By Philip Cross

October 27, 2022

Overview

Lower gasoline and house prices helped to slow headline inflation, but core inflation continues to accelerate. Persistently high price increases risk a wage-price spiral that would mean interest rates would rise further and for longer even as the economy slows. Wage increases will be hard for employers to resist after the pandemic and government transfers to households led to structural changes in the labour market, especially high job vacancies, that facilitate higher wage demands.

Headline inflation is receding slowly

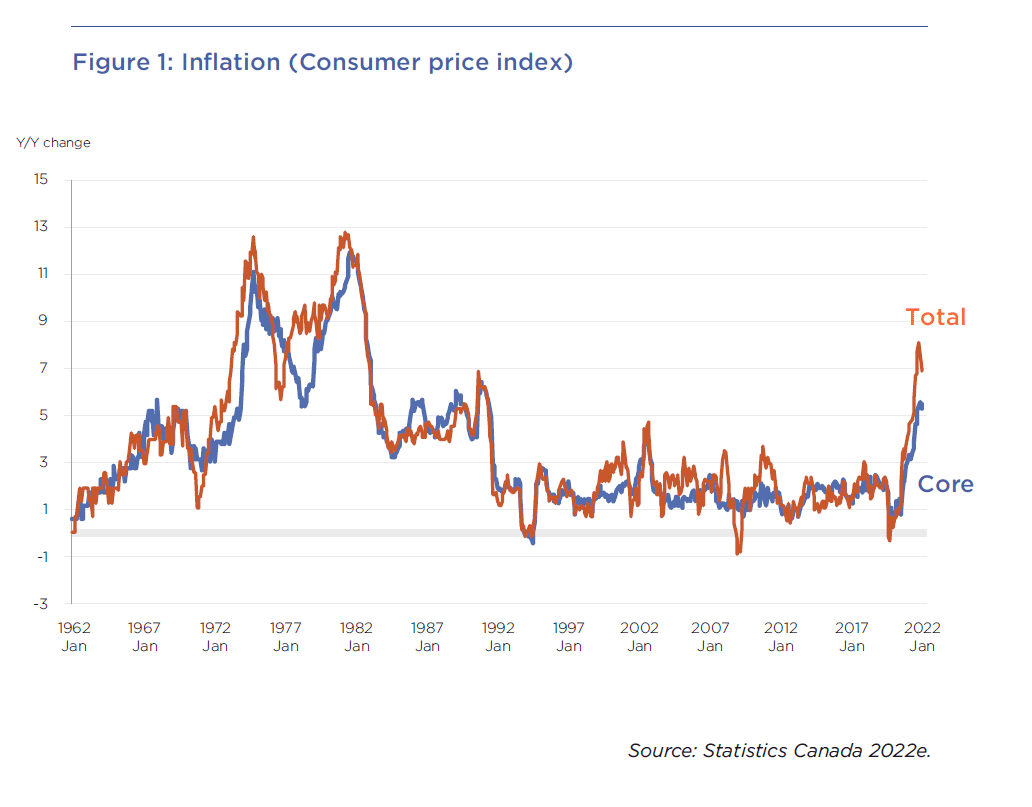

Headline inflation in Canada and the US subsided slightly from its recent highs, dampened by gasoline prices retreating from record highs. The total consumer price index (CPI) in Canada rose 6.9 percent year-over-year in September, down slightly from 7.0 percent in August. However, core inflation in Canada (which excludes food and energy prices) continues to accelerate, to 5.4 percent in September. (Figure 1). In the US, headline inflation of 8.2 percent was accompanied by a 6.6 percent increase in core inflation, the most in 40 years. The persistence of high inflation in North America triggered another drop in financial markets as central banks reaffirmed their commitment to tighten monetary policy. In the past year, households in Canada saw their wealth shrink by 6.1 percent, exceeding their loss during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis.

While some decry the tightening of monetary policy as futile, it already has dampened headline inflation in Canada and the US. The prospect of a slowdown in the global economy was a major factor in crude oil prices falling from their peak earlier this year, lowering prices at the pump. In Canada, house prices also retreated from record highs as demand plunged over one-third in response to higher mortgage rates. While homeowners were initially reluctant to lower prices, the reality of a rapidly slowing housing market inevitably resulted in lower prices. Headline inflation will subside further as food prices moderate from their recent double-digit increases after a bumper crop in North America is harvested.

Core inflation accelerates

Lower prices for high-profile items such as gasoline, food, and housing have not cooled inflation in other areas. This reflects the persistent upward pressure on wages from a tight labour market as well as a lower Canadian dollar. Policy-makers severely underestimated the turmoil in labour markets from the pandemic, as demand recovered faster than expected while supply was transformed by people leaving their former jobs and sometimes quitting the labour force altogether.

Core inflation may remain stubbornly high in Canada where inflation is the most entrenched among the 10 economies studied by The Economist. Indeed, Canada is just ahead of the US. This ranking is based on five indicators — namely, “core” inflation excluding food and energy prices; the dispersion of inflation among the sub-components of the CPI; labour costs; inflation expectations; and Google searches for inflation (The Economist 2022a). By comparison, inflation was less entrenched in Europe outside of Britain, and almost not at all in Japan. Canada’s high ranking for entrenched inflation shows its inflation cannot be attributed only to international factors.

Stubbornly high inflation underscores how central banks incorrectly diagnosed the source of supply disruptions because of the pandemic. Much of the focus during the initial upturn of inflation in 2021 was on the supply of imports, especially from Asia. However, new work from the IMF (Malacrino, Mohommad, and Presbitero 2022) found that supply chains held up better than is often assumed. As a result, the volume of global imports has recovered to its pre-pandemic level faster than the recoveries starting in 1982 and 2009. Instead, it was the disruption to labour markets in Canada and the US and to energy in Europe that has proved the most long-lasting and damaging.

The persistence of core inflation also reflects the limited understanding economists have of inflation dynamics. This was acknowledged by Fed Chair Jerome Powell, who admitted “We now understand better how little we understand about inflation” (quoted in Greenwood and Hanke 2022). Most economists apparently share this lack of understanding about inflation; by the end of 2021, inflation was more than double the median forecast of economists made only eight months earlier (Ip 2022a).

Clearly the Fed did not understand the role of the money supply in fuelling inflation. In a 2021 congressional hearing, Powell said, money supply “doesn’t really have important implications. It is something we have to unlearn, I guess” (Greenwood and Hanke 2022). As Greenwood and Hanke (2022) wryly observed, one of things Powell and “other central bankers must ‘unlearn’ [is] their disdain for monetary analysis.” Frustrated by repeated Fed errors, Allianz chief economic advisor Mohammed El-Erian (2022) tweeted that central bank independence is becoming hard to justify “when four big operational errors (of analysis, forecasts, actions and communication) are accompanied by a lack of accountability.”

It is true that simple-minded monetarism has not proved adept at managing the economy. This is because the money supply is hard to define, especially in periods of financial innovation and regulatory change. The relationship of the money supply to the economy is variable enough to invalidate Milton Friedman’s recommendation of replacing the central bank with a computer that steadily increases the money supply. Friedman himself admitted in 2003 that “The use of quantity of money has not been a success … I’m not sure I would as of today push it as hard as I once did” (quoted in Ip 2022b).

Nevertheless, the money supply conveys valuable information about the economy; economists who incorporated the rapid expansion of the money supply in 2020 into their inflation forecasts were markedly more accurate than central bankers, who based their forecasts on the amount of slack in the economy and expectations about inflation. For example, Larry Summers, Olivier Blanchard, and Jason Furman all voiced concerns in 2020 that the combination of powerful fiscal stimulus, high household savings, and easy monetary policy would overheat the economy (Bernanke 2022, 275) Their analysis emphasized the growth of nominal demand in creating inflation rather than the focus of central banks on the unemployment rate.

While economists have a poor understanding of inflation dynamics, it is clear that monetary policy is one proven tool to fight inflation. As former Fed Chair Paul Volcker concluded, the central bank is “the only game in town” when it came to inflation (quoted in Bernanke 2022, 43). It is important to adopt the best policies to quickly lower inflation. The longer inflation persists, the more embedded it becomes in inflation expectations and the greater delay in the return of lower interest rates. For example, while Paul Volcker is widely credited with breaking the back of inflation during the severe recession in 1981-1982, it is notable that bond rates remained above 10 percent until 1985 (Meltzer 2012, 130). Volcker also advocated the need for large moves in interest rates, such as seen in North America this year, because small, steady hikes to short-term rates “tended to be too little, too late to influence expectations” (quoted in Timiraos 2022, 39)

Curbing inflation without relying on monetary policy has proved ineffective in the past. In theory, withdrawing fiscal stimulus also could close the gap between demand and supply, but the reality is that austerity is only adopted during a fiscal crisis when governments are forced by debt markets to curb their borrowing. Wage and price controls failed abysmally in the 1970s, partly because they distort the supply response to higher prices. Public appeals to households and firms to voluntarily limit price increases, such as former President Gerald Ford’s WIN (Whip Inflation Now) campaign in 1975, proved no more effective than US Army sound trucks playing Strauss waltzes “to encourage nostalgia in enemy ranks while broadcasting surrender appeals” during the Second World War (Atkinson 2013, 218)

“Greenflation” versus “greedflation”

So-called “green” policies encouraging a shift from low-cost fossil fuels to higher-cost renewable energy sources have aggravated the upward pressure on energy prices, a process analysts have labelled “greenflation.” Economists have observed that jurisdictions that have moved the most towards renewable energy, mostly solar and wind, have experienced the highest energy prices. Examples include Ontario, after its adoption of a green energy plan in 2009, California, and Germany (Epstein 2022, 211) As well, much fiscal stimulus is justified in the name of expanding green energy infrastructure, notably the misleadingly-labelled Inflation Reduction Act in the US.

The attempt to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels has aggravated the recent run-up in energy costs. In Canada, the increase in the carbon tax early in 2022 added 5 cents a litre to the cost of gasoline at the pump at precisely the moment prices were skyrocketing. Most governments levy sales and fuel taxes as a percent of nominal sales, reinforcing the upward pressure on prices (government sales tax revenue rose 12.2 percent in the past four quarters). Meanwhile, even as gasoline prices subsided over the summer, energy prices were rising for rapidly for natural gas (37.0 percent in Canada and 33.1 percent in the US). The price of natural gas in North America soared as supply was diverted to Europe to replace imports from Russia. The increase in demand was especially pronounced in Germany, where years of encouraging renewable energy while remaining dependent on Russia for natural gas has created a shortfall that the EU Commission estimates will require a 15 percent drop of consumption this winter.

Such a reduction of natural gas consumption inevitably means pronounced hardship for households and forced closures and layoffs for firms. As Germany’s economy minister Robert Habeck admitted, “Gas is from now in short supply in Germany. Even if you don’t feel it yet, we are in a gas crisis” (Reguly 2022). The price of diesel also has risen even as gasoline prices moderated, reflecting a shortage of refining capacity in North America as diesel (which is also used for home heating) is exported to Europe and as US refiners closed 2 million barrels a day of capacity, partly because governments such as the Biden administration sent the message to refiners that “We don’t want these products” (Crowley and Dlouhy 2022)

People who deny that inflation originates in poor monetary and fiscal policies like to point the finger at higher profits, calling this “greedflation.”[1] This ignores that retail profits in Canada have risen only 2.1 percent in the year ending in the second quarter (and profits in the food and beverage industry rose 5.1 percent, less than half the rate of food price increases in the CPI) (Statistics Canada 2022). Inflation is pushing up costs for firms, which often cannot raise prices enough to offset higher costs. In the US, profit margins for non-energy firms fell in the third quarter as softening demand prevented firms from passing on the cost of higher inputs, including wages (Francis 2022). The weaker outlook for corporate profits is why the stock market is reeling in 2022. Most dramatically, Ford Motor Co saw its stock tumble after announcing inflation is raising supplier costs by $1 billion and lowered its projected earnings by even more.

This is not the first time firms were blamed for price increases. President Carter’s attempt to get firms to voluntarily impose wage and price controls in 1979 was rejected, as firms maintained “it meant continuing to blame business for the problem of inflation—a problem that was the fault not of the corporate world but of government regulations and spending” (Phillips-Fein 2009, 241).

In the longer-run, higher profit margins cannot be a source of inflation in a market-based economy. As Coyne noted:

The lesson of past investment booms is that unusually high profits, which might justify valuations higher than previously experienced, almost always get competed away. The great beauty of competitive markets is that consumers are the ultimate beneficiaries of innovation and growth. The share of national output going to profits, and hence company shareholders, has been relatively stable over long periods. (Coyne 2001, xv)

Most industries[2] that sustain high profits over long periods are sheltered from competition via government regulations (such as in Canada’s banking or telecommunications industries) or tariffs on foreign competition. Even for crude oil, it is worth recalling that the majority of global production is controlled by state-run oil producers and not major multinationals (The Economist 2022b)

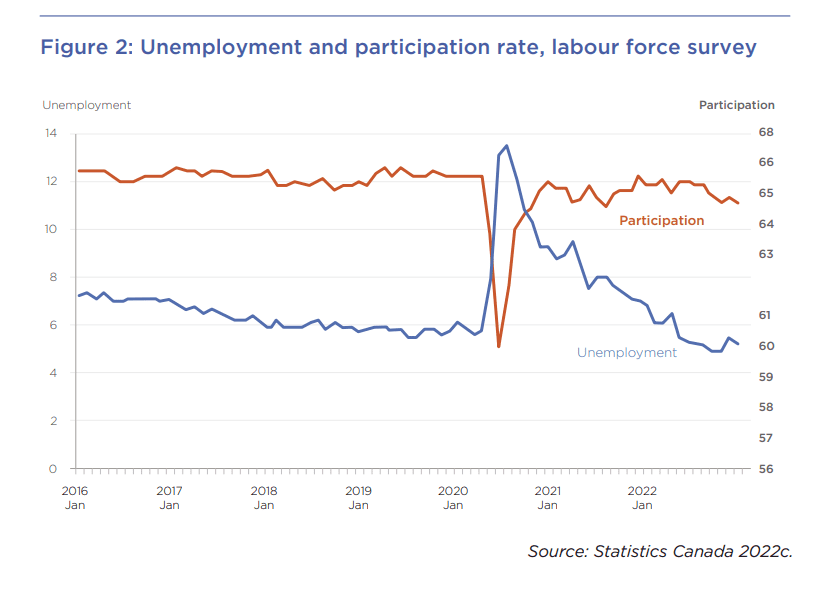

Supply disruptions played a role in higher inflation. However, the disruption of supply extended beyond a shortage of semiconductor chips or delayed shipments from China. Alan Detmeister, an economist at UBS who formerly worked at the Fed, found that “worker quits and job vacancies and supplies delivery times” explained about half the rise in inflation (Ip 2022a). The labour market in both Canada and the US was much more distorted than in European countries, reflecting both a much higher level of government transfer payments and their direct payment to households that severed the connection between employers and employees. Extensive shortages and higher wages have not led to the recovery of labour supply that would have been expected. Instead, the participation rate has fallen to 64.7 percent from 65.6 percent early in 2020 (Figure 2).

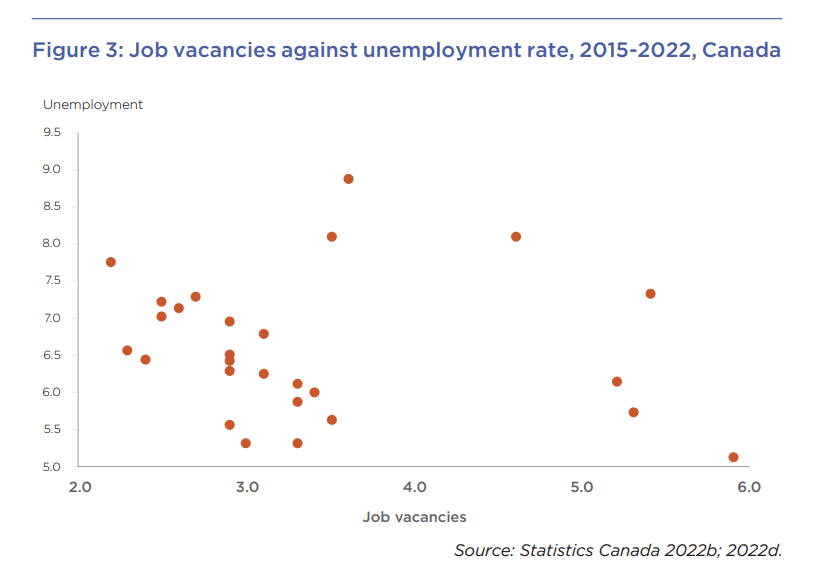

Another measure of labour market distortions from government actions during the pandemic is the pronounced outward shift in the Beveridge Curve. This curve shows the relationship between unemployment and job vacancies. For years, there was a relatively stable relationship where a rising number of vacant jobs in Canada’s labour market accompanied a lower unemployment rate (see the lower left-hand quadrant of Figure 3).

During the pandemic, however, both vacancies and unemployment shifted together to the upper right quadrant (Figure 3). This reflected how Canadians left their former jobs (especially in services industries that require face-to-face interaction such as accommodation and food) to move to a different job or leave the labour force altogether. The direct provision of government income support to workers rather than through their employer (as most European countries did) helped break the link between employers and their employees (Cross 2022a, 5). So far, many former employees have not returned to their jobs and nearly 1 million jobs remain vacant.

Avoiding a wage-price spiral

The concern about inflation becoming entrenched is because it leads to a wage-price spiral and keeps interest rates elevated. A wage-price spiral occurs when the initial burst of inflation leads workers to demand higher wages to compensate for their lost purchasing power. Wage increases that exceed productivity gains boost unit labour costs, which pressures firms to raise prices further.

So far wage data are mixed about whether such a spiral has already begun. Average hourly earnings have accelerated to a 5 percent rate of increase. There have been some high-profile wage settlements, including increases of nearly 14 percent over three years for the 30,000 members of BC’s largest public sector union. However, negotiated wage settlements overall show few signs of accelerating, although these negotiations are concentrated in the public sector where two-thirds of unionized people in Canada work. Governments outside of BC so far have held the line on wages; for example, Bill 124 in Ontario limits public sector wage increases to 1 percent. The moderation of headline inflation in the CPI will encourage workers to keep wage demands moderate.

Capping wages means reversing income gains made during the pandemic

The inability of wages to match price inflation is a two-edged sword. It means there remains a chance of avoiding a wage-price spiral, allowing the Bank of Canada to stop raising rates. However, this would also entail a significant reduction of household purchasing power in 2022, weakening consumer spending and overall economic growth.

Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem recently cautioned business leaders to resist giving in to higher wage demands from workers trying to keep up with rising prices. Regarding higher prices, he told the Canadian Federation of Independent Business: “Don’t build that into longer term contracts. Don’t build that into wage contracts. It is going to take some time, but you can be confident that inflation will come down” (Cross 2022b). Implicitly, Macklem said real wages will fall substantially in 2022 as prices soar, hardly a popular idea but necessary to avoid a wage-price spiral.

The erosion of real incomes due to inflation in 2022 reverses the large gains during the pandemic that far exceeded what could be justified by productivity. Between the onset of the pandemic and the second quarter of 2021 when stimulus peaked, real household disposable income rose 3.0 percent even as GDP shrank 2.8 percent and labour productivity stagnated. Wage hikes in excess of productivity inevitably result in higher unit labour costs, which aggravate the upward pressure on inflation. Since then, real GDP has risen by 4.6 percent while household incomes have shrunk by 1.3 percent, essentially re-aligning their growth since the onset of the pandemic. The one constant throughout was lagging productivity in Canada, which declined 1.3 percent.

Instead of telling Canadians that surging real incomes during the pandemic would soon be reversed by either higher taxes or higher inflation, governments have responded to falling household incomes by pretending to maintain fiscal stimulus even as higher interest rates increase the burden of their debt.

The reality is that falling government transfers to households and rising income taxes have combined to slice 7.0 percent from disposable incomes in the past year. Governments are taking back much if not all the boost they lent to household incomes during the pandemic. The withdrawal of stimulus is overdue, as economists know that once full employment has been reached, stimulus only fuels the excess of demand over supply that sustains higher prices.

Canadians were blind-sided by their loss of purchasing power in 2022 because no one in the federal government or the Bank of Canada warned them their income gains during the pandemic were ephemeral and unsustainable. Government leaders could have explained that if real incomes could be boosted by simply granting wage hikes exceeding productivity gains or sending government checks to people, there would be no poverty in Canada or elsewhere in the world.

The federal government trumpeted a $4.6 billion package to help households, but this includes previously announced measures and represents only 0.3 percent of disposable income. Overall, the federal deficit has fallen from $172.1 billion in the second quarter of 2021 to $15.5 billion in the second quarter of 2022. Provincial governments are transferring more money to households. For example, Ontario sent $500 rebates to drivers just before its re-election in the spring, but soaring revenues (up 20 percent) from inflation swung its budget balance from a $33 billion projected deficit to a $2.1 billion surplus. Rapidly improving government revenues reflect why Milton Friedman famously wrote “inflation has been irresistibly attractive to sovereigns because it is a hidden tax that at first appears painless or even pleasant, and, above all, because it is a tax that can be imposed without specific legislation. It is truly taxation without representation” (Friedman 1991, 25).[3]

The ability of fiscal and monetary stimulus to not just cushion but to raise household incomes during the pandemic in 2020 seemed to be a triumph of stabilization policy. However, those gains have quickly proved to be ephemeral as inflation and interest rates increase, even before the possible long-term damage to housing and financial markets becomes fully evident. Instead of being a transformative event leading to a New Economy based on fashionable ideas like green energy and the “caring” economy, the policy response to the pandemic ultimately is reaffirming old truths about money, deficits, and inflation and the importance of incentives and investment for sustained long-term growth.

About the author

Philip Cross is a Munk Senior Fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. Prior to joining MLI, Mr. Cross spent 36 years at Statistics Canada specializing in macroeconomics. He was appointed Chief Economic Analyst in 2008 and was responsible for ensuring quality and coherency of all major economic statistics. During his career, he also wrote the “Current Economic Conditions” section of the Canadian Economic Observer, which provides Statistics Canada’s view of the economy. He is a frequent commentator on the economy and interpreter of Statistics Canada reports for the media and general public. He is also a member of the CD Howe Business Cycle Dating Committee.

References

Atkinson, Rick. 2013. The Guns at Last Light. Henry Holt & Co.

Bernanke, Ben. 2022. 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19. W.W. Norton & Co.

Coyne, Diane. 2001. Paradoxes of Prosperity: Why the New Capitalism Benefits All. Texere.

Cross, Philip. 2022a. Persistent inflation forces central banks to tighten monetary policy. Macdonald-Laurier Institute Commentary, May. Available at https://macdonaldlaurier.ca/persistent-inflation-forces-central-banks-to-tighten-monetary-policy/.

Cross, Philip. 2022b. “Stimulus-driven income gains couldn’t last.” Financial Post (September 2).

Crowley, Kevin and Jennifer A. Dlouhy. 2022. “Refineries Are the Real Problem.” Business Week (July 18).

The Economist. 2022. “Public enemy.” The Economist (May 14).

The Economist. 2022b. “Nationally determined contributors.” The Economist (July 30).

El-Erian, Mohamed A. (@elerianm). 2022. Twitter post, October 17. 3:42 pm. Available at https://twitter.com/elerianm/status/1582094699484966912?s=20&t=xsYYK3U7yKxMecATAyTdCQ.

Epstein, Alex. 2022. Fossil Future : Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas—Not Less. Portfolio/Penguin.

Francis, Theo. 2022. “Costs Rise Faster Than Prices At Many Big U.S. Businesses.” Wall Street Journal (October 11).

Friedman, Milton. 1991. Monetarist Economics. Basil Blackwell.

Greenwood, John and Steven H Hanke. 2022. “The Fed Ignored the Money Supply, and a Recession Is Coming.” Wall Street Journal (July 7). Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/federal-reserve-ignored-the-money-supply-and-inflation-recession-coming-11657210800.

Ip, Greg. 2022a. “On Inflation, Economics Has Some Explaining to Do.” Wall Street Journal (June 15). Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/on-inflation-economics-has-some-explaining-to-do-11655294432.

Ip, Greg. 2022b. “Inflation Surge Earns Monetarism Another Look.” Wall Street Journal (June 22). Available at https://www.wsj.com/articles/inflation-surge-earns-monetarism-another-look-11655906400.

Lawson, Robert A. 2008. “Economic Freedom and Property Rights: The Institutional Environment of Productive Entrepreneurship.” In Benjamin Powell, ed., Making Poor Nations Rich: Entrepreneurship and the Process of Economic Development. Stanford University Press.

Malacrino, Davide, Adil Mohommad, and Andrea Presbitero. 2022. “Global Trade Needs More Supply Diversity, Not Less.” IMF Blog (April 12). Available at https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/04/12/blog041222-sm2022-weo-ch4.

Meltzer, Allan H. 2012. Why Capitalism? Oxford University Press.

Phillips-Fein, Kim. 2009. Invisible Hands: The Businessmen’s Crusade Against the New Deal. W.W. Norton & Co.

Reguly, Eric. 2022. “Why a lack of courage is setting up Germany for a long, cold winter.” Globe and Mail (June 25).

Statistics Canada. 2022a. “Quarterly balance sheet and income statement, by industry, seasonally adjusted (x 1,000,000).” Statistics Canada, Table 33-10-0226-01, August 24. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3310022601/.

Statistics Canada. 2022b. “Job vacancies, payroll employees, job vacancy rate, and average offered hourly wage by provinces and territories, quarterly, unadjusted for seasonality.” Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0325-01, September 20. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410032501.

Statistics Canada. 2022c. “Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted and trend-cycle, last 5 months.” Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01, October 7. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410028701.

Statistics Canada. 2022d. “Labour force characteristics by sex and detailed age group, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality (x 1,000).” Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0017-01, October 7. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410001701.

Statistics Canada. 2022e. “Consumer Price Index, monthly, not seasonally adjusted.” Statistics Canada, Table 18-10-0004-01, October 19. Available at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000401.

Timiraos, Nick. 2022. Trillion Dollar Triage: How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic and Prevented Economic Disaster. Little, Brown & Co.

Wiseman, Paul. 2022. “Greedflation: Is price gouging behind rising prices?” Globe and Mail (June 27).

[1] For example, see Wiseman (2022).

[2] A few companies with exceptionally strong brand recognition can insulate themselves from competition, such as Apple or Coca-Cola; the difference is that customers voluntarily pay extra to buy these brands, while the unfortunate customers of Canada’s banks or telecommunications companies have no choice but to buy from a very small number of firms. Warren Buffett has based his investment strategy on buying companies that have government-mandated or strong brands to create so-called “moats” around their business model that insulate them from fierce competition and allows them to maintain high profits.

[3] More forcefully, Robert Lawson wrote: “Inflation erodes the value of property held in monetary instruments. When governments use money creation to finance their expenditures, they are, in effect, expropriating the property and violating the economic freedom of their citizens” (Lawson 2008, 116).