Afghanistan illustrates what can result if democratic governance, however imperfect, is replaced by intolerance and violence against fellow citizens, writes David Kilgour.

Afghanistan illustrates what can result if democratic governance, however imperfect, is replaced by intolerance and violence against fellow citizens, writes David Kilgour.

By David Kilgour, September 20, 2021

With democrats everywhere grieving over recent events in Afghanistan and the 20th anniversary of 9/11, it is worth recalling that as the first plane struck the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001, all 35 Organization of American States (OAS) member governments were in Peru signing a democratic charter that denied OAS membership to any dictatorship. As a member of the Canadian delegation to Lima, I recall the sense of great pride in making such an advancement for the cause of democracy and freedom, quickly shattered by a terrible blow for tyranny struck by the 9/11 plotters.

And even as we mourn the fall of Afghanistan into darkness under the Taliban again 20 years later, we should remember that the two decades since the OAS stood up for democracy has seen significant advancements for the democratic cause. While there have been serious setbacks, if the community of nations can commit itself to freedom and the rule of law around the world, millions more can benefit from democracy.

Democratic governance has expanded across much of the world since the 1970s. In 1977, only 35 of 143 nations with a population of at least 500,000 qualified as democratic according to the Center for Systemic Peace’s Polity Project. By 2017, 96 of 167 countries were deemed democratic; only 21 remained unreformed autocracies. Democratization has unfolded in a myriad of narratives. I’ll take three examples.

In 2004, for example, 80 percent of Afghans risked their lives to vote in their first presidential election. One was Dr. Sima Samar, later deputy president in the Afghan Transition Team but afterwards compelled to resign for questioning religious laws. She lobbied for democracy as chair of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission and UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Sudan. Samar has dedicated her life to women’s empowerment.

The now controversial Aung San Suu Kyi spent almost 18 years under house arrest in Myanmar/Burma. In 1990, her National League for Democracy (NLD) party won the majority of election votes but weren’t allowed to take their seats. On February 1, 2021, the military staged a coup following the NLD’s landslide election victory. The world is horrified that the generals have killed over 1000 protesters to date, including children.

The late Václav Havel, the Czech dissident whose dissections of totalitarian rule helped ultimately lead to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, was asked about his country’s newfound freedom. He responded: “From where did [Czechoslovakia’s] young people . . . take their desire for truth, their love of free thought, their political ideas, their civic courage…?” The answer lies in the human desire everywhere to choose the types of societies we want to build for ourselves – ones grounded on values of human dignity for all and the rule of law.

In addition to the action taken by the OAS against dictatorships 20 years ago, multilateral bodies have had an important role to play in spreading democracy.

In the 54-nation Commonwealth, shared governance values were reflected in the Harare Declaration of 1991, when governments pledged their commitment to the protection and promotion of the Commonwealth’s democratic political values and rule of law. Members in good standing must have civilian, democratically elected governments.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) enhances democracy from “Vancouver to Vladivostok” through monitoring democratic processes among 57 participating states.

La Francophonie comprises 88 member governments and observers that share French as a common language. It represents 300 million Francophones on five continents. Canada has worked with it to support democracy, undertaking several informal political initiatives in countries at risk.

Representative democracy is indispensable for a peaceful, prosperous world with equal opportunity for all, although the roads to open democratic societies are challenging. With the economic crisis arising now from COVID-19, democracies face both enormous pressures and new opportunities. This turmoil tests our commitment to democratic principles and best governance practices.

Democracy works in tandem with the spread of the rule of law and the enhancement of human dignity. International institutions must accord incrementally more weight to human rights, the rule of law, and multi-party democracy. We must safeguard and enhance our democratic practices and help to strengthen democracies abroad, remembering always that it begins with each of us as individual citizens.

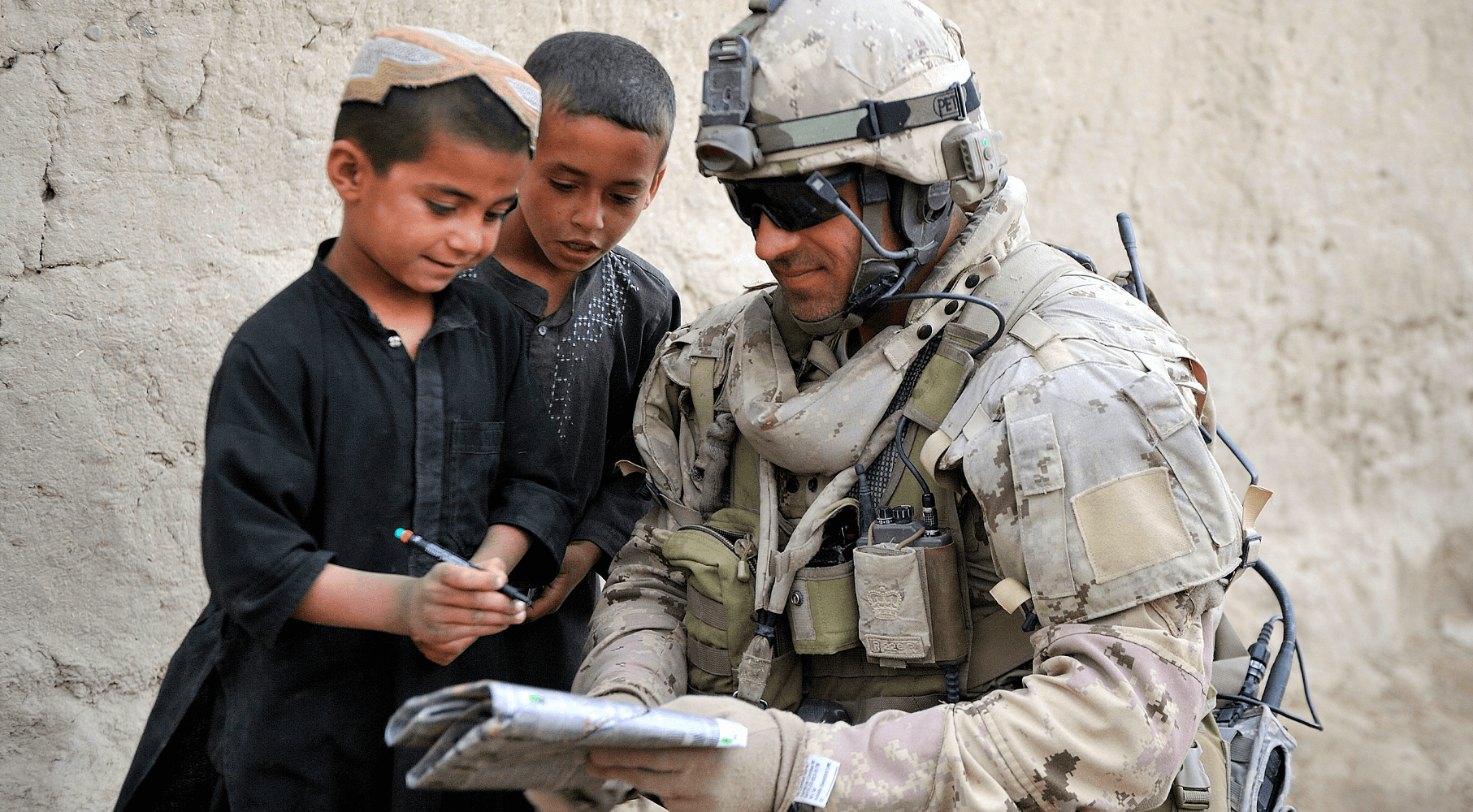

In Afghanistan, the 20-year struggle to build democracy faced many significant failures. Its present situation illustrates what can result if democratic governance, however imperfect, is replaced by intolerance and violence against fellow citizens.

David Kilgour is a Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and the former Secretary of State (Asia-Pacific) from 2002 to 2003.