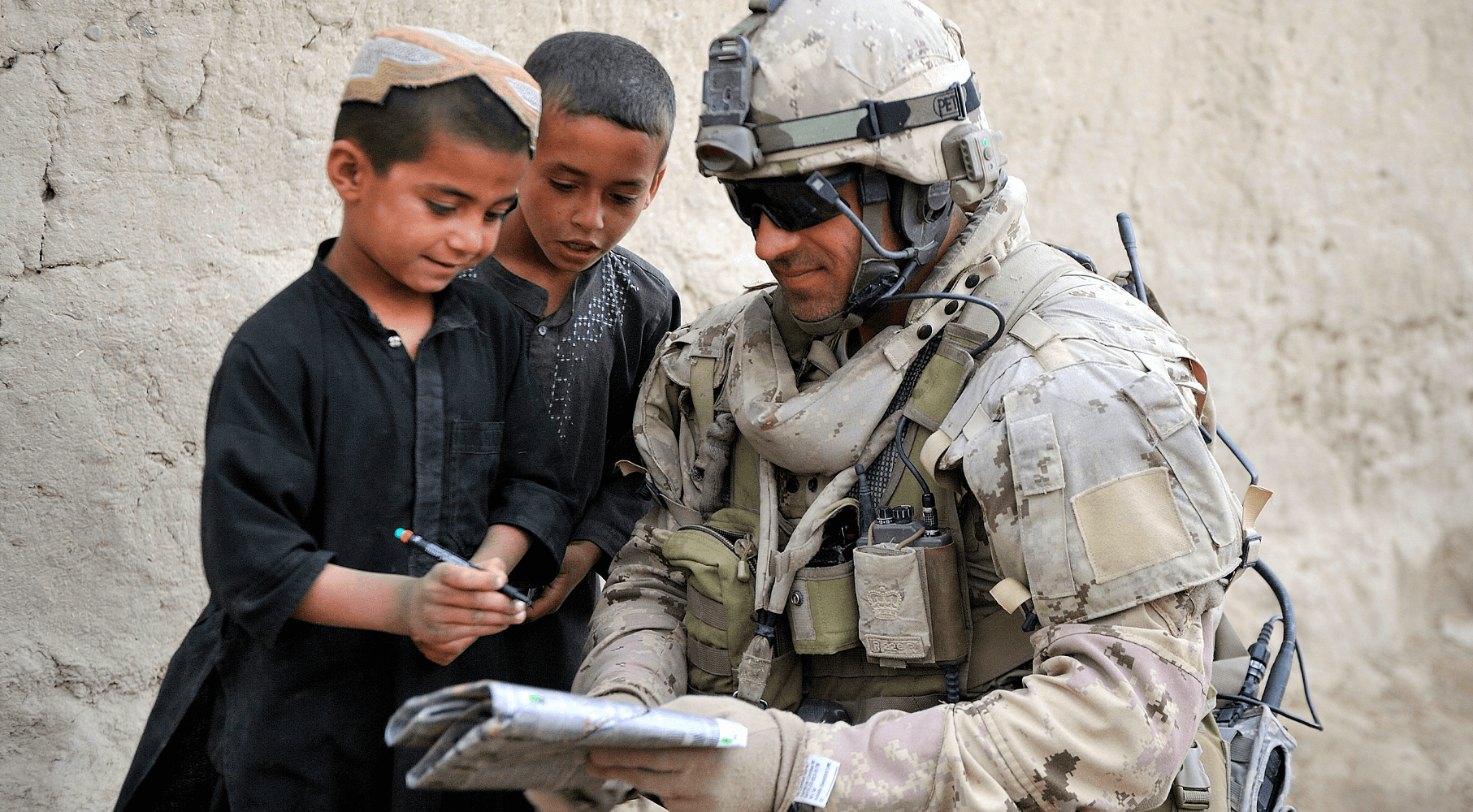

It has been 17 years since the start of Operation Enduring Freedom, yet Afghanistan remains mired in escalating conflicts. More than 34,000 civilians have been killed and hundreds of thousands have fled their homes as a result of direct violence. Canada has been among the leading countries that sought to bring stability to the war-weary country. During its mission to Afghanistan, Canada lost well over one hundred troops and spent billions of dollars but to no avail. The security situation is constantly deteriorating in the country, and the violence shows no sign of abating. The shifts taking place in Afghanistan not only impact regional security, but its spillover can be felt around the world. This article talks about how the dynamics in Afghanistan influence Canada.

Canada’s engagement in Afghanistan

Canada’s military mission began in early 2002, shortly after the US-led invasion dislodged the Taliban regime that had harbored terrorists responsible for the 9/11 attacks. Canada’s military involvement soon rapidly increased and so did its expenses and causalities. As part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), Canada shouldered the responsibility to guard Kandahar, which once served as the capital of Taliban government. Although the Canadian Armed Forces helped to restore order to the restive province, Taliban militants remained a dominant force in the suburb of the city.

The Canadian military role in Afghanistan officially ended in 2011. Yet Ottawa continued its non-combat assistance to the country. Besides its signature project of Dahla Dam in Kandahar, Canada has disbursed funds for reconstruction, humanitarian relief, and building schools. However, this non-military expenditure was relatively modest compared to the resources that had been expended prior to 2011.

How the shifts in Afghanistan influence Canada?

Canada ended its intervention in Afghanistan without achieving its goal – ensuring a stable Afghanistan. Yet, despite the geographic distance that separates the two countries, the situation in Afghanistan still has an impact on Canada’s national interest in several ways.

First, Afghanistan’s security situation has been increasingly volatile in recent years. The Afghan defence force remains weak and is unable to independently take on an emboldened Taliban, which is active across 70 percent of Afghan territory. Today, the country is a breeding ground for extremist groups. Besides the regional security, a destabilized Afghanistan also poses a serious threat to international security. For instance, under the Taliban’s rule, Pakistani terrorist training centers were shifted to Afghanistan where Islamists were trained and sent to Kashmir. Similarly, Al-Qaeda used Afghanistan as a launching pad for its own terrorist operations.

As part of the proposed US-Taliban peace deal, the insurgents pledged that they would cut ties with Al-Qaeda. But given that Al-Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan operate under the Taliban and share common enemies, both groups still enjoy warm but informal relations. If the Taliban takes over Kabul once again with the same ideology, there is no sign that co-operation with Al-Qaeda would not continue in future.

Second, roughly 158 Canadians have traveled abroad to join Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. With the territorial defeat of the so-called Islamic State, a number of Islamic State militants have made their way to Afghanistan. The ‘Islamic State’ in Afghanistan, also known as the Islamic State of Khorasan (ISK), has rapidly mushroomed and now exercises a strong influence across the country. If ISK gains more ground, there could be an influx of the Western foreign fighters to Afghanistan. Many French and British jihadists have already joint ISK in Northern Afghanistan; Canadian foreign fighters might very well follow suit.

Third, an unstable Afghanistan remains an economic drain on Canada. The Afghan mission has cost Canada $18 billion, the bulk of which has been spent on military operations. Canada still contributes $110 million a year to support the Afghan National Defence and Security Forces. A self-reliant and stable Afghanistan would not require this continuing support.

Fourth, there is the problem of refugees. In Afghanistan, civilian causalities have peaked in recent years. Conflict has pushed millions of people out of the country. An estimated five million Afghan refugees have fled to neighboring countries (Iran and Pakistan) and to Europe. In addition, every year a portion of Afghan refugees, for example 1354 in 2016, also arrive in Canada in search of asylum. While these refugees might eventually provide a boost to Canada’s economy, Ottawa also needs to ensure that they don’t become a burden too. Thus, if Afghanistan is safe and the lives of the people are protected, we could expect a much lower migration trend.

What should Canada do for Afghan peace

After investing a great deal of blood and treasure, Canada should not forget Afghanistan. The country’s voice still matters for Afghanistan.

Ottawa should mount diplomatic pressure on those countries like Pakistan, which have a history of sponsoring extremist militants and terrorists in Afghanistan. Pakistan has a notorious history of exercising significant influence over the Taliban. Working with its international partners, Canada could exert greater diplomatic pressure on Pakistan to urge it to take a harder line on these extremist groups.

Unlike the US, Canada does not independently audit the money it deposits into Western trust funds for international aid. According to the Library of Parliament, Canada has donated more than US$3 billion in foreign aid to Afghanistan, of which US$763.7 million went to Afghan reconstruction and other US$87.2 million to train Afghan police. A big chunk of Canada aid, unfortunately, went to the pockets of the corrupt local officials and warlords, making the projects less effective. Canada needs to make policies that ensure its money goes into the right hands.

Notably, there can be generous economic opportunities for both countries. Afghanistan sits atop US$3 trillion of untapped minerals, including iron, copper, gold, petroleum, natural gas, talc, high-quality gemstones, chromite, zinc. In 2007, a Vancouver-based company, Hunter Dickinson bid on the Mess-Aynak, the second largest copper ore body in the world, but lost to China Metallurgical Group. The exploration of these resources can bring a huge wealth to both countries and directly contribute to peace.

Recently the government of Canada is working on a plan to offer a shelter to 300 Sikhs and Hindus families who are being persecuted in Afghanistan. Such minorities have been an integral and active part of Afghan society and their decision to leave Afghanistan is a big loss for the country. Instead of these ad hoc approaches, Canada should actively work with its international allies for the long-term stability in Afghanistan.

The shifts taking place in Afghanistan do have an impact on Canada. If Afghanistan falls into the hands of extremist groups, Canada might once again find itself returning to the country, in another costly military mission. To curb terrorism in Afghanistan, Canada should use its diplomatic muscles. It is also important for Canada to go one step beyond its NATO-centric foreign policy and adopt a new and broader policy toward Afghanistan based on economic opportunities. Indeed, India’s efforts to ensure a prosperous Afghanistan are commendable, and should serve as a model for other countries.

Irfan Yar is a counterterrorism analyst, currently at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute as a Research Intern.