This article first appeared in the National Post.

By Heather Exner-Pirot and Robert W. Murray, September 20, 2022

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg made a visit to Canada last month in what must be seen as an effort to prod us into taking our Arctic security more seriously. What has changed since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, and how should Canada respond?

Beginning with Mikhail Gorbachev’s famous 1987 Murmansk speech calling for the Arctic to become a “zone of peace,” the region was marked by low conflict and high stability for 35 years. His passing last month coincided with the end of this era.

The Arctic Council, encompassing the eight nations with territory in the Arctic Circle as well as representatives from Indigenous groups, epitomized the good, constructive relations that were possible between Russia and the West. It also reflected an emerging multilateral regime for the Arctic that could have led to beneficial collective outcomes. But the council’s work, and the relative stability of the Arctic, are now on pause, indefinitely.

The Arctic Council explicitly prohibited discussions on military security, and for years there was debate as to whether some parallel forum was needed to address security issues. With Finland and Sweden joining Norway, Canada, Iceland, Denmark and the United States in the alliance, the debate must be considered closed: NATO is that parallel forum.

Canada has long been reluctant to see NATO play a larger role in the Arctic region. Part of this was apprehension that more international activity would erode Canada’s de jure and de facto sovereignty in the area. But mostly it was a rational calculation that bolstering NATO’s presence in the Arctic would needlessly provoke Russia and upset the delicate but mutually beneficial balance that kept the region stable.

For many years, that meant keeping a low profile for NATO in the region. But Russia has taken steps which make that posture untenable. The focus must now shift to deterrence, and allies must determine how NATO can play a role in Arctic security. For Canada, that means bolstering our presence, investment and leadership in NATO’s northern flank, and taking a more proactive role in protecting our national security.

But first we need to understand what the security risks in the region are. Canadian governments have often been politically reactive rather than strategic in their Arctic defence planning. It is not enough to periodically announce billions in new spending to counter vague threats to Arctic sovereignty, or to look tough on Russia and China. Spending must match needs and must be commensurate with risks.

There never was a serious race for resources in the region, and prognostications of how climate change will open up the region appear to be overblown. The Arctic remains a difficult and expensive region to navigate in and extract resources from. In many ways, climate changes make it harder, not easier, to operate in the Arctic as ice patterns change, weather gets more unpredictable, and permafrost melts.

But there are two areas in the Arctic that do have heightened security risk. One is in Fennoscandia. With Finland and Sweden joining the alliance, NATO’s physical border with Russia will become approximately three times longer than it was before the Ukraine-Russia War, straddling northern Norway, Finland and the Baltic states.

Canada has experience and expertise operating in northern conditions, and already leads a NATO battlegroup in Latvia. It can contribute in practical ways to the defence of this region. The likelihood of a Russian incursion into northern Europe is many times greater than some conquest of Ellesmere Island or other part of the Arctic archipelago, and our efforts and investments must account for this.

The second is nuclear deterrence. Nuclear war with Russia is still a very remote possibility, but it is undoubtedly more of a threat than it was a year ago. The shortest path to North America for Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles and bombers is over the Arctic Circle. This makes Norad (the North American Aerospace Defence Command) important not only for continental defence, but for the United States’ global nuclear deterrence capability as well.

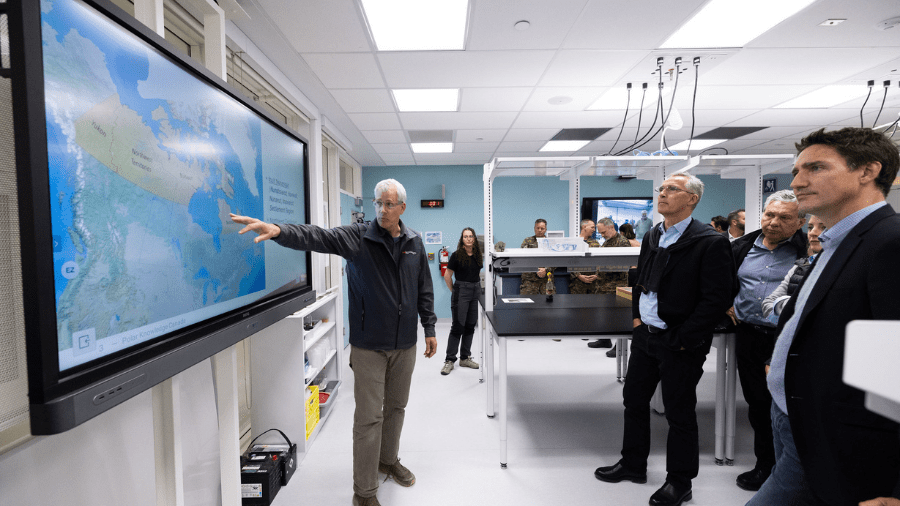

It is no coincidence that Defence Minister Anita Anand in June announced multibillion-dollar upgrades to Norad, and that Stoltenberg’s trip to the Canadian North focused on visits to a radar station in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, and an air force base in Cold Lake, Alta.

Russia has shown that its interests and strategies will not be limited by tough talk or rhetoric. It is time that Canada and other NATO states demonstrate a commitment to Arctic security that forces Vladimir Putin to think twice about further disrupting the region’s relative stability.

Heather Exner-Pirot and Robert W. Murray are both Senior Fellows at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.