By Tom Keating and Robert W. Murray, March 4, 2024

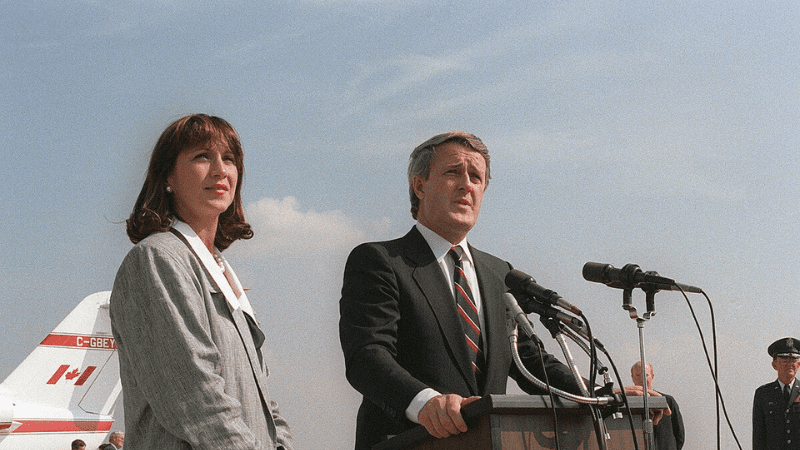

The passing of former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney leaves a timely reminder of the role that Canada once played on the international stage, and the creativity and influence that effective leadership can have on Canada’s ability to move the international agenda.

Much of the attention on the former prime minister’s legacy has rightly focused on his government’s economic policy, including the Goods and Services Tax and, most notably, his ability to conclude a comprehensive free trade agreement with the United States.

While widely castigated at the time, both policies have been critically important in steering the Canadian economy through the vagaries of economic crises and dramatic shifts in US foreign trade policy, and in improving Canada’s overall global economic competitiveness. They also served to provide some stability in government revenues amid the fervent anti-taxation movement that has grown as rapidly as the demand for better government services.

A less commonly noted but important contribution was Mulroney’s successful effort to advance a human rights agenda that radically reformed Canadian foreign policy and had wide-ranging repercussions for many international organizations, including the United Nations and the Commonwealth.

As Canada’s prime minister during the dramatic and rapid end of the Cold War and the collapse of the former Soviet Union, Mulroney’s government responded with an aggressive, yet diplomatically sensitive effort to enshrine liberal democratic principles in the international arena. Canada’s presence in multilateral institutions such as the Commonwealth, the Organization of American States, and the UN helped to entrench these principles – and by extension Canadian values and national interests – in institutional charters that served both global and Canadian interests.

More significantly, they also prescribed the legitimacy of intervention in countries where such principles were at risk. A very important component of such interventions was the need for legal and institutional support, hence the willingness to work through established organizations despite the restraints such organizations might impose.

These institutional reforms were complemented by diplomacy in specific areas of Canadian interest or that Mulroney felt were worthy of Canada’s political, economic, military, or moral involvement: he directly challenged British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher by siding with the majority of Commonwealth members to sanction South Africa for its racist apartheid system; he helped to convince US President George H.W. Bush to work through the UN to respond to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait; and, along with other governments, he convinced the UN to intervene in the civil war raging in the former Yugoslavia – both in the name of international security and human rights.

The effectiveness of these measures, while checkered for some, did mark a concerted effort to take advantage of the opening provided by the end of the Cold War to construct a more robust international security and human rights regime – and to do so through institutions that would allow not only for the widest possible consensus but also for Canada to play a crucial role in global affairs by leveraging its multilateral relationships.

Mulroney’s initiatives laid the groundwork for what would eventually become the human security initiative that was advanced under the succeeding Liberal government’s foreign minister, Lloyd Axworthy. This agenda contributed to the conclusion of the anti-personnel landmines ban enshrined in the Ottawa Treaty and the establishment of the International Criminal Court. The longevity of these policies has been sorely tested in the ensuing years yet continue to have enduring power.

Mulroney seemed to understand that working through the established international and regional multilateral institutions provided these policies with the political and legal legitimacy required to maintain other countries’ support. He further understood that these institutions provided important forums through which Canada could greatly impact the global political agenda, project Canada’s national interests and values, and protect Canada’s national security. This multilateral tradition is an important historical hallmark of Canada’s foreign policy.

At a time when the international community is sorely in need of the sort of initiatives and diplomacy that Mulroney brought to the international stage, much can be learned from the intentional and strategic approach he took to advancing Canada’s foreign policy. Mulroney knew that Canada had the capability and opportunity to play an important leadership role in global affairs both at the end of the Cold War and after. As the international system continues to evolve, it is past time for Canada to re-embrace its place in global affairs and to contribute meaningfully to international peace and security.

Tom Keating is Professor Emeritus at the University of Alberta.

Robert W. Murray is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald Laurier Institute.