Middle powers with strong democratic foundations and progressive outlooks on global trade and economic engagement are sorely needed in the region, writes Amitendu Palit.

Middle powers with strong democratic foundations and progressive outlooks on global trade and economic engagement are sorely needed in the region, writes Amitendu Palit.

By Amitendu Palit, July 20, 2021

The Indo-Pacific was hardly discussed when Japan’s then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe alluded to it in his address to the Indian Parliament on August 22, 2007. Abe’s description of the confluence of the Indian and Pacific oceans as “a dynamic coupling of seas of freedom and of prosperity” was an important statement on the strategic significance of the region.

Since then, the Indo-Pacific has grown into a key battleground for the strategic contest between the US and China. The quest for influence is being sought through control over infrastructure assets and management of critical supply chains. The geo-economic and political upheavals caused by COVID-19 have further exacerbated the contest in the region and also accelerated a range of pre-existing tensions between Beijing and its neighbours. Managing these tensions and helping the region to progress in a stable and peaceful manner requires the support of global middle power democracies like Canada working closely with India, Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom and others.

The Superpower Rivalry

The geo-economic salience of the coupling of the Indian and Pacific oceans became evident after China announced the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) in 2013. By building land, sea and digital infrastructure, the BRI aims to connect markets, cultures, communities and institutions in Asia, Africa and Europe across the vast stretches of the two oceans and thousands of kilometres of land routes. The BRI’s advance underpinned the strategic importance of the Asian continent – woven around the two oceans – as a distinct geo-economic and geo-political environment.

The geo-economic salience of the coupling of the Indian and Pacific oceans became evident after China announced the Belt and Road initiative (BRI) in 2013. By building land, sea and digital infrastructure, the BRI aims to connect markets, cultures, communities and institutions in Asia, Africa and Europe across the vast stretches of the two oceans and thousands of kilometres of land routes. The BRI’s advance underpinned the strategic importance of the Asian continent – woven around the two oceans – as a distinct geo-economic and geo-political environment.

The need to counter China’s strategic influence through the BRI was a key factor underpinning this shift in emphasis. Meaningful partnerships with key strategic allies like Japan, India, Australia, Korea and Taiwan were declared essential for tackling an increasingly belligerent China.

The US declared its own vision of the Indo-Pacific within a year of President Trump assuming office. President Trump’s reference to the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ (FOIP) at the APEC Summit in Vietnam in November 2017 was an expansive shift of the US perspective on Asia, compared with the narrower “pivot” or “rebalance” to Asia of the Obama administration. The depth of the shift was clear in the FOIP’s equal emphasis on both the Indian and Pacific oceans. The former was much less in focus in the Obama administration’s regional strategy. It must be noted though that the FOIP was alluded to by Prime Minister Abe in his speech at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) at Kenya in August 2016, nearly a year before the US pronouncement.

The US comprehensively acknowledged the vitality of the Indo-Pacific in its National Security Strategy and the Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific. US economic interests in the region were noted as being equally prominent as its security concerns. The need to counter China’s strategic influence through the BRI was a key factor underpinning this shift in emphasis. Meaningful partnerships with key strategic allies like Japan, India, Australia, Korea and Taiwan were declared essential for tackling an increasingly belligerent China. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 provides the framework for the US strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

The US comprehensively acknowledged the vitality of the Indo-Pacific in its National Security Strategy and the Strategic Framework for the Indo-Pacific. US economic interests in the region were noted as being equally prominent as its security concerns. The need to counter China’s strategic influence through the BRI was a key factor underpinning this shift in emphasis. Meaningful partnerships with key strategic allies like Japan, India, Australia, Korea and Taiwan were declared essential for tackling an increasingly belligerent China. The Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018 provides the framework for the US strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

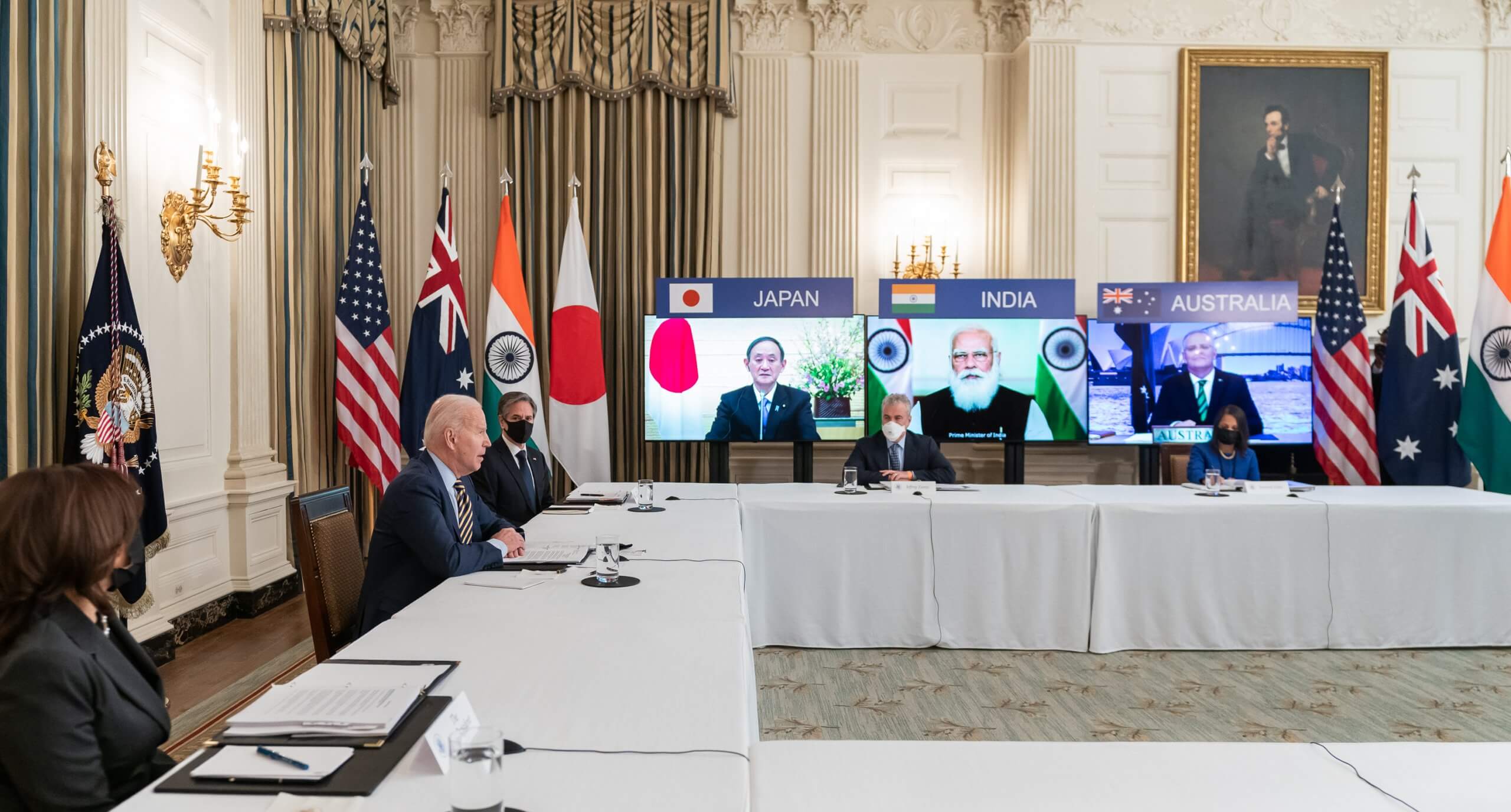

As China advanced on the BRI, so too did partnerships between the US and its core allies in the Indo-Pacific. Nothing symbolizes the enthusiasm behind such alliances more than the Quad – the quadrilateral partnership between the US, Japan, India and Australia. Buoyed by the momentum following the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, all four of the Quad members have now agreed to work on the “most urgent of global challenges,” including tackling COVID-19, setting standards for new technologies, and addressing climate change.

Infrastructure and Influence

The Indo-Pacific is characterized by economic heterogeneity, which is a source of the region’s economic strength. Economies complement each other in their different patterns of resource endowment, wealth, institutional and innovative capacities, human skills and technological competences. This explains the growth of major supply chains across the Indo-Pacific that draw in location-specific efficiencies.

The Indo-Pacific is characterized by economic heterogeneity, which is a source of the region’s economic strength. Economies complement each other in their different patterns of resource endowment, wealth, institutional and innovative capacities, human skills and technological competences. This explains the growth of major supply chains across the Indo-Pacific that draw in location-specific efficiencies.

In the conjoined geography of the two oceans, high-income industrial OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) economies – US, Japan, Australia, Korea, New Zealand, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore – coexist with large middle and lower-middle income economies like China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, South Africa and the Gulf economies. The larger ones are increasingly choosing sides in the battle of infrastructure-based influence being played out among the superpowers. Some among the relatively larger economies (e.g., Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Malaysia, Iran) along with many of the smaller ones (e.g., Cambodia, Myanmar, Nepal, Maldives, Mauritius, Seychelles) are experiencing the heat of the battle for influence in varying degrees.

The BRI’s generosity, though, comes at a price. Strategic loyalty to China is an implicit condition.

The BRI promised large concessional debt funds for building critical infrastructure to many of the regional economies. The supposedly “no-strings-attached” funding was a radical departure from Western donor and multilateral institutional resources, the latter being otherwise laced with tough conditions, including deep structural reforms, institutional overhauling, as well as demands for high standards of domestic social, political and civil society performances.

The BRI’s generosity, though, comes at a price. Strategic loyalty to China is an implicit condition. Such implicit costs are compounded by unsustainable debt burdens and rising environmental fragility for many of the recipient economies. Nonetheless, the ease of obtaining funds has led to China’s rise as a provider of infrastructure funding and obtained for it commensurate strategic goodwill from many countries in the region.

The realization has led to the largest global donors, notably the G7, committing to partner with key Indo-Pacific stakeholders (e.g., Australia, India, Korea, South Africa) in investing in quality infrastructure development in the region. These third-country partnerships have the ostensible objective of counterbalancing China’s influence in parts of the region that are infrastructure-deficient. The competition for influence was thus set to intensify as the US and China organized their respective allies along infrastructure and connectivity efforts.

Supply chain ramifications

Competitive impulses, driven by security interests, are triggering a reorganization of regional supply chains in the Indo-Pacific.

Competitive impulses, driven by security interests, are triggering a reorganization of regional supply chains in the Indo-Pacific.

The Biden administration’s 100-day review of supply chains clearly indicates that economic efficiency and low costs – which for years encouraged US businesses to pursue geographical fragmentation of production – would no longer be prioritized over US security and national interests. Excessive sourcing dependency, the review suggests, has made the US vulnerable to supply disruptions in various critical industries such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. This understanding leaves little doubt over the Biden administration’s prioritization of a significant decoupling from sources of excessive concentration, particularly China, and diversifying elsewhere.

China has stated its intention to resist US efforts at decoupling. With the passage of time, the superpower rivalry for controlling strategically important industries, specially those impacting national security (e.g., semiconductors, pharmaceuticals, critical minerals, telecommunication, digital financial services, energy, shipping), would experience greater friction. The friction would reverberate across these industry supply chains in the Indo-Pacific, leading to a struggle to align between competing standards, systems and functional practices. This is becoming evident in areas like 5G communication networks, which is witnessing robust competition between Chinese and non-Chinese choices.

As both superpowers look to locate more production at home, they might also devote energy in building an economic architecture for the region. Such an architecture… is essential for long-term economic prosperity, environmental sustainability and political stability of the region.

Making supply chains resilient by reducing external vulnerabilities and enhancing national security is a common priority for both the US and China. The thrust of President Biden’s supply chain review resonates with President Xi’s dual circulation strategy, with both countries looking to domesticate supply chains for greater control over strategic industries to minimize adverse security impacts.

As both superpowers look to locate more production at home, they might also devote energy in building an economic architecture for the region. Such an architecture – with modern and inclusive rules for trade, investments and mobility of people, technology and data – is essential for long-term economic prosperity, environmental sustainability and political stability of the region. To develop and maintain this architecture requires global and regional middle powers, including Canada, to play a proactive role.

The Canadian role

A purposeful contribution to the growth of a sturdy and robust rules-based trade and economic framework in the Indo-Pacific should come naturally to Canada. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – signed by major Indo-Pacific economies like Japan, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam – is already functional. As a prominent member and the second largest economy within the CPTPP, Canada can work with the rest, particularly Japan and Australia, in expanding the CPTPP’s acceptability as an economic template for the region.

A purposeful contribution to the growth of a sturdy and robust rules-based trade and economic framework in the Indo-Pacific should come naturally to Canada. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – signed by major Indo-Pacific economies like Japan, Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam – is already functional. As a prominent member and the second largest economy within the CPTPP, Canada can work with the rest, particularly Japan and Australia, in expanding the CPTPP’s acceptability as an economic template for the region.

The UK has already shown interest in joining the CPTPP. Enlarging the CPTPP membership to include more prominent middle powers from the region, including India, Indonesia, Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and South Africa, would make it an inclusive and widely acceptable choice for the rest of the region.

Canada is well poised to further engage with the Indo-Pacific as an active member of the G7 and G20… Canada can capitalize its goodwill in the region to participate actively in efforts to evolve durable regional frameworks.

Canada is well poised to further engage with the Indo-Pacific as an active member of the G7 and G20. The G7’s emphasis on “build back better” in the aftermath of COVID-19 and the emphasis on funding quality infrastructure through transparent norms in the Indo-Pacific has already brought Canada into the space for sustainable “green” infrastructure development in the region. Its role in sustainable development and public health in the Indo-Pacific can grow if combined with the G20’s commitment to expand equitable access to vaccines and strengthen efforts to achieve sustainable development.

Canada is well poised to further engage with the Indo-Pacific as an active member of the G7 and G20. The G7’s emphasis on “build back better” in the aftermath of COVID-19 and the emphasis on funding quality infrastructure through transparent norms in the Indo-Pacific has already brought Canada into the space for sustainable “green” infrastructure development in the region. Its role in sustainable development and public health in the Indo-Pacific can grow if combined with the G20’s commitment to expand equitable access to vaccines and strengthen efforts to achieve sustainable development.

Several Indo-Pacific countries are relying heavily on supplies from the World Health Organization’s COVAX pool of vaccines. As a prominent contributor to COVAX, complemented by its bilateral efforts to work on expanding global vaccine supplies, such as with India, Canada can capitalize its goodwill in the region to participate actively in efforts to evolve durable regional frameworks.

Due to current geopolitical frailties, shaped by the clear rivalry between the world’s superpowers that is sure to continue after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indo-Pacific remains vulnerable to possible reversals in its trajectory towards economic prosperity and sustainability. Middle powers with strong democratic foundations and progressive outlooks on global trade and economic engagement are sorely needed in the region. Together, they will be able to work together to build frameworks and institutions to minimize the damages arising from frictions and enable the region to stay committed to the long-term goal of ensuring better and safer living standards for its people. The contribution that Canada can make in this regard can hardly be overstated.

Amitendu Palit is Senior Research Fellow and Research Lead (trade and economic policy) at the Institute of South Asian Studies in the National University of Singapore. He can be reached at isasap@@nus.edu.sg. The views expressed here are his own.