By Linda Blade

February 21, 2023

One of the most consequential innovations in the competitive sporting world in years has been the recent decision to allow male-bodied athletes to compete against biological women in the female category. This decision has been controversial, not least because the scientific evidence is clear that male-bodied athletes – especially those who have gone through puberty – enjoy insurmountable physical advantages over female competitors, independently of the level of testosterone in their body (Pike, Hilton, and Howe 2021, 16). And since it is bodies that compete in sport, and not subjective gender identities, the result is that the very existence of a separate female category in sport is threatened.

Astonishingly, given how deeply the interests and rights of female athletes are affected by these momentous policy changes in sports, to date little is known about how female athletes feel about these changes: about how they think about the integrity and fairness of sporting competitions that pit male bodies against female ones; how they assess the physical risks of such competition for female competitors; and how free they feel to express their legitimate views on these issues.

The absence of input by female athletes happens not because they don’t have strong and well-justified views about these issues, but because every effort has been made by sporting officials and the government of Canada to prevent the public from knowing about their frustration, sadness, and unhappiness at being subjected to such important changes without so much as a by-your-leave.

That silence has now been broken.

It has not, however, been broken by government and sporting authorities coming to their senses and welcoming an open, constructive, and truly inclusive conversation about the policy around women’s sport. It has been broken by an Access to Information (ATIP) request to Sport Canada by the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, which has resulted in the release of a major inquiry into the attitudes and feelings of elite or “high performance” (HP) female athletes; an inquiry which the government of Canada tried, but failed, to obstruct and only released because the law required them to do so.

The Sport Canada report, Canadian High-Performance Female Athletes’ Voices: Transgender Inclusion in Elite and Olympic Sport Guidelines, is a survey undertaken in 2022 by British researcher Cathy Devine and Canadian professor Leslie Howe (Devine and Howe 2022). It is the first attempt ever undertaken in Canada to consult the women who must live every day with the consequences of the new policies that rank transgender inclusion in Canadian sport as more important than safety, fairness, or equality of the sexes.

How did we get here?

This whole controversy arises because of a decision – namely, that athletes whose subjective “gender identity” conflicts with the biological reality of their bodies’ sex must be “included” – that means, and can only mean, one thing: that subjective gender identity must trump objective biological sex and therefore participation in male and female sport categories should be determined solely by an athlete’s gender identity.

Given that male bodies enjoy an overwhelming physical advantage over female bodies in sport (Pike, Hilton, and Howe 2021, 13-14), such a concept of “inclusion” inevitably gives rise to two obvious thoughts:

- This kind of inclusivity is asymmetrical: a woman self-identifying into the men’s category would not have the same kind of success that a man moving in the opposite direction would enjoy.

- The group that will be most harmed should have a say in any policy that alters the dynamics of their participation.

Yet the authorities in Canadian sport who rushed to compel national sports organizations (NSOs) to adopt a policy that threatens to completely undermine the female sports category have been clear that they cannot or will not engage with anyone criticizing their policies with these logical deductions.

The authorities that will not discuss these legitimate concerns aren’t just any authorities, though. One entity bears overwhelming responsibility for the policy quagmire that is now women’s sport in Canada: the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES).

A brief history of the CCES might offer context.

Arising like a phoenix out of the ashes of the Ben Johnson Olympic doping scandal (Montague 2012), the CCES represented “the beautiful new fence around the sacred principle of ‘the level playing field’ in sport” (Blade with Kay 2020, 27). For most Canadian sports personnel of that era, the CCES exemplified the “government’s promise that systematic cheating in sport would never again be tolerated” (Blade with Kay 2020, 27). Its primary mandate was to spread the anti-doping message and provide NSOs with the means to stamp out such forms of cheating.

The CCES met its mandate successfully for about a decade. Then suddenly, in 2016, it published something utterly unexpected: Creating Inclusive Environments for Trans Participants in Canadian Sport (Trans Inclusion in Sport Expert Working Group 2016). The document was preceded by no warning, based on no serious research and, above all, did not follow from any consultation with female athletes.

Without an iota of consideration given to the right of the female athlete to fair competition, the CCES implored NSOs in Canada to include male-born persons into the female category based upon self-proclaimed gender status alone. No surgery or hormonal mitigation was to be required. And the CCES required no consistency: a person could compete as a man one day and as a woman the next at their choosing. Back and forth at will.

The CCES decided that it would henceforth be deemed hateful for an NSO to either question or attempt to verify biological status via medical testing of any sort. Yet, CCES doping control would continue unabated.

This meant that a female athlete would be forbidden from using any hormones whatsoever, since doing so is a form of doping and all agree that it confers an unfair advantage upon the user relative to her female peers. The blatant doping employed in the past by then-Eastern Bloc countries, of which East Germany was a prime example, was part of the reason CCES was created in the first place, the better to weed out such obvious unfairness. The fact that this same organization now argues passionately (but with no scientific support) for the intrusion of male-bodied athletes into women’s sport is both disappointing and scandalous.

Thus, an athlete born male and reaping all the undeniable and permanent physiological and anatomical advantages of passing through puberty as a male – bigger bones, larger muscles, bigger heart and lung size, and high testosterone – could choose his competition category at will, while the athlete born female would be punished under the existing rules should she add one drop of extra testosterone in an attempt to level this new playing field.

When the CCES and its “Expert Working Group” (EWG) met to formulate the policy in 2014, one would have thought that someone on this elite sports committee might have pointed out the glaring flaw in their logic. One would have thought that the EWG might have wanted to consult with the female athlete sector, given that their new philosophical framework was bound to have an overwhelming impact upon Canadian women and girls.

One would have thought this. But no! According to footnote 3 of the CCES transgender guidance document:

Two telephone focus groups with female high-performance cisgender athletes were arranged and promoted through AthletesCAN. Unfortunately, only two athletes were available at that time, both of whom were interviewed. (Trans Inclusion in Sport Expert Working Group 2016, 5)

Two women. In all of Canada. And no hint provided as to what they said. That was the extent of the CCES “consultation” on a policy shift both draconian and devastating to female athletes. It was easily far more damaging than anything seen since women joined the sports community through their own sex-based sporting category over 100 years earlier.

Lest the reader’s power of imagination should fail, consider the following two sample sports contexts and the impact that this strange, new “ethical” landscape would henceforth look like for women and girls in Canadian sport.

Example 1: Canadian Powerlifting Union (CPU) transgender policy

The CPU (circa 2019), following the CCES recommendations on gender inclusion, adopted the following policy: “At both recreational and competitive levels, an individual may participate in their expressed and identified gender category” (Canadian Powerlifting Union 2019).

Yet inspection of world powerlifting records show that males have an enormous advantage in this sport as follows:

Squats = 54.5 percent male advantage

Bench Press = 65.3 percent male advantage

Deadlift = 54.9 percent male advantage. (Keys 2022)

Yet despite possessing this knowledge, the CPU followed the CCES guidelines and decided to permit male-bodied athletes to compete against its female participants. It did so, moreover, in a way that contravenes the much stricter transgender regulations of even its own international governing body, the International Powerlifting Federation (IPF). The IPF requires a trans-identifying male competitor to mitigate serum testosterone levels severely for an entire year (IPF 2022).

In other words, CPU authorities ignored what they knew to be an obvious unfairness for its female competitors in contravention of the international regulations of its sport in order to appease the CCES.

Example 2: Rugby Canada transgender policy

While that is bad for the women in powerlifting, at least powerlifting is an individual sport and does not involve human collisions and contact. One would think that the safety risk of having male players join female players in a contact sport would inspire a more careful review of transgender inclusion. Astonishingly, no. The Rugby Canada gender inclusion policy statement is as alarming as the CPU policy, and is also in conflict with its global sports federation (World Rugby 2021a). Rugby Canada’s transgender policy begins in a similar way to the CPU policy but goes even further:

At both recreational and competitive levels, an individual may participate in their expressed and identified gender category. An individual will, at the time of registration, identify their gender category for the playing season and may request a change in gender category at any time during a playing season and such request will be considered by Rugby Canada. (Rugby Canada 2019, [4])

Rugby Canada insists on hewing to the CCES recommendations despite World Rugby sharing an alarming conclusion of the thorough scientific review it undertook in 2020:

[T]the situation where a typical player with male characteristics tackles a typical player with female characteristics increases the magnitude of known risk factors for head injuries by between 20% and 30%. In the event of smaller female players being exposed to that risk, or of larger male players acting as opponents, the risk factors increase significantly, and may reach levels twice as large, at the extremes. (World Rugby 2021b).

Despite much ado about “safe sport” considerations preoccupying Canadian NSOs over the past decade – including ample coverage of the concussion protocol – the possibility that a female rugby player’s exposure to serious head injury would increase by 20 to 30 percent during contact with a male body on the pitch seems to have made zero impression upon Rugby Canada’s leadership.

It gets even worse for the women, as Rugby Canada’s policy goes on to add:

When Rugby Canada has the authority to determine participants’ use of washrooms, change rooms, and other facilities, Rugby Canada will permit individuals to use the facilities of their gender identity. (Rugby Canada 2019, [3])

Not only does a female player suffer significantly increased risk of an injury to her head, neck, or back as a direct result of including a male body on the pitch, when she retreats to her locker room in search of shelter and privacy she might encounter a naked man there, in whose presence she’d be expected to shower and change, without comment, much less complaint.

To summarize, these CCES-inspired policies being enacted by Canadian NSOs not only fail to meet international standards of fairness and safety, they also signal the following set of possibilities:

- Men could participate in women’s competitions, winning team positions and prizes.

- Men could be in women’s locker rooms.

- Men could be in women’s hotel rooms, where team members are expected to bunk together while on the road.

Female athletes might be forgiven for viewing this surreal set of facts as a creeping (and creepy) destruction of their sport. As the Devine and Howe study (2022) reveals, feelings of incredulity, helplessness, anger, and sadness abound.

In the historical context these sentiments are not new. The concerns of women about emotional and sexual abuse have often been deliberately ignored in sport as was the case in 2022, for instance, by Canadian gymnasts calling for investigation into the toxic, abusive environment that prevails in their sport (Devine and Howe 2022, 8). But the idea that a male athlete, with all attending advantages, can simply self-declare into the women’s sports category has been a bridge too far for many.

The ultimate humiliation, however, surely must be the unabashed statement by the CCES in its 2016 document that men who identify as transgender do maintain an advantage but that it doesn’t matter:

The Expert Working Group acknowledges the concern that transwomen athletes who grew up biologically male and who do not undergo hormonal [or surgical] intervention may be at a competitive advantage when competing in high-performance women’s sport. Nonetheless, it is recognized that [trans-identifying males] are not males who became females. Rather these are people who have always been psychologically female, but whose anatomy and physiology, for reasons yet unexplained, have manifested as male. (CCES 2016, 20)

The CCES’s presumption seems to have been that the female athlete in Canada has a duty to adhere to a system of belief that privileges the subjective mental states of male persons above the female athlete’s right to a safe and fair environment in which to practise her sport. This presumption also ignores the fact that it is neither psyches nor identities that compete on the playing field, but bodies.

Concurrently, the Canadian parliament passed Bill C-16 (Canada 2016) suggesting that if citizens – presumably including female athletes and other sports personnel – fail to properly acknowledge and accommodate the momentary self-declared identity of the male athlete it might even be a crime.

This ideological shift across the Canadian legislative and cultural landscape launched two distinct sets of rights on a collision course: the “sex-based rights” of women and girls to fairness and safety versus the rights of citizens generally to their “gender identity” and/or “gender expression.”

On the one hand, the CCES recommendations clearly violate the sex-based human rights of female athletes. On the other hand, interpretation of Bill C-16 ostensibly leads many NSOs to accept that the female athlete has neither the right to express alarm nor to deny access to a man who self-identifies in a particular way at a given moment.

But female athletes in Canada do have rights. As Devine and Howe point out:

Both the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Human Rights Act outline that the Canadian Government should not discriminate against girls and women on the basis of sex in relation to laws, programs, employment and services. (2022, 6)

Even while the entirety of Canadian sports seems to have spent much time since 2016 genuflecting to the new belief system espoused by the CCES and the current government, pressure to address the growing chorus of alarm coming from frightened athletes, coaches, and administrators was reaching a crescendo. To its credit, Sport Canada responded by commissioning this survey, asserting that:

Sport Canada has an ethical imperative to consult with both female athletes regarding eligibility for opposite sex categories, based on gender identity, and with transgender athletes regarding their preferred inclusion options. Further, it is important that this stakeholder engagement is conducted with the athletes themselves, rather than organizations with a remit to represent them, given the research shows that the views of the athletes may well be in direct conflict with the stated position of a range of sporting agencies. (Devine and Howe 2022, 8)

The aim of the study was, essentially, to “address the gap in stakeholder consultation in Canada by soliciting the voices of Canadian high-performance female athletes in relation to transgender inclusion strategies at high-performance levels” (Devine and Howe 2022, 8).

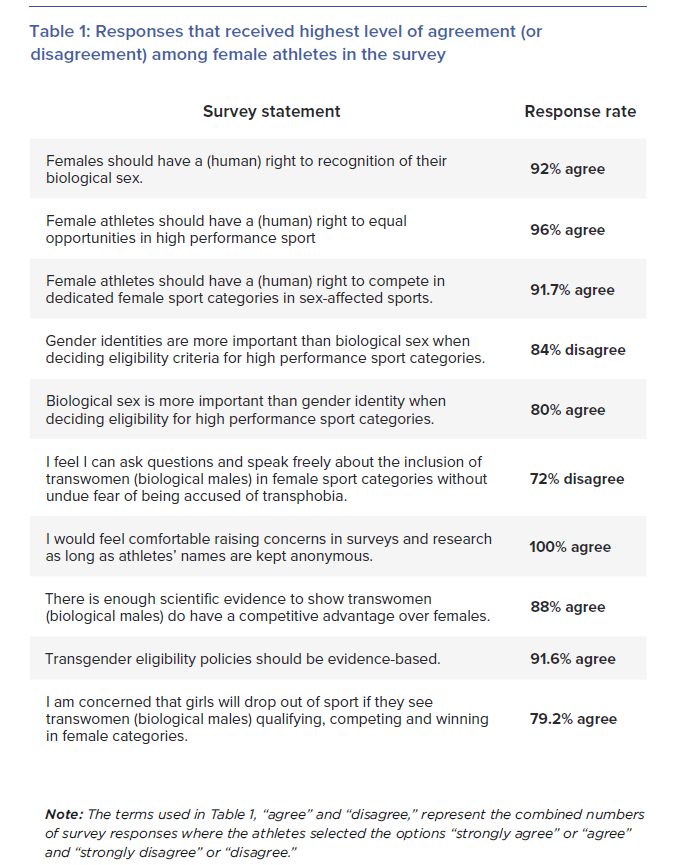

Despite the prevailing fear amongst female athletes of being accused of bigotry and transphobia, Devine and Howe were successful in finding 25 current and former high-performance female athletes in Canada to complete the survey. The subset of responses that received the highest level of agreement (or disagreement) amongst the women are shown in Table 1 below.

Clearly, most of the athletes consider biological sex to be more important than gender identity in eligibility criteria for high-performance sport categories. They feel they have not been consulted, that their voices are often dismissed, and that they are unable to speak about this policy area without being called transphobic. They voice considerable sadness, distress, frustration, fear, and anger as a consequence of “speaking up” (Devine and Howe 2022, 66).

What about “transmen” and “non-binary” female athletes?

One of the important topics that emerged in this report is the plight of trans-identifying female athletes (“transmen”) and female non-binary athletes. Some of the survey respondents voiced concern that transmen have been overlooked in this policy debate:

All of them felt that transmen would have no chance of being competitive in male categories and some expressed concern and empathy for transmen competing in male categories from both a safety and fairness perspective. Most of the athletes had no problem whatsoever with transmen who were not taking exogenous testosterone remaining in female categories given this aligned with the same sex eligibility logic expressed by most of them. (Devine and Howe 2022, 56)

The authors conclude from this statement that the opinions expressed in this survey are not indicative of “transphobia” (transmen, after all, are also “trans”), but, rather, have to do with valid concerns about fairness and a level playing field.

Conclusion

Devine and Howe’s conclusion is powerful and hard-hitting, to say the least:

The silencing of female athletes is a serious ethical, legal, and human rights problem for sport internationally, including, it seems, in Canada. It contravenes fundamental freedom 2a of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the “freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression” which is “guaranteed equally to both sexes” and “guaranteed equally to male and female persons.” (2022, 73)

Addressing the organization most responsible for the undermining of female athletes’ rights in Canada, the authors go on to assert:

The CCES transgender guidelines… echoed throughout the Canadian sport infrastructure, might therefore be considered to constitute institutional discrimination against the female athletes on the basis of sex. (Devine and Howe 2022, 79)

While Canadian NSOs might have felt pressured into establishing scientifically unfounded and entirely unsporting inclusion policies due both to incessant prodding by trans advocates within the CCES and the fear of being found guilty of Bill C-16 violations, there was no need to impose such a draconian policy upon hapless Canadian female athletes. The authors rightly point out that “inclusion of transwomen athletes does not have to be in female categories” (Devine and Howe 2022, 81). There are alternatives that involve making additional categories or having the men’s category be deemed as “open” (Pike, Hilton, and Howe 2021, 32) to athletes of all identities. Under such a dispensation, no athlete brings to their new category an unfair competitive advantage.

It’s important to note that never did a female respondent to Devine and Howe’s survey suggest that transgender athletes don’t belong in Canadian sport. The argument has never been about “excluding transgender persons.” Rather it is about accommodating everyone in a manner that is fair, safe, and respectful.

Recommendations

This survey of the views and insights provided by 25 high-performance female athletes in Canada has exposed the immense unfairness and potential harm created by senseless CCES policy recommendations on transgender inclusion. (See the Appendix for a note about sample size.) Dutiful compliance by NSOs has resulted in a bizarre manifestation of sex discrimination that is both painful and difficult to understand.

And what has been written in Devine and Howe’s ground-breaking report is not even the worst of it. The authors mention that a second report provided to Sport Canada has been redacted because things revealed in some of the interviews are too sensitive to be made public.

Should Canadians be unhappy with the current policies on transgender inclusion in sport? Yes. Should they be putting the case for change to federal and provincial governments and sporting authorities? Absolutely.

Fairness and safety for female athletes in Canada are not beyond reclamation.

Sport Canada should:

- formally withdraw the CCES transgender guidelines,

- overhaul the CCES and ensure that it gets back to focusing on its original mandate, and

- undertake a broad consultation process to create new guidelines for a fair and balanced accommodation of both biological sex and gender identity in Canadian sports.

Anyone seeking a resolution to the conflict that currently exists between sex-based (human) rights enshrined in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the (human) rights to “gender expression” and “gender identity” set out in Bill C-16 should know that such a resolution is entirely possible.

When Bill C-16 was introduced in Parliament on November 18, 2016, MPs on both sides of the House pointed out that there was a difference between biological sex and gender identity (Canada, House of Commons 2016). Indeed, this difference manifests itself in sports, in prisons, in medicine, and in many other contexts. Clearly, as the sports policy debacle has shown, there are fields where sex-based rights remain important and indeed must take precedence. Since the passage of Bill C-16, however, our political leaders seem to have forgotten what they so clearly knew when Bill C-16 was being debated.

Perhaps it is time for the Parliament of Canada to take a page from the UK Equality Act and amend Bill C-16 to include appropriate sex-based exemptions (United Kingdom 2010) that will ensure women in Canada can enjoy the same fairness, safety, and privacy as their male counterparts, not only in sports but in all walks of life. Anything else would be unworthy of the just society we claim to value so highly.

About the author

Linda Blade, a former Canadian track and field champion and NCAA All American, has spent 25 years as a sport-performance professional coach in Edmonton in over 15 sports. Linda has worked with NHL players, Olympics athletes and Athletics Canada’s Run-Jump-Throw program. Linda has a PhD in Kinesiology, and she’s travelled the globe conducting coach education courses on behalf of World Athletics, including a groundbreaking course for female coaches in Iran in 1995. In 2014, she was elected as president of the board for Athletics Alberta, where she works diligently to review and contribute to Canadian sport policy.

References

Athlete Ally. 2022. “Athlete Ally, 200+ Scholars and Athletes Condemn Sport Canada’s Funding of Anti-Trans Research.” Athlete Ally. Available at https://www.athleteally.org/scholars-athletes-condemn-sport-canadas-funding-of-anti-trans-research/.

Blade, Linda, with Barbara Kay. 2020. Unsporting: How Trans Activism and Science Denial Are Destroying Sport. Rebel News Network.

Canada, House of Commons. 2016. “42nd Parliament, 1st session, Friday, November 18, Number 110.” House of Commons Debates. House of Commons of Canada. Available at https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/42-1/house/sitting-110/hansard.

Canada. 2016. Bill C-16: An Act to amend the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Criminal Code. Tabled in the House of Commons, October 18. Government of Canada. Available at https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/pl/identity-identite/statement-enonce.html.

Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport [CCES]. 2016. Creating Inclusive Environments for Trans Participants in Canadian Sport: Guidance for Sport Organizations. CCES, May 4. Available at https://cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/cces-transinclusionpolicyguidance-e.pdf.

Canadian Powerlifting Union. 2019. CPU Bylaws, Policies and Procedures. Canadian Powerlifting Union. Available at https://www.powerlifting.ca/constitution.html.

Canadian Press. 2022. “Sport Canada to Stop Survey After Complaints of Discrimination Against Transgender Athletes.” Global News (May 9). Available at https://globalnews.ca/news/8822169/sport-canada-survey-transgender-athletes/.

Devine, Cathy, and Leslie A. Howe. 2022. Canadian High-Performance Female Athletes’ Voices: Transgender Inclusion in Elite and Olympic Sport Guidelines. Project Report. Sports Canada. Received from Sport Canada on January 24, 2023 via an Access to Information and Privacy request. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Canadian-High-Performance_Female_Athletes_Voices-Project_Report-compressed.pdf.

Keys, Marc. 2022. “Elite Strength Sports (IPF and IWF) a Comparision of Sex and Performance.” Cast Iron Strength (May 2). Available at https://www.castironstrength.com/elite-strength-sports-ipf-and-iwf-a-comparision-of-sex-and-performance/.

International Powerlifting Federation [IPF]. 2022. IPF Policy Statement for Transgender Athletes. IPF. Available at https://www.powerlifting.sport/fileadmin/ipf/data/rules/IPF_Transgender_Policy_FInal.pdf.

Montague, James. 2012. “Hero or Villain? Ben Johnson and the Dirtiest Race in History.” CNN (July 23). Available at https://www.cnn.com/2012/07/23/sport/olympics-2012-ben-johnson-seoul-1988-dirtiest-race/index.html.

Nequals8. 2022. Web site home page. Nequals8. Available at https://nequals8.com/.

Pike, John, Emma Hilton, and Leslie A. Howe. 2021. Faster, Higher, Stronger: The Biological and Ethical Challenges to Including Transgender Athletes in Women’s Sports. Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Dec2021_Faster_higher_stronger_Pike_Hilton_Howe_PAPER_FWeb.pdf.

Rugby Canada. 2019. Trans Inclusion Policy. Rugby Canada (January 1). Available at https://rugby.ca/uploads/Documents/TransInclusionPolicyEN_DEV_POL_20190101_FINAL.pdf.

Trans Inclusion in Sport Expert Working Group. 2016. Creating Inclusive Environments for Trans Participants in Canadian Sport: Guidance for Sport Organizations. Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport. Available at https://cces.ca/sites/default/files/content/docs/pdf/cces-transinclusionpolicyguidance-e.pdf.

United Kingdom. 2010. “Part 7: Separate and Single Services. Separate Services for the Sexes: Paragraph 26.” Equality Act 2010. Government of the United Kingdom. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/notes/division/3/16/20/7.

World Rugby. 2021a. Transgender Guidelines. World Rugby. Available at https://www.world.rugby/the-game/player-welfare/guidelines/transgender.

World Rugby. 2021b. Transgender Women Guidelines. World Rugby. Available at https://www.world.rugby/the-game/player-welfare/guidelines/transgender/women.

Appendix: A note on sample size

Some readers might consider the Devine and Howe sample size (N=25) for a nation-wide survey to be small. The authors make no apologies; they see this study as a preliminary inquiry that demonstrates the need for a more thorough consultation of female athletes by Canadian sports organizations. It is noteworthy, however, that the sample would have been larger but for an unanticipated intervention. In the second month of the survey, one of the participants leaked it to US-based trans advocacy group, Athlete Ally. This American organization immediately drafted a letter, signed by over 200 scholars and athletes, demanding that the Canadian government immediately stop the survey (Athlete Ally 2022). Sport Canada complied (Canadian Press 2022) and funding for the project was instantly stopped.

By that time, 25 respondents had already completed the survey, which enabled the report to be produced. It is also worth stating that this sample size of 25 is considerably larger than the most famous survey of eight trans-identifying male athletes (N=8) that the International Olympic Committee used to change eligibility rules in 2015; changes that indisputably harmed every female athlete around the world (Nequals8 2022). All it took was a survey of eight male-born athletes for the IOC to impose a policy that was unfair to female Olympians worldwide.

Given that the Canadian cohort is a representative subset of the global number of female athletes, a survey of 25 of them should be seen as a firm foundation for arguing that there is a serious problem with the current policy and that female athletes’ views have not been given their due weight on an issue of vital importance to their rights and interests.