By Nigel Rawson and John Adams, November 23, 2022

For seven years, the Patented Medicines Prices Review Board (PMPRB) – the federal government’s tribunal that ensures patents for new medicines are not abused by drug developers – has pushed for new powers to drastically reduce drug prices in Canada. After courts struck down most of these powers and rogue interpretations of its old rules, the Liberals announced that only the change in comparison countries would be implemented.

In October, the PMPRB took another kick at the can, publishing draft guidelines for consultation until December 5th. These cast a large shadow of uncertainty over patient access to new therapies and make it virtually impossible for global enterprises to predict what they can charge for new drugs here.

The Liberals talk about encouraging innovation. But do they walk the walk? Will they intervene to stop the PMPRB trying to do through the backdoor of its guidelines, what courts have said cannot be done through the front door of unconstitutional regulations?

PMPRB plans

The PMPRB has released webinars intended to provide further information on its latest proposed guidelines. They reveal the Board has invented complicated ways, never contemplated before, to further its objective of severely reducing drug prices. The policy question for federal Health Minister Jean-Yves Duclos is: does Ottawa still want to drive down the price of new drugs by regulation, not negotiation, as drastically as before?

The PMPRB has decided to take this approach instead of simply using the price reference test that it has done since its establishment in 1987 with the new comparator countries. As the PMPRB executive director said at the webinar for the public, the PMPRB has been on a “modernization track” for some time and not to change would waste “the toil and trouble over the last seven years.” This is a poor reason for a policy change that will deny or delay access to innovative medicines for many Canadians.

That being said, what does the PMPRB intend to do?

Unlike the 2017 proposed guidelines in which the plan was overtly laid out, the 2022 version is short on detail and long on obfuscation. Nevertheless, it is clear the PMPRB intends to take the potentially more threatening approach of starting an investigation by PMPRB staff if a manufacturer’s list price isn’t considered low enough, although what will lead to an investigation is much less clear. The guidelines are more about criteria that could lead to an investigation.

The PMPRB divides medicines into “existing” and “new.” Existing medicines are all those with regulatory approval before July 1, 2022, and all medicines with an authorized sale under Health Canada’s Special Access Program. Everything else is a new medicine.

Criteria that could lead to a staff investigation for all medicines are: a complaint is received with regard to the pricing of the medicine; the list price increased by more than the changes in the Consumer Price Index (CPI); or no international prices were filed by the patentee. An additional criterion for an existing medicine is that its list price exceeds the highest list price in the 11 comparator countries. For a new medicine, an investigation may be triggered if its list price:

- Exceeds the median list price in the comparator countries.

- Falls between the median price in the comparator countries and the lowest price in those countries, but exceeds the top Canadian price of therapeutic class comparator drugs.

- Exceeds the midpoint between the top Canadian price of therapeutic class comparator drugs and the lowest price in the comparator countries, and the top Canadian price of therapeutic class comparator drugs is more than 50 percent lower than the medicine’s lowest list price in the comparator countries.

The policy question is: what do any of these triggers for staff investigations have to do with the legal mandate of PMPRB to protect Canadians from excessive prices stemming from patent abuse?

What’s clear from the proposed guidelines?

First, a complaint could come from anyone – individuals, organizations with ties to anti-biopharmaceutical industry activists, businesses in competition with a patentee, or governments – and could be frivolous, reasonable or malicious. Which will lead to an investigation?

Second, the degree of clinical improvement, part of the PMPRB’s process used for 35 years to reward innovative developers with a higher price, will no longer be an integral part of each assessment. The implication is that the PMPRB will regard novel therapeutic advances that extend and/or improve the quality of lives the same as medicines for minor ailments. Why is the PMPRB proposing to eliminate the role of an advisory committee in determining the level of therapeutic improvement?

Third, regular reassessments can be imposed and prices will be benchmarked annually. In addition, the PMPRB may change what warrants investigation any or every year. Therefore, drug developers will have to consider whether their medicine’s price will be compliant at launch, as now, and over its patent life.

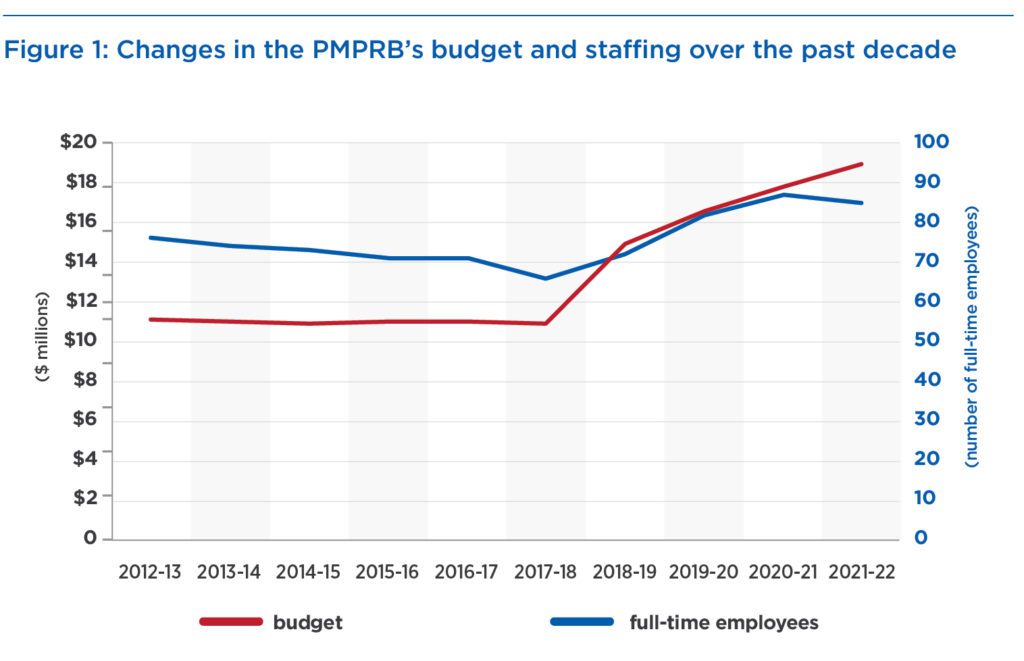

Fourth, no effort has been made, despite budget and staffing increases of 72 percent and 30 percent over the past five years (Figure 1), to assess the potential impact the changes will have on drug prices and patient access to medicines. PMPRB staff side-stepped this issue by referring to their Guideline Monitoring and Evaluation Plan as a way of assessing the impact. But this is a self-monitoring scheme without credible or independent oversight.

What’s less clear about the proposed guidelines?

It is unclear as to whether any medicine satisfying the new cumbersome criteria would automatically be the subject of an investigation or only some will be. Because the PMPRB will take a case-by-case approach and hasn’t proposed any overt price tests, developers have no way of assessing whether their price will actually trigger an investigation. This will continue the uncertainty about medicine prices in Canada that has existed over the past five to seven years, which has resulted in fewer clinical trials and other research studies being performed and fewer new medicines being submitted for regulatory approval here.

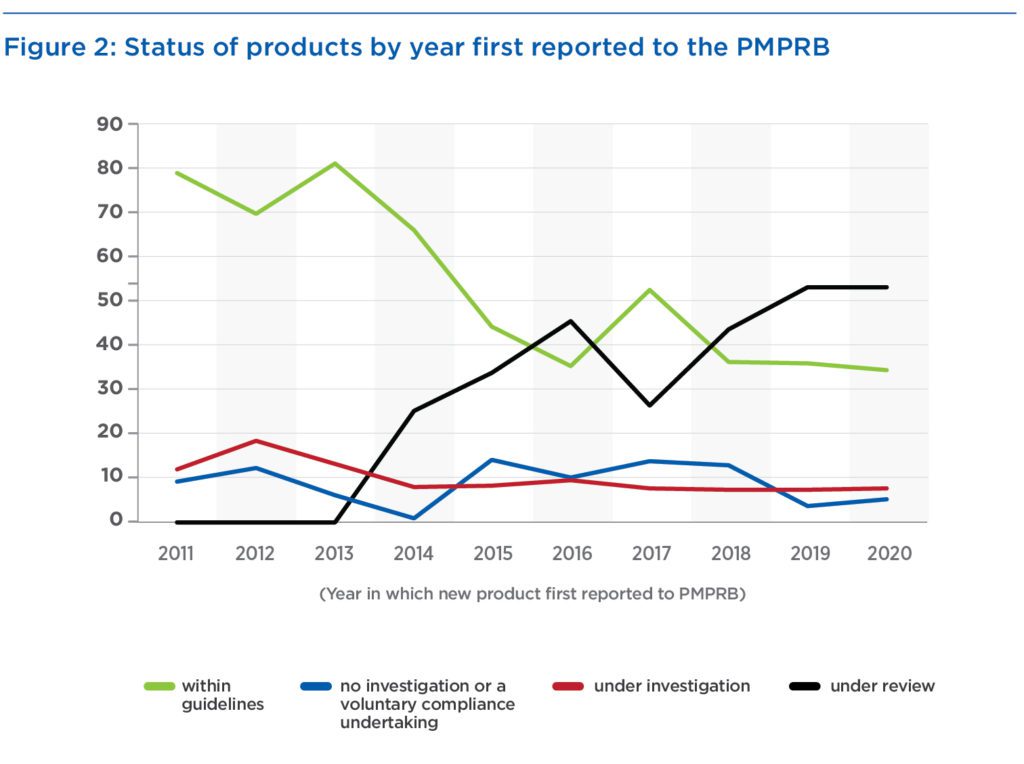

Despite its increase in budget and staffing, how many investigations the PMPRB could perform at any one time is unknown. Over the past decade, the average number of investigations has been less than 10 – an average that decreased to fewer than eight over the period of increasing staff and budget. Products under investigation by year in which the product was first reported to the PMPRB constitute only 7 to 18 percent (Figure 2). However, the percentage of products “under review” has increased dramatically from 0 to 53 percent. The inclusion of these products gives the impression that the percentage of products within guidelines has fallen, but excluding products under review shows a stable percentage of 70 percent of medicines being within guidelines during the past five years.

Conclusion

Conclusion

The PMPRB persists in its belief that forcing lower prices will not affect developers’ decisions about whether or when to bring medicines to Canada. The PMPRB’s executive director repeated his long-standing and unsupported claim in the public’s webinar that, if drug developers can sell medicines at a lower price in comparable countries, they can do the same in Canada. This is deliberate misdirection. The carrot of negotiations, not the stick of regulations, achieve the prices in other countries.

The PMPRB continues to work towards an objective of “low” or “reasonable” prices. This flouts a Federal Court of Appeal’s unanimous decision that “excessive pricing provisions in the Patent Act are directed at controlling patent abuse, not reasonable pricing, price-regulation or consumer protection at large.” Other courts have ruled that the PMPRB is not empowered to lower prices without evidence of excessive pricing.

Patents are intended to reward inventors of new therapies with market exclusivity for a fixed period, allowing a premium price to recoup their investments. The trade-off: patentees disclose details of their inventions for anyone to access and be able to launch competing versions immediately after patent expiry.

Canada allows a 20-year patent term for new medicines, but research and regulatory approval usually consume the first half, so that effective market exclusivity is commonly only eight to 10 years. If PMPRB revisions deny developers the opportunity to recoup their investment and make a profit during this short period, they will decide Canada is not a worthwhile market.

These latest guidelines are not fit for purpose. They increase the risk of adding more uncertainty around drug prices and, thus, reduced or delayed access to new treatments. They continue the PMPRB’s obsessive anti-biopharmaceutical industry bias in the name of doing the bidding of the federal government. The new guidelines would also eliminate the role of an independent advisory committee in determining how much a new drug improves patient outcomes – a big improvement would justify a higher price, for example. The result will be to a further decline in biopharmaceutical innovation, research and manufacturing in Canada and extend suffering already experienced by Canadians with unmet medical needs. As commentator Neil Palmer wrote, “The PMPRB has demonstrated little or no interest in patient health or health outcomes. It is time that changed.”

If the Liberals truly want to encourage biopharmaceutical innovation in Canada, they need to slap down the PMPRB’s bias and hostility towards the biopharmaceutical industry and begin a collaborative and constructive dialogue with the industry that balances pricing and access to new medicines for Canadians with unmet health needs. The voices of patients must be included in that dialogue.

Over to you, Minister Duclos.

Nigel Rawson is an affiliate scholar with the Canadian Health Policy Institute and a senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, as is John Adams, co-founder and CEO of Canadian PKU and Allied Disorders Inc.