This article originally appeared in the Hub.

By Fen Osler Hampson and Tim Sargent, September 17, 2024

It was an uncharacteristically busy summer on the defence spending file. Not only did Canada face growing calls from allies at home and abroad in the runup to the July NATO Summit in Washington, D.C (including from Mike Johnson, the U.S. speaker of the House of Representatives, who labelled our lack of defence spending as “shameful”) to boost its military spending, but the Trudeau government made a surprise announcement there on the last day of the summit that it would indeed reach the 2 percent spending target by 2032.

The announcement was met with widespread skepticism. There were few details and even less evidence of follow-through. Call it “fire and forget.” This week’s return of the House of Commons will be the first opportunity for parliamentarians to question the government about its plan, including the details glaringly absent in Trudeau’s hasty announcement.

Although such a plan will be complex—including the mix of operations and capital, the role of procurement, etc.—, the fundamental question of how the federal government can fulfill its promise to boost defence spending is relatively straightforward. It starts with properly defining how Ottawa understands its core constitutional and fiscal responsibilities. To riff off James Carville’s advice to Bill Clinton during the 1992 U.S. presidential election campaign, “It’s all in the Constitution, stupid!”

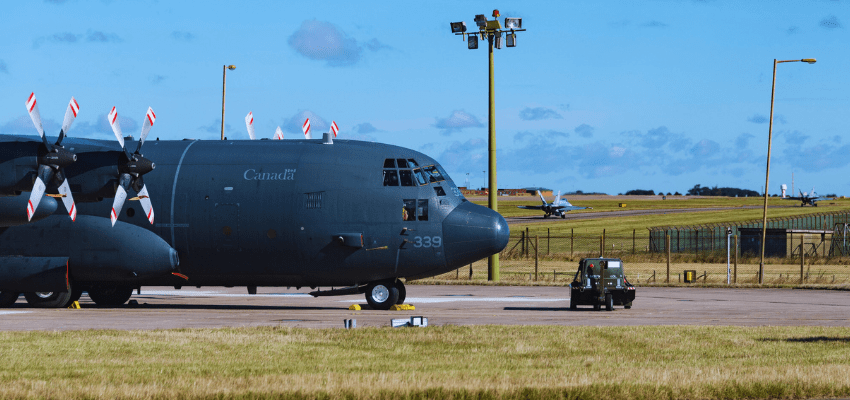

To be sure, we also need a healthy and constructive debate about what Canada should spend its money on to achieve the NATO target of two percent of GDP, whether it is to devote more resources to defending the Arctic, recruit more personnel, deal with cyberwarfare, or buy new kit such as submarines, standoff weapons, surface ships or airplanes.

However, whatever plans and programs are ultimately decided, they will only be realized if Ottawa gets back into its lane and focuses on its core responsibilities as laid out in the Canadian Constitution, which includes taking its mandate for defence and foreign affairs seriously. It will also mean that Ottawa will have to shed those programs (some of which are very costly) that are not part of or central to its constitutional mandate.

Our leaders will also have to dial down the rhetoric. Surprise announcements devoid of details of the kind the prime minister delivered at the 2024 NATO summit will further erode Canada’s credibility with its alliance partners and contribute to public cynicism.

The current constraints on the public purse are pressing and real. Absent renewed clarity about Ottawa’s formal constitutional responsibilities, politicians and bureaucrats will continue to struggle, fumble, and ultimately stumble in their efforts to promote the security and defence of the nation and reach NATO’s target.

The federal budget for fiscal year 2024-25 is $537.6 billion.

That may sound like a lot of money, but little wiggle room exists. Almost half of the budget is earmarked either for fixed transfer payments to the provinces—established by a complex formula based on provincial differences in per capita revenues, revenue sources, and tax rates—or social programs such as Old Age Security, Canada Pension Plan, and Employment Insurance, which many Canadians rely on.

Canada’s public debt now accounts for 41.9 percent of the country’s GDP, with annual interest charges totalling a stunning $54.1 billion. To put that in perspective, Ottawa now spends more on servicing its debt than its health transfers to the provinces, or more than twice what it spends on defence ($28.8 billion).

Another 19 percent of the budget is accounted for by what in Ottawa-speak is called “grants and contributions”—essentially cheques that Ottawa cuts to businesses, organizations, and people. This includes things like subsidies to battery plants, payments to First Nations, and the new dental and drug programs.

This leaves $123.1 billion—or less than a quarter of the federal budget—for all of the operating and capital expenditures of some 129 federal departments and agencies. The Department of National Defence has to compete with all these departments and agencies for new funding.

The government’s much-awaited defence policy update, released in April, pledged to increase defence spending to 1.76 percent of GDP by 2030. It included new capital equipment investments totalling $8.1 billion over the next five years, which is still far short of the $75.3 billion additional spending that the Parliamentary budget officer estimated several years ago would be required to meet the two percent benchmark by the end of the decade. Indeed, in its most recent update, the PBO estimated that “military expenditures will rise from 1.29 percent of GDP in 2024-25 to a peak of 1.49 percent of GDP in 2025-26 before falling and stabilizing at 1.42 percent by 2029-30.”

Ottawa is now engaged in some belt-tightening to meet its fiscal obligations. In its 2023-24 budget, the government also announced it is committed to reducing “the pace and scale and growth of government spending” to pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, it is leaving no stone unturned to raise revenues with higher taxes, including the recent increase in capital gains taxation.

The writing is clearly on the wall. There will be less money—not more—in the next several years to fund new programs, not to mention expenditures that are already planned.

Unless the government is willing to debt finance a significant new increase in defence, there won’t be enough money to reach 2 percent in 2032 or likely even the more modest targets in the defence update.

Raising taxes is not an option. As many economists have pointed out, taxes are already too high and are stifling Canada’s economic growth and productivity.

Of course, the irony is that Canadians, who have long been lukewarm about their military as Canada reaped the post-Cold War peace dividend, now support significant increases in defence spending. Canada’s premiers also know that Canada’s trade relations with the United States may be jeopardized if we don’t up our game on defence.

The nub of the problem is that Ottawa can only reach the 2 percent target by shedding some of its programs, including its new housing, daycare, dental benefits, national school food, and pharmacare programs. As some of Canada’s provincial premiers rightly complained, these programs fall outside Ottawa’s constitutional orbit.

That does not mean such programs should be abolished. Still, the responsibility for managing and funding these programs should devolve to the provinces where constitutional authority and political accountability ultimately reside. Such a devolution could involve ceding tax points to the provinces to fund those programs as part of the bargain.

But the dollars “saved” from doing so will likely still not be enough. Accordingly, the government should also look carefully at its other programs to see which can be cut or transferred to the provinces to achieve efficiencies and reduce delivery costs.

The debate about spending more on Canada’s defence is sometimes presented (wrongly, we believe) as a stark choice between “guns” (defence) versus “butter” (social welfare), where the challenge is to persuade Canadians and their political leaders to tighten their belts because they are living in a more dangerous world.

However, the choices are not quite so stark. Instead, Ottawa must get back into its constitutional lane and let the provinces “make butter,” while it gets serious about executing its constitutional responsibility to defend the nation.

Fen Osler Hampson is the Chancellor’s Professor & Professor of International Affairs, Carleton University.

Tim Sargent is a CIGI Distinguished Fellow and former Deputy Minister of International Trade and former Associate Deputy Minister of Finance.