By Alexander Raikin, April 20, 2023

Paramedics rushed “Mr. S” to the Emergency Department of Mount Sinai Hospital. It was an apparent suicide attempt: shortly after receiving a new diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic cancer, he took what his doctors described as “quite a lethal” dose of his prescribed pain medication (hydromorphone). The staff on duty saved his life – and then started assessing his capacity for medical assistance in dying (MAiD).

Mr. S never applied for MAiD. He never made any official requests for MAiD. But while Mr. S was recovering in the ER, two other physicians not connected with his primary care approached him to talk about MAiD. “That’s where we met him. That’s where we also learned that he had inquired about making a request for MAiD with his family doctor two weeks prior,” although “nothing had sort of been initiated.”

Instead, the physicians deemed that “this was sort of him taking matters in his own hands.” What started as a suicide attempt turned into “query suicidality” – a medical term for an uncertain diagnosis in clinical reports. “When we met with him that day in the emergency, I think we both felt that he was making a capable request for MAiD.”

We know about Mr. S because his case was described as part of the University of Toronto’s Joint Centre for Bioethics seminar series on March 24, 2021, a public seminar frequently attended by clinicians. Some of the attendees were uncomfortable. “Why would you assess capacity for MAID when a patient had untreated physical distress?” a participant asked on Zoom. “We would not accept a request until that was explored….”

John Maher, a psychiatrist specializing in treatment-resistant mental illnesses and the editor-in-chief of the Journal of Ethics in Mental Health, is more critical. After reviewing a copy of the seminar, Maher described it in an email as “bizarre.” “To offer MAiD in those circumstances, to say there is no psychiatric component (adjustment disorder? depression?) to be sorted out, and to discuss MAiD while no attempt has been made to address physical suffering is shocking to me.”

This isn’t supposed to happen. David Lametti, the Minister of Justice and Attorney General, long promised Canadians that MAiD can’t happen the next day, that there are de facto waiting periods already, and no one in a state of crisis would be given MAiD. “It’s not the case that somebody just walks in off the street and says, I would like to have MAiD,” Lametti said in 2019 in a webinar for Dying with Dignity Canada.

So why are we now hearing about doctors nudging a suicide attempt to turn into an assisted suicide?

Over the last two years, I have been investigating the ways that MAiD safeguards have been circumvented. We knew that mistakes were made when MAiD was first legalized. In 2017, the National Post reported that because of MAiD, according to the Quebec’s College of Physicians, emergency physicians erred by letting suicide victims die, even though their conditions were treatable.

And last year, I received a tip: While Mr. S didn’t go through with MAiD, others in crisis following a suicide attempt have done so, despite denials from MAiD providers that attempting suicide disqualifies an individual for the program. Moreover, the leading organization that trains MAiD providers not only knew about the practice, but privately endorsed it – even though a leading board member warned it would violate the public’s trust and could be in violation of the law.

Suicide and MAiD were meant to be separate. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in Carter that “vulnerable persons” could be protected “from being induced to commit suicide at a time of weakness” through proper safeguards. Justin Trudeau’s government agreed. The most recent expansion of MAiD created two tracks: After being deemed eligible for MAiD, the clinician then decides if their patient’s “natural death has become reasonably foreseeable,” an undefined term. If they do, they qualify for “Track 1”; if they don’t, then “Track 2.”

The most important procedural safeguard is that for Track 2 cases, MAiD cannot be completed until the end of a minimum 90-day assessment period. When people with only mental illnesses qualify for assisted suicide next spring, this 90-day buffer will likely become even more important.

Yet, there are some indications that suicide through MAiD is already happening. David Lametti caused controversy recently when he said that MAiD exists because “suicide generally is available to people” and MAiD provides suicide in “a more humane way” to people “who, for physical reasons and possibly mental reasons, can’t make that choice themselves to do it themselves.” But are suicide attempts now being diverted into MAiD?

I asked the most important MAiD experts. Stefanie Green, a prolific MAiD provider and the president of the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP), told me last June that “suicide and MAiD are completely different” because – borrowing a quote from Tim Quill, a palliative physician supportive of assisted dying – “suicide implies some form of self destruction; assisted dying involves a form of self-preservation.” Much of this distinction is rhetorical. Regardless of what activists and physicians believe, the federal legislation that permits euthanasia and assisted suicide explicitly created “exemptions from the offences of culpable homicide” and “of aiding suicide” for clinicians like Green.

In turn, CAMAP claims to represent the national body of MAiD experts. There is no competition. Its website describes its goal “to establish training resources, to create medical standards, and to encourage the standardization of care across the country.” Last July, Health Canada announced that it will allocate $3.3 million for CAMAP to develop the national training curriculum for MAiD providers and assessors.

This decision wasn’t surprising. In practice, much of the clinician training for MAiD –from gauging whether someone has the capacity to consent to MAiD to the method of inserting the double saline drip to inject someone with the lethal combination – already comes from CAMAP resources. When Lametti said that we need to listen to physicians on who should be eligible for MAiD in practice, effectively he is referring to CAMAP.

Consider some of the documents already in use. Reasonably foreseeable death means, as a CAMAP training document states, that a patient either has a “death expected within x years” or has “a predictable trajectory to death,” the latter which means it is an “open question” if you can create your own predictable trajectory by saying that you will refuse to eat or by attempting to take your own life. What does that mean?

Jocelyn Downie, a law professor who argued successfully for decriminalization of assisted dying to the Supreme Court, presented this document to CAMAP. In April, I asked her about it. She told me that comparing suicide and MAiD is “comparing apples and oranges” – in short, it’s “a logical fallacy.” “The people who would attempt suicide who are then unsuccessful, it’s not as if they would get MAiD, so it’s not as if they would end up dead,” she said.

Downie is adamant. “They won’t get MAiD. They don’t qualify for MAiD. You know, that’s the thing. You’re not showing up in a suicidal state and you get MAiD tomorrow, you know? So the very same person, if you stop them from taking sleeping pills and you said, you have to wait 90 days until you can have it,” she said. “I’ll give you the sleeping pills back after 90 days, they’re not going to complete the suicide after 90 days. But the same thing, they’re not going to have MAiD, because they’re going to rescind the request.”

But privately, in a Word document shared to CAMAP members, MAiD providers were given a different answer. CAMAP coordinates a regular case sharing session between MAiD providers. An authenticated summary of that session was sent to me.

In it, Ellen Wiebe, a director of CAMAP, asked a law professor to answer a question on the case of “a person” who “suffered injuries from a suicide attempt (Drano) that left them with pain and disability that led them to ask for MAiD.” This individual received MAiD under Track 1 – without the legislated 90-day assessment period in Track 2. Now, after the patient already qualified and died through MAiD, there were questions.

“Are we allowed to consider risk of aspiration pneumonia from a suicude [sic] attempt or risk of sepsis from quadriplegia caused by a motor vehicle accident to be natural deaths (even though the coroner calls them not natural)?” the memo asks. The question is stark, even though it was asked post facto: Track 1 of MAiD requires a “natural death that is reasonably foreseeable.” If the death isn’t natural, any clinician involved could face criminal charges.

The memo affirms that the right decision was made. “Patient with risk of aspiration pneumonia from a suicide attempt (and refusal of treatment for pneumonia) and patient with risk of sepsis from quadriplegia caused by a motor vehicle accident (and refusal of treatment for sepsis) to be natural deaths can be found to meet NDRF [ed. natural death is reasonably foreseeable] requirement,” notwithstanding the coroner’s report.

But another participant in the briefing thought this was the wrong decision. Jonathan Reggler, another prolific MAiD provider, the co-chair of the Clinicians Advisory Council for Dying with Dignity Canada, and a board member of CAMAP and Dying with Dignity Canada, in private worried about the risk, albeit not for the patient. Rather, Reggler’s concern is what the public – or “an anti-MAiD prosecutor” – would think if they found out about this conversation.

“The risk is such a case still being seen as suicide completion,” Reggler wrote on June 10 of last year in CAMAP’s general forum, because “removing the requirement for a specified (90 day), not-to-be-shortened assessment period would allow their MAiD to go ahead quickly, once capacity has been established.” The result is “possibly a court case,” and “undoubtedly a prolonged period of stress and emotional discomfort on the part of the Provider” while the prosecutor mulls over the case.

Reggler concluded his note by imploring other CAMAP members. “It would be foolish of us to imagine, as MAiD clinicians and supporters, that the issue of ‘optics’ of such cases are of no relevance on the national stage,” Reggler wrote.

Reggler, CAMAP, and its president, Stefanie Green, did not respond to requests for comment. A spokesperson for the RCMP could “not confirm or deny” if the case discussed internally in CAMAP was or is being investigated.

Downie denies that the comments to CAMAP constituted a “legal interpretation,” only that it “explained the law… in relation to the question as asked.” She states that there is no contradiction between her interview comments and the CAMAP memo. “In the interview, I said that people will not be ‘showing up in an ER, in a suicidal state, and you get MAiD tomorrow,’” Downie wrote in an email. “The person who ‘shows up in an ER, in a suicidal state’ will first have their suicidal state attended to.”

The “optics” on what is a suicide matter, especially as the relationship between MAiD and suicide grows. MAiD was meant to save lives by reducing the number of suicides. The Supreme Court in decriminalizing assisted suicide was swayed by the “harm avoidance” argument that to save the life of a person like Mr. S requires to give him a choice to end his life through a physician; otherwise, he would take his own life before he would have preferred to die. Thus, to save a life requires the ability to end it.

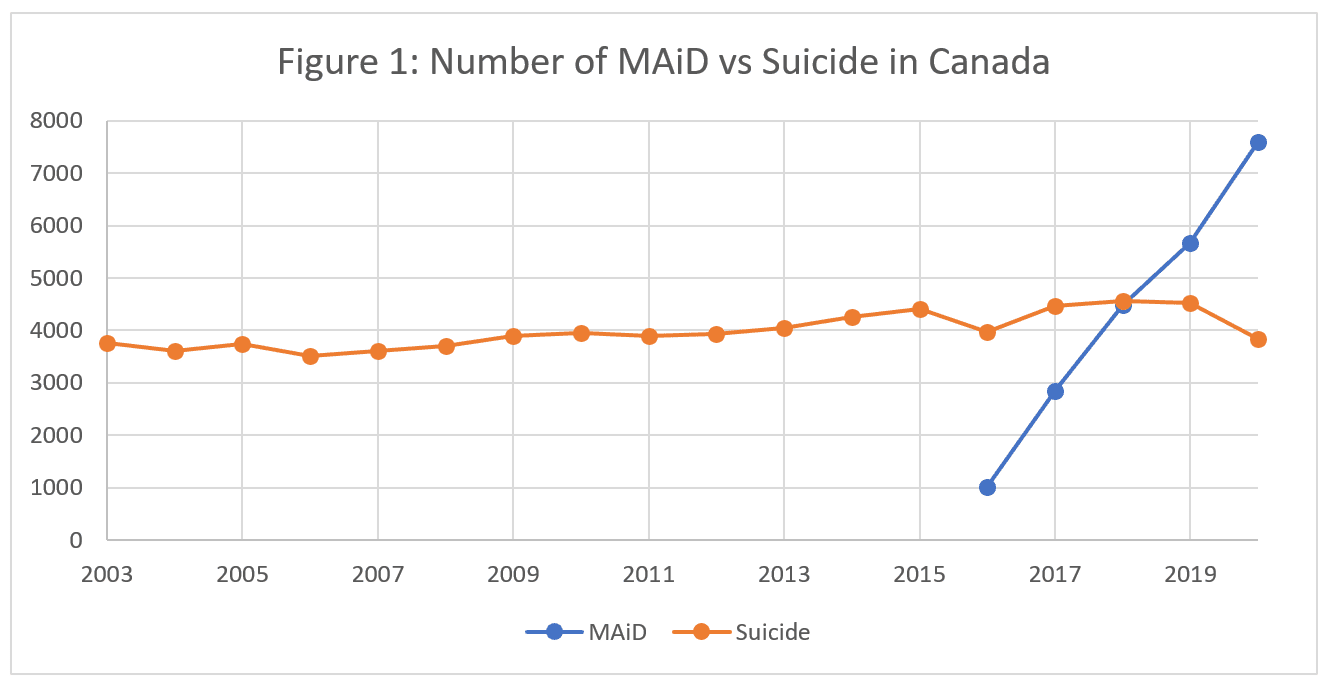

The data tells a different story – a trend well-documented in other countries. Instead, in Canada, the number of MAiD cases increased by seven-fold between 2016 to 2020, the last year we have data on suicides; the number of suicides has remained essentially flat since at least 2003 (Figure 1).[1] Canada’s suicide rate used to be below the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average, in 2020 around 11.3 per 100,000 population. But if you include assisted and unassisted suicides in Canada, Canada now has among the highest suicide rates in the OECD at 30.1 suicides per capita – handily beating even South Korea (24.1), the previous leader.

I showed this data to Trudo Lemmens, a law professor at the University of Toronto. (For a more sympathetic view of the relationship between MAiD and suicides, I reached out to Tyler Black, a suicidologist in support of MAiD, but Black did not respond to multiple email requests for an interview.) “I always thought this is interesting,” Lemmens said. “We insist on evidence, but the Supreme Court made this statement based on no evidence for that. You can intuitively think that [the claim that legalizing MAiD will reduce suicide] is an appealing idea, but the reality is it doesn’t show it.”

In a year, people with only mental health illnesses – at least a third of Canadians – could qualify for MAiD. The Expert Panel on MAiD and Mental Illness, chaired by Mona Gupta, a psychiatrist, recommended to Parliament that no additional legal safeguards are warranted. She previously said in 2021 that these cases would have “been under psychiatric care for years if not decades” before being eligible for MAiD. “Patients who have problems accessing care are not candidates for accessing MAiD.”

Last June, I asked Gupta about the recent cases of suicide attempts turning into MAiD. “The larger question of whether somebody who has made a suicide attempt should at some point be allowed to be eligible for MAiD and how far into the future that should have to be [is] a clinical judgment issue,” Gupta said. “It is also the case that there are people who make suicide attempts, who don’t die, who are quite physically compromised and who then in short order refuse treatment, and then die because of that.”

“We are already allowing it,” Gupta said. “We might not want to allow that.”

Alexander Raikin is a Canadian writer in Washington, DC.

[1] Suicide statistics are delayed by two years. Statistics Canada has not posted an estimate for the number of suicides for 2021. The number of suicides for 2020 is an estimate, likely undercounting the true number. See https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310080101