The world must figure out how to balance the free flow of digital data and information, which relies on speed and uninhibited pathways, and the imperative to protect intellectual property and national security concerns for states, write J. Berkshire Miller and Brian Lee Crowley.

The world must figure out how to balance the free flow of digital data and information, which relies on speed and uninhibited pathways, and the imperative to protect intellectual property and national security concerns for states, write J. Berkshire Miller and Brian Lee Crowley.

By J. Berkshire Miller and Brian Lee Crowley, April 26, 2019

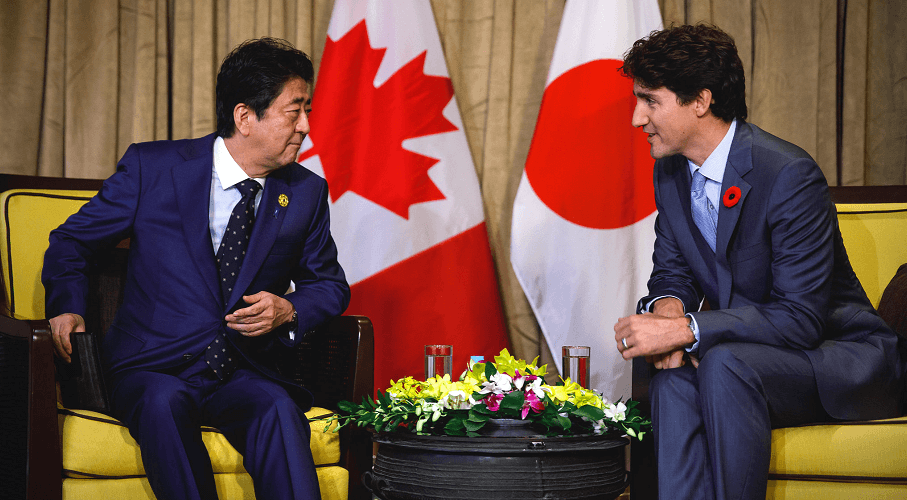

Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, will visit Canada this weekend for a summit with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau ahead of the upcoming G20 Summit in June. The visit comes at the conclusion of a large international tour for Abe, who has made stops to France, Italy, Slovakia, Belgium, and the United States, before landing in Ottawa. It also comes at a critical juncture for Japan as it prepares to host the summit for the first time.

His trip is focused on ensuring that the summit in Osaka is set up for success, amidst rising concerns of protectionism, as well as lingering apprehensions regarding the future of Brexit and trade tensions between the U.S, and China.

High on Abe’s agenda during his G20 chairmanship is the promotion of a global-data governance regime, which will likely be at the centre of his talks with the prime minister. After decades of loose and unenforced rules in cyberspace, Japan has begun to lead the charge for a multilateral commitment to fair, open, secure, and transparent data governance under the World Trade Organization.

The stakes here are immense. The world must figure out how to balance the free flow of digital data and information, which relies on speed and uninhibited pathways, and the imperative to protect intellectual property and national security concerns for states.

In his speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos earlier this year, Abe stressed that, “each day 2.5 quintillion bytes of data [are] created,” without anyone really knowing what the international rules are governing the creation, transmission, security, and control of those data. In this vacuum, different countries are responding to the surge of digital data in different ways.

Authoritarian regimes in China and Russia, for example, have placed an extraordinarily large number of barriers to the entry of data and have passed draconian laws aimed at ensuring that control over data transiting their networks remains almost entirely in the hands of domestic security and intelligence authorities. Beijing and Moscow are therefore able to exploit a lack of global consensus on digital data governance to serve their own national interests. Walling themselves off and controlling data serves two purposes: providing a protectionist advantage to domestic firms and maintaining a firm control on data for national security purposes.

Even worse, this heavy-handed and protectionist approach is spreading. Vietnam, for example, is a communist state but with a surging and increasingly market-oriented economy. Hanoi joined the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which unites 11 nations – including Japan and Canada—in a massive multilateral trading bloc representing nearly half a billion people and almost 15 per cent of global GDP. But in the absence of international data rules, Hanoi has also been moving to turn off the taps on data, passing strict cybersecurity laws and pressing social media giants—such as Google and Facebook—to transmit data if requested by government.

Ensuring a commitment to open flows of both trade and data is a common thread that links Canada and Japan, in addition to numerous other partners in the G20. Both economies are dependent on achieving a fluid transit of data, while simultaneously managing national security risks from malevolent actors in the cyber domain—principally, but not exclusively, China and Russia. Both countries repeatedly promote and support the rules-based international order and have taken important steps to show their unity on areas in other domains, such as regional security co-operation on the Korean peninsula. Co-operation on data governance should be no different and is a critical area for greater cohesion between like-minded democracies.

Ottawa should endorse Tokyo’s efforts to promote better data governance at the G20. Both sides should point to the important strides made towards a progressive approach in areas such as e-commerce, in landmark trade deals, such as the CPTPP and the Japan-European Union Economic Partnership Agreement (Japan-EU EPA). In the latter deal, Tokyo and Brussels helped manage domestic tendencies to protect data and privacy through adopting a reciprocal data adequacy agreement, which allows a freer flow of information with trusted partners. These steps can form the basis of a new, data-centric, international trade regime that relies on data as the new fuel for the global economy.

Many states, such as Japan and Canada, see the benefit of free and open data, but inaction on global data governance means prolonging the status quo of muddling through with state-centric barriers. This option is unsustainable, both in the short and long term, and will only constrain economic growth while widening the vulnerability gaps exploited by authoritarian regimes.

J. Berkshire Miller is a senior fellow with the Japan Institute of International Affairs and the Asian Forum Japan. Brian Lee Crowley is managing director of the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.