The Trudeau government’s recent foreign and defence policy statements have shown a more muscular approach to international affairs, writes Eric Lerhe. But it also reveals a continuing passivity in the Indo-Pacific, specifically as it relates to China’s rise.

The Trudeau government’s recent foreign and defence policy statements have shown a more muscular approach to international affairs, writes Eric Lerhe. But it also reveals a continuing passivity in the Indo-Pacific, specifically as it relates to China’s rise.

By Eric Lerhe, July 4, 2017

Observers of Canada’s recent foreign policy and defence announcements were impressed by the more “hard hitting” and “muscular” tone taken by the Trudeau government. Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland bluntly criticized Russia’s “illegal seizure of Ukrainian territory,” stating that this was not “something we can accept or ignore.” Action backed this up as she outlined the Canadian Armed Forces will soon depart for Latvia in support of NATO. Moreover, free riding on US military power was rejected as it would “make us a client state.” Separately she declared the policy was “about us standing on our own two feet.”

The government’s Defence Policy Review echoed elements of this more vigorous approach and added a significant, if delayed, defence budget increase. Russia was again critiqued for its “illegal annexation” of the Ukraine with a second entry cautioning all as to the potential for Russian forces to “project force” from its Arctic bases into the North Atlantic sea lanes.

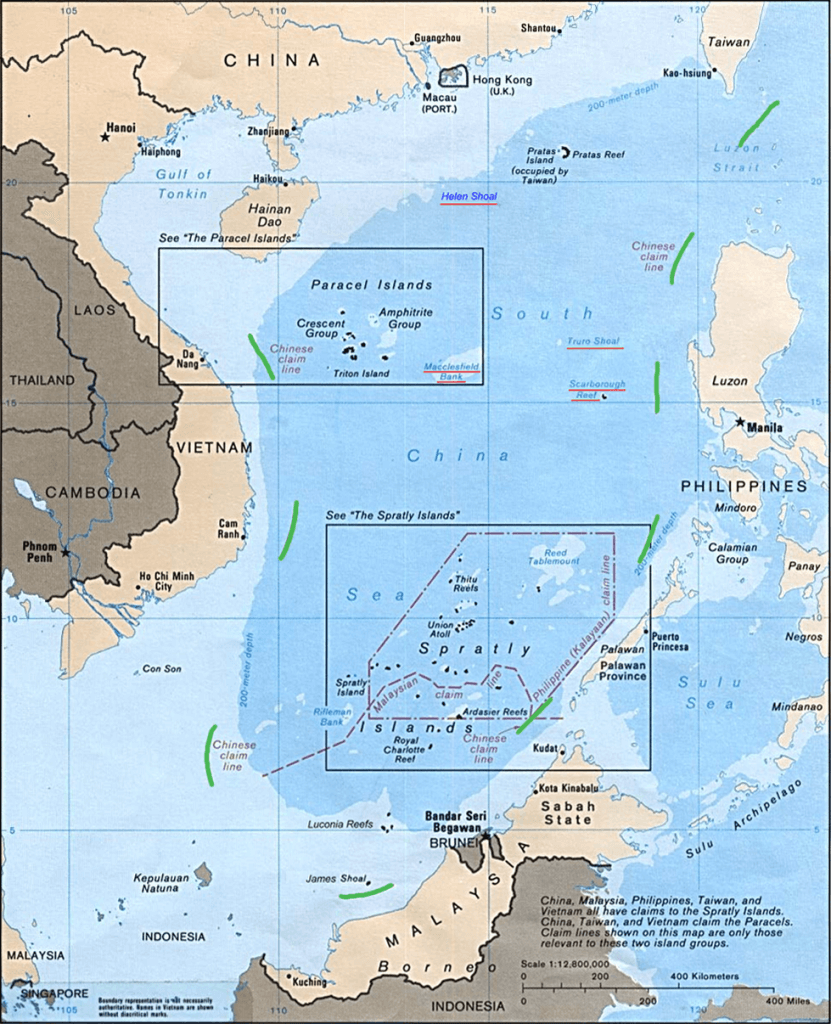

The only disconnect here, and it was quickly seized on, was the failure to discuss China in any detail. Minister Freeland only referred to it as part of an Asia rapidly emerging on the world scene. In the Defence Policy Review statement, China’s island building in the South China Sea only merited an indirect reference that called on “all states in the region” to peacefully manage and resolve disputes. China’s complete rejection of the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague finding against her activities there received no mention. Where 450 Canadian troops are being sent to Latvia, backed up by rotations of our frigates and fighters, on top of 200 Canadian military trainers already in Ukraine, Canada will only dispatch ships and aircraft to exercises and some high-level visits by officials to the Indo-Pacific, according to the new policy.[1]

This passive approach to the Pacific is not new and stretches back at least two decades. However, that passivity regarding China now stands in stark contrast to the vigour of our new foreign and defence policies. Here two points are salient. Foreign Minister Freeland first called for Canada to support a US ally that was showing signs of weariness over its global defence burdens. Then she outlined that the middle powers need to step forward so as not to leave the resolution of all security issues to the great powers. The defence policy specifically mentioned that Canada needs to work with Australia and New Zealand on Indo-Pacific security issues in addition to the US.

This passive approach to the Pacific is not new and stretches back at least two decades.

Yet Canada’s new policies do not seem to offer these nations much support, even in terms of rhetoric, let alone actual assistance. At the June 2017 Shangri-La Dialogue, Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan’s sole comment on China involved reminding all that we had established diplomatic relations with her 1970. The contrast to Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s address could not be starker:

A coercive China would find its neighbours resenting demands they cede their autonomy and strategic space and look to counterweight Beijing’s power by bolstering alliances and partnerships between themselves and especially with the United States.

China’s media heavily critiqued Prime Minister Turnbull’s address while their government protested a combined New Zealand-Japanese statement released in May 2017 that called on states to resolve their disputes in the South China Sea in line with the last year’s 2016 Hague Arbitration Court ruling. Singapore faced similar Chinese critiques for supporting the ruling, perhaps explaining why China snubbed the city-state by not inviting her to its prestigious Belt and Road Forum earlier this year. Yet nowhere in Canada’s new policies is there a similar call for states to respect Permanent Court’s decision.

China’s anger with any state that supports the Court’s decision is likely less due to an offended sense of sovereignty than it is for that decision’s potential to disrupt her long-term strategy in the region. China has used her always dubious Nine-Dashed Line (see the green dashes in the image below) to claim most of the South China Sea, seize key rocks and outcroppings, and then build major military installations on them. Peter Layton, writing for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, argues that these facilities will extend Chinese air power dominance over its neighbors as far south as Borneo.

While Australia and New Zealand have provided diplomatic support, the only direct assistance to the challenged states has come from United States, which must also focus on the danger from North Korea. Despite the occasionally erratic turn provided by President Trump, his administration has unambiguously supported the Permanent Court’s ruling. It has warned China not to build on the Scarborough Shoal, which today is the last unfilled gap in their air and sea control of the South China Sea, and this appears to have briefly restrained her. The United States has also directly challenged China’s now unambiguously illegal claims of territorial seas and economic exclusion zones about those islets with the most complete freedom of navigation exercises to date. Both those actions were significantly more robust than the Obama administration’s confusing and halting efforts.

However the increasing reputation of the Trump administration for a transactional foreign policy has resulted in regional states remaining worried over the potential for the US to place a higher priority on getting China to restrain North Korea than on restraining China in the South China Sea. That presented Canada a perfect opportunity to put into action Foreign Minister Freeland’s vision of Canadian middle power leadership. Indeed, Edward Luttwak, arguably America’s greatest modern strategist, recently argued that Canada, as “the most globally significant of all middle powers,” should do much more to counter China while encouraging her towards a less destabilizing posture.

The United States has also directly challenged China’s now unambiguously illegal claims of territorial seas and economic exclusion zones about those islet.

Defence Minister Sajjan’s Shangri-La Dialogue address in June provided a list of reasons why we should, including the increased role of the Indo-Pacific in providing most of Canada’s recent immigrants, our rising trade with the region, our forty-year membership as an ASEAN dialogue partner, and our long Pacific Coastline. Yet our recent foreign policy and defence announcements all suggest Canada will do very little with regard to reassuring allies in the South China Sea dispute or demonstrating Canadian leadership, noting the Royal Canadian Navy exercise participation in the region has increased significantly this year.

In seeking to explain how Canada can be “muscular” towards Russia, yet passive toward China, recent events are starting to very strongly suggest Canadian caution has everything to do with the Liberal Party’s drive to achieve a free-trade agreement with China, quickly and in Conservative MP Tony Clement’s view, “almost at any cost.” One of the costs appears to be silence on China’s actions in the South China Sea. Earlier, Brock University’s Charles Burton has argued the reason Canada’s did not “openly and firmly” stand up for the Permanent Court’s decision on the South China Sea was connected to Canada’s efforts to join the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. This type of linkage might also explain the bizarre NORSAT sale in the view of many. Here the government allowed the sale of a Canadian company doing extensive defence sales to the US without a formal security review and without being able to back up its claim it consulted with the US.

Canadian caution has everything to do with the Liberal Party’s drive to achieve a free-trade agreement with China, quickly and…“almost at any cost.”

According to the Globe and Mail, Commissioner Michael Wessel of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which reports to Congress, indicated that “Ottawa appears to be willing to sacrifice the national-security interests of its most important ally in exchange for a bilateral free-trade deal with China.” Both Canadian national dailies questioned this sale, with the Globe and Mail declaring “the government appears to have put China’s interests ahead of those of its allies, the U.S. included.” David Mulroney, our former ambassador to China, nicely concluded this episode by referring back to the just-released defence policy and asking “What is the point of elaborating an expensive defence procurement plan if you’re not doing the basics to counter other threats to national security?”

To be clear, there is no rational argument against Canada carefully negotiating a free-trade agreement with China. Australia and New Zealand both have trade agreements with her. What is being questioned in Canada is, in Andrew Coyne’s critique, the “pell-mell rush,” and one-sided readiness to appease China on this topic at the cost of our allies.

At the same time, the government must recognize that the credibility of its well-received defence and foreign policies is at risk for the same reasons. They hold Russia to account while giving China a free pass. More seriously, its claim that Canada is ready to support allies and provide leadership as a middle power is being revealed to only apply under the same lopsided calculus.

Canada can only reverse this by adopting the same semi-permanent stationing of our air and sea forces to the Indo-Pacific as it does in Europe. Similarly, the call to cooperate with Australia and New Zealand in security building efforts in the region must be expanded to include most importantly Japan, but also with Korea, Singapore and the Philippines. Only by adopting an active, more muscular approach in the Indo-Pacific will Canada finally be treated seriously as a security partner in the region.

Dr. Eric Lerhe served in the Royal Canadian Navy for 36 years with his last post as Commander Canadian Fleet Pacific. In that role he was a Coalition Task Group Commander for the Southern Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz sector during the War on Terror. On retiring he commenced his doctoral studies at Dalhousie. His PhD was awarded in 2012 and he continues his research into security issues as an independent scholar.

[1] For the suggestion to compare the Canadian response to China with its actions towards Russia I owe Danny Lam.