By Raheel Raza and Mohammad Rizwan, October 9, 2024

It’s been one year since the war in Gaza started, following a bloody terrorist attack and hostage-taking by Hamas. Few expected the world would mark the first anniversary of the attacks with a war on the verge of escalation.

The recent cyber-attack on Hezbollah’s communication system in Lebanon clearly indicates the Israeli military operation is moving north to clear up the terrorist networks supported by Hezbollah in southern Lebanon.

This makes sense because dismantling merely one terrorist entity will not solve the problem. Without cleaning up the ecosystem of Iranian terrorist tentacles in Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Gaza and Yemen, it would be tantamount to resetting the status quo, rendering everything that’s taken place since October 7 meaningless.

The world and the Middle East find themselves at a juncture where they must find a solution for permanent peace. This can be achieved by first eliminating terror proxies, and neutralizing their puppet master Iran, and then moving on to resolve the Palestinian question, which could ultimately give hope and a future to a large Palestinian population living in Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan and elsewhere.

Many political pundits have offered solutions for perhaps the most contentious and complicated political questions since the Second World War. But let’s try to find out where the popular two-state solution stands on October 7.

Let’s remember, no solution is good enough until you take terror and its sponsors out of the equation. This must be left to military and national security strategists, as terrorists cannot be negotiated with, as they have proven time and time again.

Is the two-state solution good enough today to underwrite permanent peace in the Middle East? Is it still as relevant as it was in 1991, 2000 or 2007?

If it is, there should have been peace since 2007 because the establishment of self-government in Gaza and the West Bank constitutes the first step toward a proposed two-state solution that the world has now pursued.

Gaza was given autonomy and substantial development aid to build its own civilian institutions. In a spirit of co-existence, Israel opened its doors to workers from Gaza who crossed over to work and returned for the night. All this was pretty much on the lines of a fancied and proposed two-state solution.

But it failed spectacularly.

Similarly, in the West Bank, the Mahmoud Abbas administration was given significant aid and was largely left in peace and on its own. What happened there? They got a notoriously corrupt administration that did little for its population both politically and economically.

So, both the political autonomy and economic empowerment parts that were key components of a two-state solution unravelled and, in the case of Gaza, actually backfired.

Another attempt to build a new Gaza or a new West Bank would likely end up no different than the previous one. There is no evidence to suggest otherwise. If one takes Iran’s terrorist support out of the equation (assuming terrorism would be eliminated militarily, which so far has proven impossible since 9/11), even then the new autonomous Gaza and West Bank have every chance of sliding into corruption-infested ghettos.

We are unsure what two-state solution the world talks about after witnessing a bloody end to the first phase of an original two-state solution.

Abraham Accords? Very good idea. But all accords, treaties, manifestoes, constitutions, charters depend on the sweet will of the parties, don’t they? This has been notably absent, on the part of key agitators.

A peaceful solution to the Palestinian question narrows down to a seemingly simple one-liner. The new-post-Hamas generation of Palestinians who have seen what opposite to peace could mean, must accept and acknowledge that Israel has a right to exist as a state and Jews are not the enemy.

This fundamental change in the thinking process is a prerequisite before we even start talking about the next chapter in the Middle East.

Two factors would weigh heavy in any future peace calculations. The Iranian regime has to realize (through whatever means necessary) that its policy of projecting terror through proxies is detrimental to its political interests both at home and abroad. Iran must be made to see that projecting terror through proxies is expensive, bloody, fruitless and would cause the downfall of a repressive system the regime has built to prop itself up at home.

The collapse of the Iranian regime could trigger a collapse of its terror proxies and that in turn could create the conditions where a Palestinian or Arab supporter could change its mind about Israel and Jews.

And this is where the Abraham Accords would help.

A web of economically empowered local government networks in the Palestinian areas of the West Bank and Gaza, overseen and protected by a consortium of Arab states, could provide a platform to build a future state.

Taking Iran and its proxies out of the equation would not guarantee that this still politically active Palestinian question would not get another ambitious sponsor from countries that may see it as another balance tilt towards the West and American interests. But a reformed Saudia Arabia, a progressive UAE and other states that are or would become part of Abraham Accords could play an oversight role.

A peaceful and progressive Middle East would have the potential of keeping South Asia and the Indo-Pacific calm, offering new trade and investment opportunities for Canada.

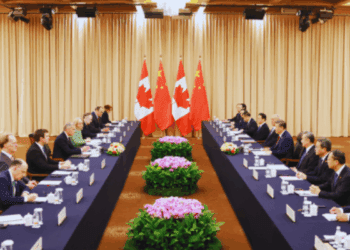

We have already witnessed in anguish what a violent and turbulent Middle East does to streets in Canada. A pro-active future role by Canada in the Middle East and South and Central Asia would not go to waste.

Raheel Raza is a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Rizwan Mohammad is a senior member of The Council for Muslims Against Antisemitism.