By Richard Audas

November 23, 2022

COVID-19, and its growing list of variants and sub-variants, are likely to be with us for a very long time. This reality shifts our thinking about how to assess the impact of COVID on our lives.

Initially, due to fear of the unknown and planning for the worst, governments issued strict measures that impacted all of our daily routines. Normal life ceased in many ways with schools shuttering, businesses closing, public and family gatherings ceasing, and even many medical procedures being placed on hold to preserve hospital capacity. We were quarantined, we had to wear masks and social distance and we had to get tested. Travel within national boundaries was restricted and international travel almost entirely eliminated. Eventually effective vaccines were developed, which became the passport for a return to normal.

This period of the pandemic – from its early days to the rollout of vaccines – was analysed by the Macdonald-Laurier Institute’s COVID Misery Index (CMI) and Provincial COVID Misery Index (PCMI). Both tools were designed to compare jurisdictions (national and provincial) across a variety of measures to better understand how governments performed in protecting human well-being. While much attention was paid to indicators such as cases and deaths, we argued there was much more at play, including economic considerations, impacts on education, excess deaths, long COVID and the elements of human well-being affected by long-term lockdowns.

The CMI project represents a useful tool for understanding what kinds of policies were successful, what trade-offs were imposed by other policies, and what approaches failed entirely. But it was always intended to be temporary and limited in its analysis, focusing on certain peer countries over the period of the pandemic when policies could be actively differentiated throughout the world.

Today, most restrictions have been lifted internationally, particularly for vaccinated individuals, though with the next wave always just over the horizon, some are calling for a reinstating of mask mandates and other possible measures.

So as time has gone on and COVID has become more routine, the statistics we originally used to capture misery have become less reliable and, as such, we feel it’s time to wrap up this project and share the lessons we have learned. What follows is an examination of the key findings that can be derived from the CMI.

Convergence

Developed countries around the world showed important differences in how they approached dealing with COVID. Some of the earliest hit countries – especially those in Europe – had little time to prepare and, to some degree, their responses may have been too late. Once COVID gets in, it’s very hard to get out.

Some countries, most notably Sweden, opted initially to invoke few mandates and relied more on providing the public with good information about the disease. Sweden preferred to ask individuals to make their own choices rather than imposing those choices. Other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, locked down borders and put strict public health restrictions in place.

The “short sharp” lockdown was initially successful, as the levels of COVID remained low (or zero) in these countries for quite a long time. The proactive measures employed by countries like New Zealand and Australia succeeded in the initial phase of the pandemic and, as a result, their overall misery scores derived from factors like deaths and infections were among the lowest measured in the CMI.

Additionally, both countries scored well in response misery indicators, suggesting better performance overall in efficiently managing the pandemic. New Zealand, in particular, enjoyed impressive testing and stringency scores; despite having strong lockdowns, the “short and sharp” strategy meant that, through much of the worst period of the pandemic, Kiwis were able to enjoy far more normal lives than many in the West. This is less true for Australia, which did resort to both strict and long-lasting lockdowns as its strategy faltered.

However, as more transmissible variants emerged and isolation became untenable, these countries have had higher rates of infection for a sustained period of time. The one upside is that these countries have avoided the worst effects of COVID by having their worst outbreaks occur after significant proportions of their populations received vaccinations, reducing the rates of hospitalization and death. This suggests that while this approach can be effective for a time, the only real way toward normalcy runs through access to and uptake of effective vaccines and accumulated immunity through exposure.

With such clear differences in approach, one might expect vastly different outcomes. Yet what is interesting is that Australia, New Zealand, and Sweden all performed similarly well in the CMI’s overall scores.

Though much-maligned, Sweden had slightly above average performance on disease-related misery. Cases and transmission were significantly above average, deaths were somewhat above average, but ICU admittance, hospitalization, and excess deaths all were average. Importantly, Sweden avoided the worst-case outcomes that many critics had warned of.

At the same time, Sweden’s economic performance was among the best of the countries measured. In particular, Sweden’s economy performed well in 2020 and 2021 and they avoided costly public borrowing binges. Sweden scored above average on response misery indicators overall, largely due to its far less burdensome lockdown measures, though its testing regime was never able to quite keep pace.

These countries pursued very different choices in public policy but arrived in similar places in terms of their overall misery. New Zealand was the best performer of the three on every measure as a result of having less COVID overall, but Australia and Sweden are nearly tied in their overall scores, both slightly better in performance than Canada.

This is not to suggest that there are no differences between very different strategies, but that the strategies pursued led to trade-offs that should be fully understood and appreciated. Many policy-makers in Canada assumed there was only one viable strategy to consider before vaccines were available; the CMI challenges us to think differently about the range of choices available.

COVID misery is multi-dimensional

Most of the focus of public health officials, policy-makers, politicians and the popular media was focused on COVID itself: How many new cases? How many deaths? How many people got tests?

However, beyond the disease itself, there have been profound impacts on our well-being and limits to our normal liberties. The merits of trading liberty for better control of COVID are debatable, but it should not be in dispute that giving up personal freedoms comes at cost. Restricting movement, closing provincial and national borders and limiting social gatherings have borne a heavy toll that can never be truly quantified.

So how can we compare the grief of a person who lost a loved one prematurely to COVID against the misery endured by a family that lost their business and sole source of income? The CMI suggests that we should not contest either source of misery by setting them in conflict with each other. Rather, both should be seen as terrible, and a policy that induces one form of misery to prevent another should be understood in a balanced manner. In the same vein, a policy that induces misery without creating clear benefit must be understood as a failed policy.

We need such a multi-dimensional understanding of the pandemic, which was lacking in Canada and other countries as policy-makers navigated change and difficulty through 2020 and 2021. Canada had similar disease misery scores as countries like Norway, Japan, Australia, and Sweden. Yet we paid a far heavier price than those countries on an economic basis during the same period.

This suggests that policy-makers failed to appreciate the unintended consequences of their decisions, whereas other countries did a better job selecting policies that were less misery-inducing. That Norway had both better disease misery outcomes and far better economic outcomes than Canada means there are lessons to be learned from our peers. It is insufficient for governments to be content for having avoided the worst possible outcome when better outcomes were clearly possible.

To achieve these better outcomes, governments in Canada must rethink their approach to make policy-making more holistic. No policy challenge exists in a vacuum, and so no solutions can be designed without a holistic consideration of their effects.

Governments policy matters

In addition to the range of public health restrictions brought in place to restrict the transmission of COVID, the main policy tool to reduce the impact of COVID has been vaccines. The development of effective vaccines to reduce the incidence and severity of COVID is a stunning achievement. While the belief that vaccines would be an effective tool to end the pandemic was overly optimistic, they have reduced the rate of transmission and made an important contribution in limiting the severity COVID for those vaccinated individuals who contracted the disease.

Another factor to consider is that of innovation. At different periods during the pandemic, countries in the CMI over-and-under performed at different times on the basis of access to vaccines. While access has stabilized and this is no longer a major discrepancy, it is important to remember that early access to vaccines not only saved lives but also led to more options for policy-makers to return things to some semblance of normal.

The CMI’s updates tracked how countries who had better environments for research and development secured vaccine access much more rapidly. This is particularly true for the United States and the United Kingdom, whose pharmaceutical sectors not only provided their respective countries with a path out of the pandemic but were able to provide that solution to other countries as well. That being said, early access alone was fleeting in its benefit. As production continued and uptake increased, as second doses shifted to third and forth doses, the discrepancy between countries based on indicators of innovation reduced.

While the scientific evidence on vaccines is consistent, governments varied in their ability to convince people to become vaccinated. Tools like vaccine passports and vaccine restrictions seem to have some effect on individual decision-making, but as demonstrated by phenomena such as the so-called “Freedom Convoy,” such measures are not without their own consequences.

Looking for patterns in uptake across provinces or nations is challenging, but generally jurisdictions with greater trust in their elected officials tended to have higher vaccination rates with much more enthusiastic uptake.

Beyond vaccines, the CMI suggests that fiscal discipline in “good years” carries clear benefits for “bad years.” This seems like a common-sense idea, but it has been anything but common in the western world generally and Canada specifically. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Norway was able to navigate the pandemic with less than a tenth of the relative debt-to-GDP taken on by Canada in 2020. Despite having a substantial sovereign wealth fund, Norway’s economy has some similarities to Canada that are worth considering when mapping out this discrepancy.

The CMI reveals that this has major consequences. Canada’s debt-financed spending binge has contributed significantly to inflation. Norway’s inflation rate, which peaked at 5.3 percent in September, was far more modest than Canada’s peak 2022 rate of 8.1 percent.

All this is to say that policies made before crises are crucial. Canada’s inability to exercise fiscal discipline and benefit as substantially from our robust economy left us vulnerable to the economic effects of the pandemic. As a result, future generations will be left poorer than they would have been if we had pursued different policies prior to the pandemic.

Lockdowns have a cost

The disruptions to everyday life stemming from lockdowns have taken a heavy toll. They kept families and friends isolated from one another, where loved ones couldn’t visit sick or sometimes dying relatives. Businesses and other ventures were mothballed and many will never restart. Hobbies and pastimes were abandoned. There can be no doubt that the cost of the lockdown is well beyond the productivity lost while having people furloughed. Undoubtedly lockdowns did reduce transmission of COVID, but in the future they should remain a last resort and imposed under the most stringent of criteria.

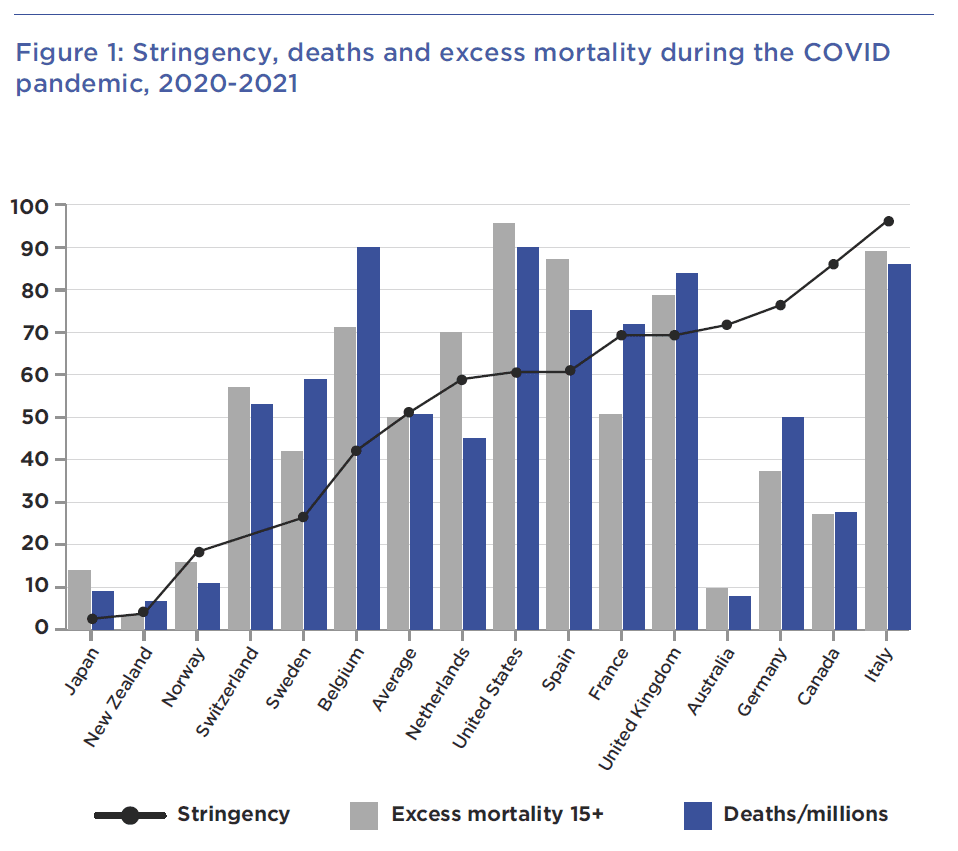

Even so, the benefits of lockdowns as a policy are quite unclear when considering a comparative analysis. In Figure 1, CMI countries are sorted based on the misery score associated with their stringency of lockdown and other restriction measures. The CMI graph shows the deaths associated with COVID and the excess mortality endured during the pandemic.

The graph shows that excess mortality and COVID deaths appear to follow similar trends. This suggests that most excess deaths during the pandemic are generally a result of COVID deaths. But it also suggests that there is, at best, a very unclear relationship between overall lockdown stringency and death prevention – the ostensible goal of lockdowns.

In the first grouping of countries, we see Japan New Zealand, and Norway. These countries have both low overall stringency and low death indicators. Their geographic isolation likely helps to explains this, but these countries also pursued different lockdown strategies. Japan restricted travel for quite some time to foreigners and New Zealand pursued a successful short and sharp strategy, with strict border controls. In any case, these countries’ successes should be examined for future policy development as they were the most successful.

The next group of countries fell somewhere in between. Though stringency varied significantly in this group, it doesn’t appear strongly correlated to COVID deaths or excess mortality. This group is so varied that there are few if any clear insights to garner beyond invalidating the hypothesis that locking down tighter necessarily resulted in fewer overall deaths. It is likely the case that countries with high stringency and high deaths, such as Spain or the UK, implemented reactive rather than proactive lockdowns, which were less effective than the strategies of the previous cohort and more misery-inducing overall.

The next group of countries includes Canada, Germany, and Australia. These countries had relatively low-to-middling results on COVID deaths and excess deaths but endured very strict and/or long-lasting lockdowns. If there were support for the idea that stringency reduces deaths, it would be found with these countries. However, they appear to be outliers against the rest of the data. The most plausible interpretation is that these countries “overpaid” for their success in preventing deaths. That is, they could have achieved similar results with lockdown measures that were more proactive and less long-lasting, such as in New Zealand. Further study is needed to determine precisely why this category of countries is such an outlier against the rest of the data.

The last country is that of Italy. Despite having extremely strict and long-lasting lockdowns, Italy had among the worst outcomes with respect to excess mortality and COVID deaths. This likely has to do with the severity of the wave that struck Italy early in the pandemic. Italy sadly served as a cautionary tale about the worst-case scenario, where late applied lockdowns failed to significantly curb the worst of the pandemic but induced significant misery along the way.

COVID’s long tail

An interesting metric to examine throughout the pandemic was the elevation in all-cause mortality. In the effort to reduce COVID transmission, there was a massive shift of health care resources to limit the spread of the disease and to free up capacity to treat spikes in cases. However, this came at significant cost – with elective procedures postponed or cancelled, and routine screening for treatable cancers neglected. Once screening resumed, cases were found that were beyond the stage where treatment and remission were possible.

Of particular concern is the mental health impact of COVID. Individuals experiencing anxiety and depression, as well as a myriad of other mental health disorders, have seen their situations deteriorate. Social marginalization and mental health conditions often occur simultaneously, and the impact of isolation and lockdowns would have exacerbated many already difficult situations. Families with children on the autism spectrum or with learning disabilities found the disruption of routines and the loss of access to important resources and services difficult.

In a world increasingly moving online and digital, COVID will further change how we interact with one another. While there’s undoubtedly advantages to having online meetings, the longer-term impacts of conducting more of our work, education and socializing online is not well known and will almost certainly be harmful for at least some.

Equally important is the unknown – but likely quite sizeable – portion of the population that will continue to have a variety of COVID symptoms, some of which can be quite debilitating, long after their infection have passed. Long COVID, as the condition has become known, has been getting renewed attention, as infection numbers skyrocketed with the Omicron variant and its sub-lineages while hospitalizations and deaths have fallen. More research needs to be done on long COVID and its causes, as well as the extent of its possible burden on health care system into the future.

The economic cost

One area the CMI had rightly highlighted is the economic cost of COVID and the response to it. For lockdowns and other public health measures to be effective, workers needed to remain at home, businesses had to shut or greatly reduce activity and supply chains were upended. Without government support, the effects on individuals would have been substantial and it is likely that compliance with these restrictions would have significantly suffered.

As such, we observe immediate and sizeable contractions in GDP and employment and massive increases in public spending. In many ways (and not in a good way), Canada was a world leader in increasing public spending. In fact, the level of public debt taken on has not been seen since the Second World War. The accumulated debt will take years, if not decades, to pay off and will likely be inherited by those currently too young to vote or work.

Fearing a global recession during the pandemic, central banks around the world slashed interest rates and implemented other policies to encourage borrowing and lending. Accompanied with government supports for individuals and firms, this led to a rapidly increasing asset bubble with housing and equity markets rising rapidly. While this benefited asset holders, it created a sense of further exclusion for those too young or otherwise lacking resources to get into these markets, which has certainly increased social class and generational conflict.

With increased demand, supply chains struggling to cope, and the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine creating pressures on energy and food prices, the inevitable outcome has been inflation, which is currently at 40-year highs in most affluent countries. The reduction in spending power will impact retirees who will likely experience a permanent reduction in their purchasing power.

Now as housing bubble starts to recede and central banks make borrowing and lending more difficult in order to tame inflation, recessions are looming. More and more homeowners are finding themselves in a position of negative equity (owing more on the mortgage than the home is worth in the current market). The only thing preventing this from causing substantial difficulties in the economy is that labour markets remain tight. However, if the central banks over-reach with their interest rate hikes, the potential for labour market contraction and additional economic misery remain very much a possibility.

Conclusion

COVID has been a global event like no other in most of our lifetimes. The health impact has been substantial and the restrictive public health measures taken have extracted a heavy toll in terms of disruptions to daily life and the channeling of health care resources towards COVID at the cost of virtually every other health condition. We will be counting the health and well-being costs of COVID for a very long time.

Of further and substantial concern is the economic impact of COVID. While new businesses will emerge and many displaced workers will find new opportunities, COVID has been disruptive to the functioning of the economy. What will take much longer to reconcile is the massive debt taken on by many nations and the extent to which this limits governments’ capacity to respond to the next crisis. These observations are clear from the CMI and the recent macro-economic trends across the West.

With policy-makers in Canada once again mulling whether to impose mask mandates or other restrictions, what does the CMI recommend when it comes to protecting human health without harming other aspects of human well-being?

- Stringency, including lockdown strictness, does not have a clear relationship with decreases in deaths. In some cases, it appears that decreased stringency results in decreased deaths. Given what is known about the tremendous costs that lockdowns introduce on society, they should not be considered effective

- Governments should seek to emulate the strategies of the most successful countries. Japan, Norway, and New Zealand all had the best outcomes on health, and did so without imposing as steep costs on their economies and societies in 2020-2021

- Proactive measures are less costly and more effective than reactive measures in managing pandemics. However, once pandemics take hold in a society, the strategies designed to keep them out in the first place no longer become effective

- Preparing for pandemics and managing them effectively also means ensuring that a nation’s public finances are in order. Countries like Canada failed to manage deficits properly before the pandemic, engaged in poorly targeted spending during the pandemic, and now have a heavy economic price to pay in terms of inflation, debt, and economic uncertainty

- Vaccines are the surest path out of pandemics like these; the CMI observed that countries with strong environments for research and development of pharmaceuticals – essentially for the creation of vaccines – were rewarded with earlier access to vaccines.

- However, access is only half the problem; countries that fail to persuade many of their citizens to become and remain vaccinated will pay heavy health prices. The CMI reveals an increasing challenge facing many countries who had early vaccine success, including the United States, who are now less successful at vaccine uptake. The unintended consequences of government action must be better understood and scrutinized; a greater array of policy experts should be available to comment on strategies that have significant bearing on society as a whole.

Quantifying the misery introduced by COVID-19 onto people is a nearly impossible task. The CMI sought to compare, in as comprehensive a manner as possible, the long- and short-term costs being imposed on human well-being. In so doing, the CMI demonstrated that the virus itself has impacts, but so do our interventions.

The countries (and provinces) that performed best were able to employ strategies that protected health, preserved their economies, and only applied strict measures in a short, sharp, and proactive fashion before the widespread uptake of vaccines. They should be the model moving forward; time will tell whether policy-makers can emulate that success.

About the author

Richard Audas, Ph.D. is Professor of Health Statistics and Economics at the Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador. He has contributed expertise related to statistics and economics as well as experience in applying quantitative methodologies to developing report cards related to the educational system in Atlantic Canada, and to municipal report cards for Atlantic Canada and Canada’s major metropolitan centers. Professor Audas’ work has focused on the role of key public institutions and the impact they have on the lives of Canadians. He is the Director of the Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research and the Academic Director of Memorial University’s Statistics Canada Research Data Centre. He holds visiting appointments at The University of Manchester, Bangor University and Otago University.

Professor Audas’ work with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute has included the award-winning Justice Report Card, an examination of opportunities to increase competition in health care and the COVID Misery Index.