This article originally appeared in the Financial Post.

By Heather Exner-Pirot, May 16, 2024

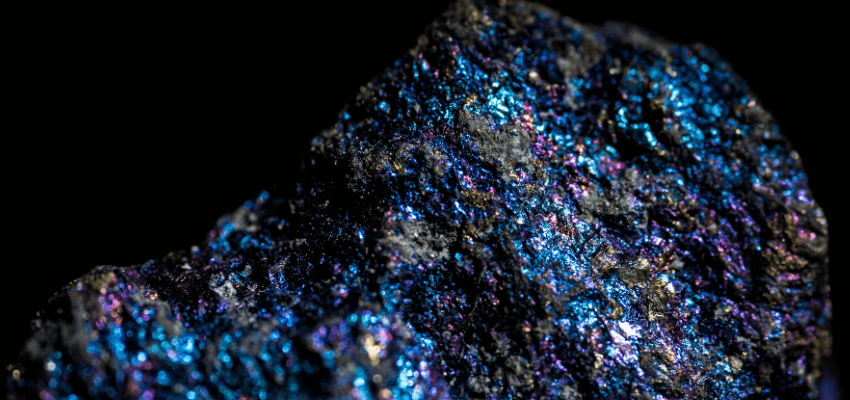

At the time, the opening of a small rare earths mine in the Northwest Territories in 2021 was heralded as an important step in breaking China’s monopoly over this strategic commodity. Rare earths are used in everything from electric vehicles and cell phones to wind turbines and jet engines. China currently extracts more than 60 per cent of rare earth elements and processes as much as 90 per cent of global supply. The case of Vital Metals and the Nechalacho mine show just how far it’s willing to go to maintain a stranglehold on the rare earths market. What was once a hopeful story is now a cautionary tale.

The call to develop friendly supply chains for critical minerals has grown louder in the past few years, with the deterioration in the geopolitical environment, the rising prominence of energy security and continuing urgency about de-carbonizing. Rare earth elements have always been on the geo-political radar, however, both because of China’s control of their mining and processing and its history of weaponizing its dominance through trade restrictions.

Eager to capitalize on the demand for non-Chinese sources of rare earths, Australia’s Vital Metals started extraction at the Nechalacho mine, 110 km southeast of Yellowknife, in 2021. It was touted at the time as a step towards loosening dependence on supplies from China. Vital even announced it was opening a processing facility for bastnaesite rare earth ore in Saskatoon, adjacent to a separate processing facility for monazite rare earth ore being developed by the Saskatchewan Research Council, a crown corporation. Visiting the Vital Metals facility in January 2023, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said we “really need resilience in our supply chains.” Vital received $5 million in federal support for the project.

And then the market fell. Prices for rare earths sank through spring and summer 2023 as demand weakened and China continued supply, displacing new entrants in the market, presumably intentionally. Vital Metals was amongst the casualties. It paused construction of its Saskatoon processing facility in April 2023, and filed for bankruptcy of its subsidiary in September.

Rare earths miner Shenghe Resources of China came to the rescue last October — a wolf in sheep’s clothing if ever there was one — with a 9.99 per cent share buy and an injection of cash. In December Vital agreed to sell the entire stockpile of rare earths mined at Nechalacho to its Chinese shareholder. What was once a symbol of friend-shoring critical minerals became a pawn in China’s plan to preserve its monopoly.

It gets worse. As late as July 31, 2023, Vital announced that the bastnaesite rare earth ore processing facility’s engineering was 80 per cent complete, procurement 85 per cent complete and construction 50 per cent complete, and that despite the pause it was still “investigat[ing] potential pathways for the long-term future and viability” for the project. After China’s investment came through, however, the plant was summarily dismantled and sold in pieces. The brand new equipment went on the auction block last Christmas Eve — a great day for falling under the radar — and was sold to a host of buyers for pennies on the dollar. (The federal government is a creditor and has sought to recoup some of its losses.) All this came just three days after China announced it was banning export of rare-earths processing technology, in which it’s a leader.

The break-up of the Vital facility set the building of Canada’s rare-earth supply chain back years, removing the sole commercial competitor developing capacity for midstream processing in the country. The only other facility in North America is owned by MP Materials and operated in California. Shenghe Resources is the second largest shareholder in that company.

Because China enjoys dominance at every step of the supply chain, rare earths are probably the easiest critical mineral for it to manipulate. But its hands are in other pots, too, including lithium, cobalt and nickel, which are all essential to the electric vehicle and battery industries that both Chinese and western governments are pushing with subsidies and mandates. In total, China is the world’s largest producer of 22 critical metals and seven industrial minerals.

Canada and its allies are still losing ground to China in critical minerals. In many ways we are playing right into their hands, pushing policies that double-down on energy and industrial systems that depend on Chinese products and processes rather than ones we are effectively self-sufficient in. The Chinese are playing chess in commodities markets; we had better stop playing checkers. Our future security depends on it.

Heather Exner-Pirot is director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.